Paul Revere's Ride (41 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

This armigerous Horatio Alger rebuilt the Percy family’s ruined castles, revived its wasted fortunes, restored its vast estates, planted 20,000 trees in its handsome parks, and developed large deposits of coal on ducal lands into a major source of energy for the industrial revolution. (By the 19th century, the estates of the Duke of Northumberland would yield the fifth largest landed income in England.)

7

All this was the patrimony of Brigadier Lord Hugh Percy, who was heir to one of the great fortunes in the Western world. At the same time, he was also a highly skilled professional soldier, with military experience far beyond his thirty-two years. Percy was

gazetted ensign at the age of sixteen, earned his spurs at the battles of Bergen and Minden, became a lieutenant-colonel at nineteen, and aide-de-camp to King George III at the age of twenty-three. Like his father he married advantageously—to the daughter of the King’s mentor Lord Bute. When his father was given a dukedom, he gained the courtesy title of Earl Percy, and was also elected to a seat in the British House of Commons.

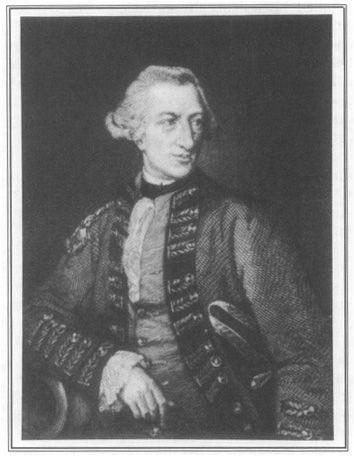

Lord Hugh Percy, thirty-two years old, was the eldest son of the Duke of Northumberland, and colonel of the 5th Foot (later named the Northumberland Fusiliers). He commanded the brigade that marched to the relief of the British Concord expedition. (Author’s Collection)

In 1774 Lord Percy came to Boston as colonel of his own regiment, the 5th Foot, later to be known as the Northumberland Fusiliers. He was not much to look at. Like many of his officers and men, Percy was in chronically poor health. He was a sickly, wasted figure with a thin and bony frame, hollow cheeks, a large protruding

nose, receding forehead, and eyes so dim that he was unable to read by candlelight. His body was beginning to be racked by a hereditary gout.

8

But in colonial Boston he cut a great swath. Lord Percy rented a large house that had once been the residence of the Royal Governor. He bought what he took to be the best riding horse in New England for the princely sum of £450, and imported a matched pair of carriage horses when none of the local stock pleased him. In his dining room he lavishly entertained his brother officers, and made many friends in the garrison and the town. “I always have a table of twelve covers set every day,” he wrote home.

9

Throughout the army he was immensely popular. In an age of deference, many Englishmen deemed it an honor to be commanded by the eldest son of a Duke—a gallant young gentleman who perfectly personified the virtues of his class. He was honorable and brave, candid and decent, impeccably mannered, and immensely generous with his wealth. When his regiment came to Boston, Lord Percy chartered a ship at his own expense to bring over the wives and children. On another campaign he gave every man in the regiment a new blanket and a golden guinea out of his own pocket. He detested corporal punishment. At a time when other commanders were resorting to floggings and firing squads on Boston Common, he led his regiment by precept and example. When his men went on long marches, Lord Percy left his horse behind and made a point of marching beside them, gout and all. His mother wrote him in 1770, “I admire you for marching with your regiment; I dare say you are the only man of your rank who performed such a journey on foot.”

10

Lord Percy came to America with a strong sense of sympathy for the colonists. Like many high aristocrats in 18th-century England, he was a staunch Whig. In Parliament he had voted against the Stamp Act, and regarded Lord North’s American policy as a piece of consummate folly. He had no wish to fight Americans. “Nothing less than the total loss or conquest of the colonies must be the end of it,” he wrote, “either, indeed is disagreeable.”

11

But once in Boston, Lord Percy began to change his mind. He was appalled by what he took to be the narrowness of New England ways, and genuinely shocked by the mobbings that he witnessed in Massachusetts. His outrage was not that of a modern liberal, but of an 18th-century gentleman who came to regard the people of Boston as a race of money-grubbing hypocritical bullies and cowards, utterly devoid of honor, candor, and courage.

“Like all other cowards,” he wrote, “they are cruel and tyrannical.”

12

Percy came to believe that the inhabitants of New England were “the most designing artful villains in the world.” He thought that they had “not the least idea of religion or morality.”

13

In particular he detested the Congregational clergy for denying their churches to Loyalists, and despised the Yankee town meetings for their interminable debates. “The people here,” he wrote home, “talk much and do little.” He thought that the men of New England were incapable of action, and utterly contemptible as a military force. “I cannot but despise them completely,” he wrote. On the morning of April 19, 1775, the American education of Lord Percy was about to begin.

14

The 1st Brigade finally marched at about 8:45. It made a brave sight as it left the little town with music playing and colors flying. In the lead was its commander, Lord Percy himself, splendidly mounted on his handsome sorrel horse, and resplendent in a uniform of scarlet and gosling green with trimmings of silver lace.

Behind him came three regiments of British infantry. Pride of place went to the 4th (King’s Own) Foot, proudly bearing the monarch’s cipher on its colors, and the dark blue facings of a Royal regiment on its faded red tunics. Nobody trifled with the King’s Own. Even their nickname in the army connoted high respect. They were called the Lions after their badge, which was the lion rampant of England. That emblem had been awarded for gallantry by William III and was proudly embroidered on all four corners of their regimental colors. In 1773, an inspector described the King’s Own as “a very fine body of men, well dressed and fit.” As it marched from Boston, an expert observer would have noticed that it was also exceptionally well equipped. The 4th had recently been rearmed with a new musket, two inches shorter and two pounds lighter than the previous issue, and so closely bored to the caliber of its ammunition that the regiment was among the first in Gage’s army to be issued steel ramrods.

15

Next in Percy’s brigade came the 47th Foot, unkindly nicknamed the Cauliflowers for their uncommon off-white facings, but highly respected as a fighting regiment. The 47th had brilliantly distinguished itself in the conquest of Quebec, and gloried in the name of “Wolfe’s Own.” The entire army sang a drinking song called “Hot Stuff,” to the tune of “The Lilies of France,” that celebrated its valor:

Come each death-doing dog who dares venture his neck,

Come, follow the hero that goes to Quebec…

And ye that love fighting shall soon have enough:

Wolfe commands us, my boys; we shall give them Hot Stuff…

When the forty-seventh regiment is dashing ashore,

While bullets are whistling and cannons do roar.

16

Percy’s brigade also included one of the most colorful regiments in the army, the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers,

17

renowned equally for its steady courage and strange customs. Every St. David’s Day (March 1) its new subalterns were compelled to stand with one foot on a chair and the other on a mess table and swallow a raw leek without flinching, while the regimental drummers beat a solemn roll. On parade, these men marched proudly behind their mascot, a snow white goat with gilded horns from the Royal herd at Windsor, a custom described as “ancient” as early as 1775. The regiment gloried in its nickname of the Nanny Goats.

18

For all its quaint folkways, it was a highly professional unit that had served with distinction at Namur, Blenheim, Ramillies, Oude-narde, Malplaquet, Minden, and many other fields. At Dettingen in 1743 the regiment was commanded by George II, the last British king to lead an army into battle. For its courage the 23rd was allowed to wear the White Horse of Hanover on its colors.

19

When the Royal Welch Fusiliers arrived in America, General Haldimand sent a glowing report in his native French to General Gage: “Je dois en Justice informer votre Excellence que les Fusiliers se sont tres bien conduit ici. Ce corps est bien composé et tres bien commandé.” General Gage replied, “I dare say the Fusiliers will deserve the character you give of them. They were always esteemed a good corps and have gained reputation wherever they served.”

20

Also in the column was Lord Percy’s largest unit, a reinforced battalion of British Marines, the seagoing policemen of the Royal Navy, in brilliant red and blue uniforms with snow-white facings of a distinctive nautical cut. The men of the Marine battalion tended to be smaller in stature than those in the army. Their commander, Major Pitcairn, wrote home to a friend, “I am mortified to find our Marines so much shorter than the marching regiments. I wish you could persuade Lord Sandwich to give an order not to enlist any man under five feet six.” But these men had a fearsome reputation as fighters, in combat and out. They marched behind their drums with a distinctive rolling swagger that marked them as a breed apart from the army.

21

Interspersed between the long red columns of British infantry

were the dark blue tunics of the Royal Artillery. Their regimental motto was

Ubique,

the same as the Royal Engineers. The Gunners insisted that their

Ubique

meant “Everywhere,” while the slogan of the Sappers should be translated “All over the Place.” In any case, here they were again, marching beside two stout six-pounder field guns, with long trails and massive wooden wheels that rumbled ominously through the streets of Boston.

22

Also traveling with the brigade were armed New England Loyalists in civilian dress, who have rarely been noticed in American histories of the battles. These American Tories were angry men, hungry for revenge against the “Rebels” who cruelly tormented them. Some were employed as mounted scouts. Prominent on horseback at the head of the column was a Boston Tory named George Leonard. Others marched behind the infantry as civilian auxiliaries. One of their number was a Tory barber named Warden, who hated the Whigs of New England so passionately that he shouldered a musket and joined the brigade as a volunteer.

23

The British soldiers were in a merry mood as they left town. No serious trouble was expected from the “country people,” or at least nothing that these proud regiments would not be able to handle. Their fifes and drums played a spirited version of “Yankee Doodle” as a taunt to the inhabitants—a musical joke that would long be remembered in Massachusetts. Afterward, a London wit suggested that a more suitable song might have been “The Ballad of Chevy Chase”:

To drive the deer with hound and horn

Earl Percy took his way.

The child may rue that is unborn

The hunting of that day!

24

The brigade marched south across Boston Neck, then west through the villages of Roxbury and Brookline, and north at the present site of Brighton to the Great Bridge over the Charles River. The long red column crossed into Cambridge, and wound its way past the austere brick buildings of Harvard College.

The towns along the route were normally teeming with activity at that hour, but this morning they appeared to be deserted. “All of the houses were shut up,” Percy wrote, “and there was not the appearance of a single inhabitant. I could get no intelligence concerning them

[sic]

till I had passed Menotomy.”

25

One of the few people he met was Isaac Smith, an absentminded

Harvard tutor who had the misfortune to emerge from the College just as the brigade was passing. Percy asked the way to Lexington. Without thinking, Smith told him. Those who knew Tutor Smith believed that he did not intend to aid the enemy, but was merely oblivious to the larger world. Even so, the people of Cambridge were not amused. They were so displeased that Isaac Smith “shortly afterwards left the country for a while.”

26

With the help of directions from the distracted Harvard tutor, Percy found the road to Lexington. Still he knew nothing of what had happened to Colonel Smith’s force, or what lay ahead for his own brigade. Not until he reached Menotomy at about one o’clock in the afternoon did he learn of the fighting on Lexington Green. A little further, he met a chaise coming toward him in the road. In it was Lieutenant Edward Gould of the King’s Own, who had been wounded in the foot at Concord Bridge. Gould told Lord Percy that the grenadiers and light infantry had been “attacked by the rebels about daybreak, and were retiring, having expended most of their ammunition.”

27

Percy sent the wounded officer on his way and began to study the countryside with growing concern. A casual tourist might have taken pleasure in its rolling woods and fields, dotted with granite outcroppings and lined with picturesque stone “fences.” But to the trained eye of a professional soldier, the terrain took on a more sinister appearance. “The whole country we had to retire through,” Percy wrote, “was covered with stone walls, and was besides a very hilly stony country.” Many other officers were also looking nervously about them. Lieutenant Barker of the King’s Own noted that “the country was an amazing strong one, full of hills, woods, stone walls, etc.”

28