Paul Revere's Ride (48 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

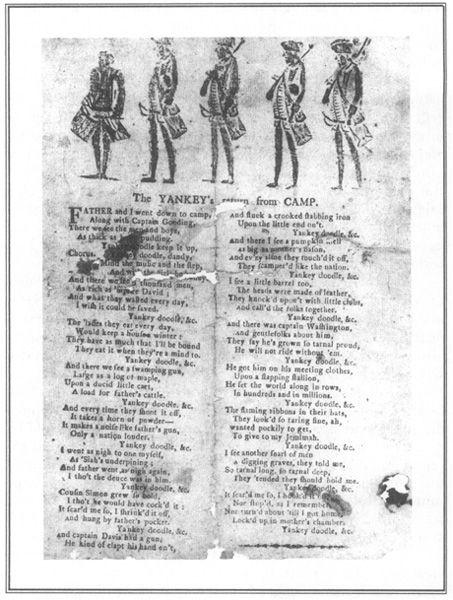

“The Yankey’s Return from Camp” was also called “The Lexington March” after the battle. Like most 18th-century American songs, it borrowed a British tune and developed it in many different forms. This early version, published in 1775, has the same modal rhythm as the tune we know as “Yankee Doodle.” American Antiquarian Society.

This second battle of Lexington and Concord was waged not with bayonets but broadsides, not with muskets but depositions, newspapers and sermons. In strictly military terms, the fighting on April 19 was a minor reverse for British arms, and a small success for the New England militia. But the ensuing contest for popular opinion was an epic disaster for the British government, and a triumph for American Whigs. In every region of British America, attitudes were truly transformed by the news of this event.

Before the battle, John Adams had been toiling on a reasoned appeal to the rights of Englishmen, which he published under the significant pen name of

Novanglus.

Later he remembered that the news of Lexington put a sudden end to that project, and instantly “changed the instruments of War from the pen to the sword.” John Adams was not a man of violence. He was genuinely shocked by news of the fighting, and deeply troubled by the question of how it began. Immediately after the battle, he saddled his horse and went off to find out for himself, traveling “along the scene of the action for many miles.” He picked his way past burial parties and burned-out houses, through crowds of refugees with cartloads of household goods, and marching soldiers with their drums and guns. Everywhere he found “great confusion and distress.” It was only a trip of a few miles from Braintree to Lexington, but John Adams later remembered it as one of the great intellectual journeys of his life. He wrote that he “enquired of the inhabitants the circumstances” of the fight, wanting to be sure about what had happened. Later he testified that his inquiries “convinced me that the Die was cast, the Rubicon crossed.” John Adams returned from Lexington, went on to the second Continental Congress, and never looked back.

60

In Pennsylvania, the news from Lexington had a similar effect on an English immigrant who had arrived only the year before. At the age of thirty-seven, Thomas Paine had lost everything in England:

his home, two wives, and many jobs. He decided to start again in America, and with the help of a letter from Benjamin Franklin, he found employment in Philadelphia as editor of the

Pennsylvania Magazine.

Suddenly things began to go better for him. Circulation leaped from 600 to 1500 subscribers. Paine threw himself into his work and kept clear of politics. He wrote later that he regarded the Imperial dispute as merely “a kind of law-suit” which “the parties would find a way either to decide or settle.” Then the news of Lexington arrived. Paine remembered that “the country into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears.” Afterward he recalled, “No man was a warmer wisher for a reconciliation than myself, before the fatal nineteenth of April, 1775, but the moment the event of that day was known, I rejected the hardened, sullen-tempered Pharaoh of England forever.”

61

In Virginia, April was the planting time in the Potomac valley. The countryside was in bloom, and the air was soft with the scent of Spring. George Washington was working happily on his farm at Mount Vernon when the first report of Lexington arrived. Like many thousands of Americans, he left his fields and gathered up his weapons with a sadness that was widely shared in the colonies. To a close friend he wrote, “Unhappy it is, though, to reflect that a brother’s sword has been sheathed in a brother’s breast and that the once-happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with blood or inhabited by a race of slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice?”

62

Many men, virtuous or not, faced that same choice throughout the colonies. The battles of Lexington and Concord posed it for them in a new way. Long afterward, the novelist Henry James visited the Old North Bridge, and looked back upon that moment of decision. He wrote, “The fight had been the hinge—so one saw it—on which the large revolving future was to turn.”

63

The Fate of the Participants

The Fate of the Participants

It seemed as if the war not only required but created talents.”

—David Ramsay, 1793

THE COST turned out to be very high—higher perhaps than our generation would be willing to pay. On both sides, many of the men who fought at Lexington and Concord died in the long and bitter war that followed. In the British infantry, few of the anonymous “other ranks” who marched to Concord survived the conflict unscathed. Many would be dead within two months.

At the battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, General Gage again used his ten senior companies of grenadiers and light infantry as a

corps d’elite.

They suffered grievously. The grenadier company of the Royal Welch Fusiliers went into that action with three officers, five noncoms, and thirty other ranks. It came out with one corporal and eleven privates. The light infantry company of the same regiment also lost most of its men—so many that it was said, “the Fusiliers had hardly men enough left to saddle their goat.”

1

Other regiments suffered even more severely. The grenadier company of the King’s Own counted forty-three officers and men present before the battle of Lexington and Concord. Only twelve of that number were still listed as “effective” after Bunker Hill. Most of the flank companies in General Gage’s army also experienced heavy losses.

2

Altogether, seventy-four British officers had marched to Lexington

and Concord. Of that number, at least thirty-three were killed or severely wounded between April and June in the lighting around Boston. Others suffered minor wounds that were not thought to be disabling.

Major John Pitcairn, the commander at Lexington, died of wounds received at Bunker Hill. As he rallied his Marines for a third assault on the American redoubt, he was shot in the head by another veteran of April 19, an African-American militiaman named Salem Prince. Major Pitcairn was carried off the field by his own son, an officer in the same battalion, and died in Boston. His death was mourned even by his enemies, who called him “a good man in a bad cause.” After the war his family asked that his remains should be returned for burial in London. According to an old Boston tradition, the wrong body was sent by mistake, and Major Pitcairn may still lie in the blue clay of Boston, or perhaps in a vault beneath the Old North Church.

3

Also at Bunker Hill was Lieutenant Jesse Adair, the hard-charging young Irish Marine who had volunteered to lead the British vanguard to Lexington, and sent it headlong into Parker’s militia. At Bunker Hill he volunteered again to lead the assault, though he was not supposed to be there at all, and miraculously survived. On the day the British army left Boston he volunteered once more to command its rear guard. His orders were to slow the American advance by scattering in its path a thick carpet of caltrops, or crow’s feet, small iron devices shaped like a child’s jack, with needle-sharp spines that could cripple a man or horse. Lieutenant Adair behaved in his usual style, brave and brainless as ever. An English officer remembered that “being an Irishman, he began scattering the crow-feet about from the gate towards the enemy, and of course had to walk over them on his return, which detained him so long that he was nearly taken prisoner.” Adair was later promoted to captain, and rose to command Number 45 Company of the Royal Marines, in the Plymouth Division. He served throughout the American war, but was not the sort of officer who flourished in peace. In 1785 Captain Adair was “reduced,” and disappeared from the Marine List.

4

Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Smith, who several junior British officers held personally responsible for their troubles at Lexington and Concord, was highly praised in dispatches by General Gage. Afterward he was promoted to brigadier. At the siege of Boston, Francis Smith’s men brought him early notice of the American occupation of Dorchester Heights. He is reported to have done

nothing, not even bothering to notify his commander of an event that made Boston untenable for the British garrison and forced them to evacuate the town. In the next campaign, at New York City, Smith commanded a brigade. At a critical moment Lieutenant Mackenzie, the able adjutant of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, showed him a way to cut off Washington’s retreat. Mackenzie later wrote that the brigadier was not only “slow,” but also seemed “more intent on looking out for quarters for himself than preventing the retreat.” Afterwards he was promoted again, to the rank of major-general. Historian Allen French observes, perhaps a little harshly, that Francis Smith deserves more credit than he commonly receives, for singlehandedly “losing the American War.”

5

Lord Hugh Percy also fought at New York, with the same skill and courage that he had shown on the retreat from Lexington. He was instrumental in the capture of Fort Washington, the largest surrender of American troops up to that moment, and was promoted to Lieutenant General. But he grew so disgusted with the conduct of the war that he resigned his command and returned to Britain in 1777. Later he inherited the title of Duke of Northumberland. In his mature years he became one of the richest men in England, and also (it was said) one of the most irascible. His ill-temper was attributed to gout; perhaps his experiences in America also played a role. Percy died on July 10, 1817.

Several junior British officers who served at Concord survived the war and rose to high command. In 1775, George Harris was captain of grenadiers at Lexington and Concord. He was severely wounded in the head at Bunker Hill as he led the final assult on the American redoubt. Four of his grenadiers tried to carry him to safety, and three were shot. Harris cried out, “For God’s sake let me die in peace.” His men succeeded in rescuing him, and he was taken to Boston where a surgeon trepanned his skull while Harris stoically observed the operation by way of a mirror. He survived, returned to duty by 1776, fought in every major battle except Germantown, was severely wounded yet again, saw heavy campaigning in the West Indies, survived a major action at sea, was captured by a French privateer, and shipwrecked on his way to Ireland in 1780. When offered another command in America, he resigned his commission. Later he was persuaded to accept a command in India, where he played so large a part that he was raised to the peerage as Baron Harris of Seringapatam, Mysore, and Belmont in Kent. He died in 1829.

Captain Harris’s able subaltern in the grenadiers of the 5th

Foot, Lord Francis Rawdon, survived Bunker Hill with two bullets through his cap. In later actions he rose rapidly to high command, with a record of brilliance and cruelty in the southern campaigns of the American War. In 1783 he was raised to the peerage, promoted to major-general ten years later, and succeeded his father as second Earl of Moira. In 1812 he became British commander in chief in India and governor-general of Bengal.

Another survivor was Ensign Martin Hunter of the 52 nd Foot. He served with honor through the American war, commanded his regiment in India, rose to high rank in the Napoleonic wars, married a Scottish heiress, retired as General Sir Martin Hunter, and died full of honors in 1846, probably the last living British officer who had served at Lexington and Concord.

6

In the Royal Navy, Admiral Samuel Graves continued to rage against the Americans with such undiscriminating fury that after the battles of Lexington and Concord he even had a fistfight with a Loyalist in the streets of Boston. Graves ordered his captains to burn every seaport north of Boston, and the town of Falmouth in Maine was actually destroyed in that way. The burning of Falmouth caused high outrage in America and Britain. Graves was relieved of command in January 1776 and ordered home. He was offered a face-saving assignment ashore, but refused it and died in retirement in 1787.