Paul Revere's Ride (19 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

At the Newman House, on the corner of Salem and Sheafe streets, Paul Reveremet Robert Newman and John Pulling and asked them to hang the lanterns in the Old North Church. The building was a boarding house in 1575, occupied by British offficers. The storefront was a later addition. The building no longer stands. This old photograph by Wilfred French is in the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

Then they went to a narrow ladder above the stairs and climbed higher, rung after rung, past the open beams and great silent bells. At last they reached the topmost window in the steeple. They threw open the sash, and held the two lanterns out of the northwest window in the direction of Charlestown.

29

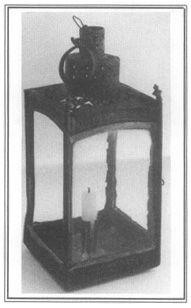

The Old North Church from Hull Street, from an old photograph. To the left is Copp’s Hill burying ground. To the right are houses that were occupied by British troops in 1775. The steeple window showing here faces north toward Charlestown. From it Newman and Pulling displayed two lanterns, one of which survives today in the Concord Museum. (Bostonian Society)

Across the river, the Charlestown Whigs were keeping careful watch on the steeple. In the night it appeared to them as a slim black spire, silhouetted against the starry southern sky. Suddenly they saw a flicker, and then a flash of light. They looked again, and two faint yellow lights were burning close together high in the tower of the church. It was the signal that Revere had promised to send if British troops were leaving Boston by boat across the Back Bay to Cambridge.

The lights were visible only for a moment. Then Newman and Pulling extinguished the candles, closed the window, descended the steeple stairs, and returned the lanterns to their closet. As they prepared to leave the church, they saw a detachment of troops in the street near the door. The two men ran back into the sanctuary of the church, searching for another way out. They climbed a bench near the altar, and escaped through a window, their mission completed.

30

The men of Charlestown acted quickly on the signal. Some went down to the water’s edge to look for Paul Revere. Others hastened to find him a horse. While waiting for his arrival they dispatched their own express rider to the Committee of Safety in Cambridge. One of them wrote later, “This messenger was also instructed to ride on to Messrs Hancock and Adams who I knew were at the Rev. Mr. [Clarke’s ] at Lexington …”

31

This anonymous Charlestown courier never reached his destination. Probably he was stopped by the British officers who lay in wait on the Lexington Road. General Gage’s meticulous precautions were beginning to take effect. His roving patrols intercepted many travelers that night, and may have captured this first messenger who threatened to reveal his plans.

While the Charlestown Whigs were acting on the lantern signal, Paul Revere went to his own home in North Square, a few short blocks from the church. His family helped him to collect his heavy boots and long riding surtout. Perhaps he thought about taking his pistol, but decided to go unarmed, a decision that may have saved his life.

The time was about 10:15 when Revere left his house. Later he remembered, “I … went to the north part of the town, where I had kept a boat.” Here again, Revere enlisted another group of friends to assist him. He sought the aid of two experienced Boston watermen to help him cross the Charles River. One was Joshua Bentley, a boat builder. The other was Thomas Richardson.

32

Both men met Paul Revere by his boat, hidden beneath a wharf on the waterfront, in the North End. The folklore of old Boston cherishes many memories of that moment. It is said that Paul Revere absent-mindedly forgot his spurs and sent his faithful dog trotting home with a note pinned to his collar. A few minutes later the dog returned. The note was gone, and a pair of spurs was in its place. The reader may judge the truth of this legend.

33

Another folktale has it that as Bentley and Richardson prepared to launch the boat, they discovered that they had forgotten a cloth to muffle their oars. The two men knocked softly at a nearby house. A woman came to an upper window, and they whispered an urgent request. There was a quick rustle of petticoats in the darkness, and a set of woolen underwear came floating down to the street. The lady’s undergarments, still warm from the body that had worn them, were wrapped snugly round the oars.

34

The three men balanced themselves in Paul Revere’s little boat and pushed off into the harbor, rowing north from Boston toward Charlestown’s ferry landing. Suddenly, another danger loomed in their path. The dark bulk of HMS

Somerset

was anchored squarely in their way. Four days earlier she had been moored between Boston and Charlestown to interrupt the nocturnal traffic between the towns. At 9 o’clock that night, the ferries that plied between the towns had been seized, and secured alongside the British ship, with all “boats, mud-scows, and canoes” in town. No crossings were allowed after that hour.

35

Paul Revere looked up from his little rowboat at the great warship. She was a ship of the line, rated for 64 guns. He could expect the men of her watch to be alert, and armed sentries to be posted fore and aft. Probably he heard across the water the ship’s bell chime twice in quick succession, then twice more, and once again as the midshipman of the watch marked the time at five bells in the evening watch, or 10:30 to a landsman.

Paul Revere sat quietly in the boat while his friends bent over their muffled oars. All his senses were alive, sharpened by the danger that surrounded him. Artist that he was, in that moment of mortal peril he noticed with special intensity the haunting beauty of the scene. Many years later the memory was still fresh in his mind. “It was then young flood, the ship was winding, and the moon was rising,” he wrote in the haunting cadence of the old New England dialect. The great warship must have seemed a thing alive as she moved restlessly about her mooring, swinging slowly to the west on the incoming tide. In the fresh east wind, she pulled hard against her great hemp anchor cable that creaked and groaned like an animal in the night.

The moon was coming up behind Boston, a huge orb of light in the clear night sky. To Paul Revere it must have seemed impossible to pass the ship without detection. Then, miraculously, it was the moon that saved him. The moon was nearly full, a large pale yellow globe that was just beginning to rise in the southern sky.

Normally, Paul Revere’s boat would have been caught in the bright reflection of the moonbeam on the water as he passed close by HMS

Somerset.

But there was something odd about the moon that night. Often it rose farther to the east, but that night it had a southern declination. A lunar anomaly caused it to remain well to the south on the evening of April 18, 1775, and to hang low on the horizon, partly hidden behind the buildings of Boston. The sky was very bright, and Paul Revere’s boat was miraculously shrouded in a dark moonshadow that was all the more obscure because of the light that surrounded it. He passed safely “a little to the eastward” of the great ship’s massive bowsprit that pointed downstream toward the incoming tide.

36

Revere’s skilled boatmen set him safely ashore at Charles-town’s ferry landing. Another group of his many friends was waiting there. Later he remembered, “I met Colonel Conant, and several others; they said they had seen our signals. I told them what was acting.”

Revere talked briefly with Richard Devens, the Charlestown Whig who was a member of the Committee of Supplies. As they walked from ferry landing into the town, Devens warned him to take care on the road, and to stay alert for British officers who were patrolling the highway to Lexington. Devens added that he himself had met them earlier in the evening, “nine officers of the ministerial army, mounted on good horses, and armed, going towards Concord.” Revere listened carefully. Then, he later wrote in his laconic Yankee way, “I went to git me a horse.”

37

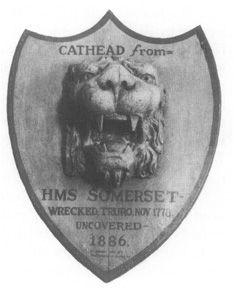

This sinister cathead embellished an anchor-boom on the bow of HMS

Somerset.

Paul Revere’s boat passed beneath it, as the great ship strained at her mooring against the incoming tide. In 1777, the cathead was salvaged from the wreck of the

Somerset

on Cape Cod, and survives today at the Pilgrim Monument and Province-town Museum.

The Charlestown Whigs had already given thought to the horse. One of the fleetest animals in town belonged to the family of John Larkin, a deacon of the Congregational church, who agreed to help. The Larkin horse was a fine great mare named Brown Beauty, according to family tradition. She was neither a racer nor a pulling animal, but an excellent specimen of a New England saddlehorse—big, strong, and very fast.

38

Many years ago, equestrian historians concluded from their research that Brown Beauty was probably the collateral descendant of an East Anglian animal, distantly related to the modern draft horse known as the “Suffolk Punch.” The horses of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, like the Puritans who rode them, came mainly from the east of England. In the new world these sturdy animals were bred with Spanish riding stock to create a distinctive American riding horse that can still be found in remote towns of rural Massachusetts. New England’s saddle horses were bred for alertness and agility on Yankee ice and granite. At their best they were (and are) superb mounts—strong, big-boned, sure-footed, and responsive. Such an animal was Deacon Larkin’s mare Brown Beauty, who was lent to Paul Revere that night.

39

The horse was led out of the Larkin barn, and handed to Paul Revere by Richard Devens. The rider took the reins, put a booted foot into the stirrup, and sprang into the saddle. He said a last word to his friends, and urged the animal forward.

Brown Beauty proved a joy to ride. “I set off upon a very good horse,” Paul Revere wrote later, “it was then about 11 o’clock, and very pleasant.” The night was mild and clear. After a long New England winter, the first welcome signs of spring were in the air. The heavy musk of damp soil and the sweet scent of new growth rose around him in the soft night air.

Paul Revere headed north across Charlestown Neck, past the grim place where the rotting remains of the slave Mark still hung in rusty chains. Then he turned west on the road to Lexington, and kicked his horse into an easy canter on the moonlit road. He always savored that moment—a feeling that any horseman will understand. Psychologists of exercise tell us that there is a third

stage of running, which brings euphoria in its train. There is also a third stage of riding, called the canter. After the tedium of the walk and the bone-jarring bounce of the trot, the animal surges forward in an easy rolling rhythm. Horse and rider become one being, more nearly so than in any other gait. The horse moves gracefully over the ground with fluent ease, and the rider experiences a feeling of completeness, serenity, and calm. Paul Revere’s language tells us that such a feeling came to him as he cantered along the Lexington Road. Even at the vortex of violent events that were swirling dangerously around him, he experienced a sensation of quiet and inner peace.

40