My Life So Far (22 page)

His acting was fantastic. His precision was so perfect it made me want to be perfect. His relaxation was tremendous. I liked that. . . . And then, one day, I touched him at a time when I wasn’t supposed to be touching him. I just put my hand on his arm, and instead of that relaxed human being I felt steel. His arm was made up of bands of steel.

Of

course

he would hate the Method! But I’d found a home.*

2

CHAPTER TEN

DOUBLE EXPOSURE

When you’re a nobody, the only way to be anybody

is to be somebody else.

—A

NONYMOUS PATIENT,

Your Inner Child of the Past

I

N THE SPRING OF

1959, Josh Logan, after making a screen test with me, decided to put me under contract for $10,000 a year and launch my career with a movie version of a Broadway play called

Tall Story,

co-starring Anthony Perkins. It was to be shot at the Warner Bros. Studio in Burbank. What fascinated me most on the lot was the wardrobe department—two floors of a building, room after room of costumes from different periods, each tagged with the name of the movie and the star who had worn it. There were the muslin-covered body dummies of all the Warner Bros. stars: stout, thin, buxom, they had been created to the exact measurements of the stars’ bodies, ready for the seamstresses to pin their patterns to the forms. The dummies were headless, so if a particular shape intrigued you because of its dramatic curves (Marilyn’s) or its petite size (Natalie Wood’s), you’d have to ask one of the fifteen or so seamstresses whose it was. In the wardrobe department more than anywhere else, I felt awed in the presence of Hollywood history and realized I was about to step into that history myself. My measurements had been taken before I’d left New York and my dummy was right there next to the others, looking disappointingly straight up and down—with none of the eye-catching ins and outs that distinguished so many others.

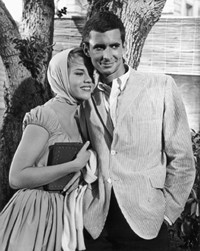

With Tony Perkins in Tall Story.

(Photofest)

Josh Logan directing Tony Perkins and me in

Tall Story

.

Then came the day for makeup tests. The Warner Bros. makeup department was run by the highly regarded Gordon Bau. Down the hall I could see Angie Dickinson getting hers done; Sandra Dee was next door. I lay back and presented my face to Mr. Bau, confident that he would make me look like a movie star. When he’d finished I sat up and

. . . Oh, my God! Who is that in the mirror! Is that how he thinks I should look?

I was horrified, dumbstruck. Who was I to tell him I didn’t want to be that person in the mirror? But this wasn’t me. My lips had a new shape and my eyebrows were dark and enormous, like eagle’s wings.

I hated the way I looked but didn’t dare say so. Then I was sent to get body makeup, done by a different person (union requirements) in a different room, with (

oh my God!

) mirrors all around. You could see everything. This was turning into a nightmare. A woman asked me to stand on a small platform while she wet a sponge with Sea Breeze and then put pancake body makeup over all the parts of my body that were going to be exposed. Since I was playing a cheerleader, that meant just about everything. To this day the smell of Sea Breeze brings back waves of anxiety. I began to think that this business of making movies wasn’t for people like me, who hated our bodies and faces.

The next day, when I saw the results of the costume and makeup tests, I wanted to disappear, so much did I hate how I looked onscreen—my face so round and my makeup so unreal. And I definitely didn’t have good hair. To top it off as one of the worst days of my life, word came down from Jack Warner, who had also seen the tests in his private projection room, that I must wear falsies. At the same time that he notified me of Mr. Warner’s demand, Josh suggested that after the filming I might consider having my jaw broken and reset and my back teeth pulled to create a more chiseled look, the sunken cheekbones that were the hallmarks of Suzy Parker, the supermodel of the time.

“Of course,” said Josh, touching my chin and turning me to profile, “you’ll never be a dramatic actress with that nose, too cute for drama.”

From that moment on, my experience on the film

Tall Story

became a Kafkaesque nightmare. My bulimia soared out of control and I began sleepwalking again as I had as a child, but in a different context. I would dream I was in bed, waiting for a love scene to be shot, and gradually I would realize that I’d made a terrible mistake. I was in the wrong bed, in the wrong room, and everyone was waiting for me to start the scene somewhere else, though I didn’t know where.

It was summertime and hot, so I often slept nude. On one occasion I woke up on the sidewalk in front of my apartment building: cold, naked, searching in vain for where (and who) I was supposed to be.

I was unable to rediscover the excitement I had experienced acting in Strasberg’s classes. I didn’t know how to use what I had learned there to make my cheerleader character more than one-dimensional. And the camera felt like my enemy. Standing before it, I felt as though I were falling off a cliff with no net under me. There was so much focus on externals, and there seemed no shortage of people who let me know that my externals could use some improvement—with one exception.

During a day off, I found a plastic surgeon who did reconstructive surgery, and I made an appointment to see him. In his office, I showed him my breasts and told him I needed to have them enlarged. To my amazement (and his credit), he got mad at me.

“You’re out of your mind to consider doing such a thing,” he said. “Go home and forget about it.”

But his validation wasn’t enough to put Humpty-Dumpty together again. All the things I feared most in myself—that I was boring, untalented, and plain—came to the fore during the filming of

Tall Story.

When it was done I returned to New York, vowing I would never go back to moviemaking.

I

was twenty-two, on my way to celebrity, earning my own living, and independent.

So why, when it was time for me to write about this period for my book, did I develop writer’s block that lasted six months? Oh, I had lots of excuses: There was all that thistle to spray at my ranch in New Mexico. There were rocks to move and trees to cut down to make horse trails, and then my kids were visiting. . . . You know, life. But after six months I had to face the fact that I was having difficulty confronting those years following the turning point with Strasberg. Why did the ensuing years feel so sad, so false, after things had started off so well? Not that there weren’t happy times, but pain engraves a deeper memory.

Does it seem strange that Strasberg’s classes allowed me to discover a place of truth, an authenticity, for the first time since childhood? The moment when I did my first exercise for him I felt he “saw” me. He was, after all, a master at sensing what was real and at naming it. All my life I had been encouraged

not

to probe my depths,

not

to identify and name my emotions. But Lee encouraged me to dig deep and to come out—and I did, all raw and vulnerable, reborn. Then,

wham!

My career began, and everything that had started to happen with Lee was pushed aside and it all became about hair and big cheeks and small breasts, and I couldn’t handle it, coming as it did on the heels of an emerging selfhood. I went into a three-year tailspin of private self-destruction, depression, and passivity. I don’t mean this by way of self-pity. There are a lot worse things in life than having your body critiqued, and stardom is a whole lot better than a kick in the ass. But my

Tall Story

experience pushed all my insecurity buttons. I

seemed

to be doing fine. Friends who were with me during that period may be shocked to read what I was really feeling. But then I always

seem

to be fine. I know how to get by.

For one thing, when I returned to New York from Hollywood I was bingeing and purging sometimes eight times a day. It was out of control, and as a consequence I was always tired, angry, and depressed. I briefly sought help from a Freudian psychiatrist, who sat behind me as I lay on a couch, where I was convinced that he was either sleeping or masturbating. I soon realized that talking to the ceiling about my dreams wasn’t what I needed. I needed immediate, look-me-in-the-eyes help—first to stop my bingeing and purging, then to help me understand why I was doing it. But I didn’t know where to go.

During this period I also developed a fear of men, and my sensuality took a long hiatus. I sought safety in the company of gay or bisexual men. This is also when ballet came into my life. With its rigidly prescribed moves and required slimness, ballet is the dance style of preference for women with eating disorders. Like anorexia and bulimia, ballet is about control. This was a time when women were not supposed to sweat; it was considered unseemly. The health clubs for women that existed featured saunas, vibrating belts that made your fanny wiggle, and other forms of passive exercise. Dumbbells and machines were strictly the domain of men. Consequently ballet was my first experience with hard, sweat-producing exercise that could actually change the shape of my body, and from 1959 until I began the Jane Fonda Workout in 1978, through all those early films, including

Barbarella

and

Klute,

wherever I was working, whether in France, Italy, the United States, or the USSR—ballet was my sole form of exercise.

Within a month of my return to New York after

Tall Story,

I began rehearsals with Josh for a play he’d purchased called

There Was a Little Girl,

written by Daniel Taradash. It dealt with rape. My father begged me not to do it, fearing that critics would find it too risqué. I saw it as a way to stretch myself beyond what I’d been asked to do in

Tall Story,

and although the script was flawed, it had an interesting, quasi-feminist-before-its-time premise: A young virgin is celebrating her eighteenth birthday with her boyfriend and hoping he will make love to her. He makes it clear he is not ready, they get into a fight, and she runs out into the parking lot, where a man rapes her, aided by a gang of his friends. She returns home in a state of shock and confusion to discover that, while they don’t say so overtly, her parents and sister (played wickedly by a fifteen-year-old, Joey Heatherton) assume it must have been her fault—the old you-must-have-wanted-it, blame-the-victim response. Knowing that she had wanted to have sex that night; believing that she may in fact have brought it on herself; and on the verge of a nervous breakdown, the girl goes in search of her rapist, hoping to find out directly from him where the truth lies.