My Life So Far (27 page)

I got Robin’s e-mail address from Gloria Steinem, a friend, and wrote to her, telling her how important her honesty had been to me. I asked, “How is it that otherwise strong, independent women can do these things?” She answered: “You’d be surprised how many ‘otherwise strong, independent women’ have done these things.”

In my public life, I am a strong, can-do woman. How is it, then, that behind closed doors, in my most intimate relations, I could voluntarily betray myself? The answer is this: If a woman has become disembodied from a lack of self-worth

—I’m not good enough—

or from abuse, she will neglect her own voice of desire and hear only the man’s. This requires, as Robin Morgan says, compartmentalizing—disconnecting head and heart, body and soul. Overlay her silence with a man’s sense of entitlement and inability (or unwillingness) to read his partner’s subtle body signals, and you have the makings of a very angry woman, who will stuff her anger for the same reasons she silences her sexual voice.

V

adim was the first man I had ever loved, and in spite of the complexities (and in some part because of them), the love was real enough that for a long time my anger was only a background whisper. I loved that he was like a kaleidoscope and I could see the world through all his different prisms. He helped me rediscover my sexuality (and that of other women in the process), gave me an if-he-loves-me-I-must-be-okay kind of confidence, and helped move me out from under my father’s shadow. I had a persona now. I was with a “real man,” I ran his house, was a good stepmother to his daughter and to his son, Christian, when Catherine Deneuve agreed to let him visit us. Vadim’s friends seemed to like me. What wasn’t to like? I never complained, rarely scolded, worked hard, brought in the money, brought them their whiskeys at night, and made them their breakfast in the morning when they were hungover, and they knew I participated with Vadim in his sexual libertinism. I remember one of the group remarking, as I was leaving with a tray of glasses to be refilled, “Jane is something else, not like most women, more like one of us.” I fairly purred with pleasure, as I had at age ten when someone had asked if I was a boy or a girl.

Unlike the magician’s assistant in the poem at the start of this chapter, my functioning self did not know what was real, that there was another way to be, a “secret kingdom” of the embodied self that I could be Abracadabred to, authentic and whole. I had long since abandoned that self. I so needed to

not

know, in order to remain in the relationship. I transformed myself with Vadim’s magic wand into the perfect sixties wife. I didn’t need his money, so it wasn’t an economic issue. It was the fear of losing the relationship, since it was the relationship that validated me. If someone had asked me to describe who I was then, I would have had a difficult time of it. But as film critic Philip Lopate once wrote: “Where identity is not fixed, performance becomes a floating anchor.” And could I perform! Making the unreal seem real, the sad seem happy, hoping that somewhere along the way it would all work out, that I would discover who I was. Meantime I had an anchor.

I would often talk to Vadim about my insecurities, but he didn’t really understand, though he tried in his own way to give me confidence. The problem was, he knew how to validate only my façade, and the façade worked so well that there seemed no pressing need to go deeper. “Deeper” might have meant my becoming more assertive, more opinionated, more who I was, and as Vadim said publicly (later, after I’d left him and become more . . . me), he liked his women “softer.” At that time, if it was soft he wanted, I’d give him squooshy.

I made a list one day of what I considered my main faults: selfishness, stinginess, and being too judgmental were the top three. Then and there I decided that if I pretended to be generous and forgiving for a long enough time, maybe I would become those things. I remembered reading Aristotle in philosophy class at Vassar: “We become just by performing just actions, temperate by performing temperate actions, brave by performing brave actions.” I had always felt that you become what you do—which is one reason I fretted so when I was asked to play silly young women like my characters in

Tall Story

and

Any Wednesday.

If you behave one-dimensionally day after day, you start to become one-dimensional, and after a while the ability to reach deeper becomes atrophied.

Y

ou could say that Vadim majored in vacations. His love of certain natural environments and talent for enjoying them was unbounded, and I was a beneficiary. He loved the sea and its shores. We would go not just to glamorous Saint Tropez, but to the rugged coast of Brittany on the Atlantic in the northern region of France and to the Bay of Arcachon on the southern Atlantic coast. We would pile into an outboard motorboat with Nathalie, Christian, and

grande

Nathalie (daughter of Vadim’s sister, Helene) and go for picnics on some of the sand dunes that would emerge at low tide.

Grande

Nathalie was almost ten years older than

petite

Nathalie and often accompanied us on our vacations.

Beached in Arcachon, France, with Nathalie (in the boat with me) and Christian watching.

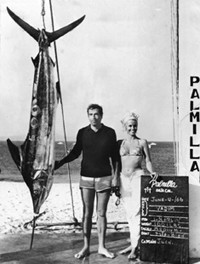

Vadim and me in Baja California on one of our many deep-sea-fishing trips.

Petite

Nathalie was growing into a beautiful combination of her Danish mother and Franco-Slavic father, the same exotic eyes and dark hair, with legs that went on forever. She was a challenging child. Her stubbornness and moodiness were evident; she kept her deeper self tucked away, and I never really knew what she felt—except for her love for her father. She and I were always battling over issues like brushing her teeth and doing her lessons, and I suspected she thought I was a nag. (Forty years later, she remains a member of my family.)

Often Vadim and I would go to Saint Tropez in the winter, my favorite time there. We’d stay in a small, not fancy hotel/restaurant called Tahiti Hôtel, right on Pampelonne Beach, the one that became famous for its nude sunbathers in summertime (which is one reason I preferred winter). I loved the Mediterranean storms—the mistrals—that would bend the palm trees and send waves high onto the beach. Vadim and I would sit by a cozy fire, playing chess and watching nature rage.

Next to the sea, Vadim loved mountains best. He was an excellent skier and we often spent Christmas in Megève or Chamonix, two ski resorts in the French Alps. But just as I preferred Saint Tropez in the winter, I loved most when we would go to Chamonix in the summer. We’d always drive from Paris to the mountains with Nathalie, singing French songs and playing road games. We would rent a chalet in the little town of Argentière, adjacent to Chamonix, in the valley of the Mont Blanc.

It would be sunny, the air pure and brisk, the wildflowers just emerging. The sparkling, majestic Alps rose sharply on both sides of the valley, with Mont Blanc to the south lording it over them all. From time to time, an awesome rumble would echo down the valley as melting snow avalanched from the peaks. Once, at night, I saw the northern lights dancing in the sky, and sometimes, when the sun was at just the right angle, I could spy the faint blue of the glaciers. I took long walks along the creeks, watched the Lenten roses as they blushed open, and thought how I had never been happier in my life, so happy my heart felt like bursting. I learned that spring that I am molecularly suited to high altitudes. Fourteen thousand feet is as high as I’ve ever hiked, but up there where the air is thin and crisp and the tundra spongy, I feel transcendent.

On one of these alpine vacations, Vadim left me to go to Rome to fetch his baby son, Christian. I didn’t know until I read Vadim’s book

Bardot, Deneuve, Fonda

that he had had a passionate night with Catherine and that he thought “everything would work out with [her], that [his] relationship with [me] was only a dream, and that Christian would grow up living with a mother and father who loved each other.” Reading that so many years later didn’t hurt me, but I wondered how I could have been so naïve as to think his commitment to me was real.

I had no experience with the care and handling of infants, but I threw myself into it with enthusiasm when Vadim brought the baby to our chalet that spring. He was truly a hands-on father, comfortable with bottles and diapers. I remember Christian, Nathalie, and me taking our baths together in a tub much too small to accommodate us all. I didn’t feel totally sure of myself as a stepmother, but I liked being with the children and having a family. Susan was never far from my heart at those times.

T

here are certain things you are not supposed to do if you are just becoming a star and want to survive in Hollywood. You don’t go and live in an attic with a French director and refuse to come back unless you absolutely have to. But I never followed career rules. For better or worse, I didn’t think of myself as a movie star with a real career. I was never fully vested in my celebrity. I felt I’d gotten into it by default, and I wouldn’t die if I got out of it by default. I liked the work, the structure it gave my life, the challenges of different roles, and the pleasure I would sometimes derive from bringing a character to life. I also liked being financially independent. But the choices I made in relation to work were always connected to my relationships or, later, my politics.

In late spring I was offered the title role in

Cat Ballou

with Lee Marvin. It meant returning to Hollywood, but Vadim encouraged me to take it, saying he would come visit whenever he could. For reasons I don’t recall, I was under a contract to Columbia Pictures, where

Cat Ballou

was to be made, and this was a way to fulfill part of it. The script was unusual, and I wasn’t sure whether it was any good or not. I’m not sure Lee Marvin knew either. I remember him whispering to me one day during rehearsal that the only reason he and I were in the movie was that “we’re under contract and they can get us cheap.”

Cat Ballou

was a relatively low-budget undertaking. It seemed we’d never do two takes unless the camera broke down. The producers had us working overtime day after day, until one morning Lee Marvin took me aside.

“Jane,” he said, “we are the stars of this movie. If we let the producers walk all over us, if we don’t stand up for ourselves, you know who suffers most? The crew. The guys who don’t have the power we do to say, ‘Shit, no, we’re workin’ too hard.’ You have to get some backbone, girl. Learn to say no when they ask you to keep working.”

I will always remember Lee for that important lesson. At least I was learning to say no in my

professional

life.

I have to admit, it wasn’t until I saw the final cut of

Cat Ballou

that I realized we had a hit on our hands. I hadn’t been around when they filmed Lee’s horse, leaning cross-legged up against the barn in what’s become a classic image, or the scenes when Lee tries to shoot the side of the barn. I didn’t realize how director Elliot Silverstein would use the two troubadours, Nat “King” Cole and Stubby Kaye, like a Greek chorus. It would be my first genuine hit, though its success had very little to do with me. By the way, Nat “King” Cole was every bit as kind and wonderful as I had remembered him from my parents’ parties after the war.

During the filming of

Cat Ballou

and the movie I did right afterward for Columbia,

The Chase,

Vadim, Nathalie, and I lived in a rented house in Malibu Colony, right on the beach. Like my father, Vadim loved to fish and would often do so from the shore, pulling in perch and sometimes halibut, which we’d have for dinner. Today, of course, you wouldn’t dare eat fish from Santa Monica Bay even if you did manage to catch one, which is unlikely. The house we rented had belonged to Merle Oberon and was bright and cozy. We paid $200 a month for it, and I remember how astounded I was when the rent went up to $500.

What could they be thinking!

Today a house like that rents for closer to $10,000 a month or more. Back then, average folk who’d been there for decades could still afford to live among the millionaires. The powerful who did have homes there (usually second homes) were considered avant garde bohemians.