My Life So Far (31 page)

It was a tough shoot, lots of scrapes and bruises. I was attacked by little mechanical dolls. I was shut into a tiny plastic box with hundreds of birds, flying, pecking, and pooping on my hair, arms, and face. I was constantly being asked to slide down clear plastic tubes or stand inside a cloud of noxious fumes. When I see what actors in action films have to do these days, however, I think I got off pretty light.

By today’s standards

Barbarella

seems slow (it seemed slow to many critics back then as well). But I think the jerry-built quality of the effects and the offbeat, camp humor give it a unique charm. Pauline Kael, film critic for

The New Yorker,

wrote about my performance: “Her American-good-girl innocence makes her a marvellously apt heroine for pornographic comedy. . . . She is playfully and deliciously aware of the naughtiness of what she’s doing, and that innocent’s sense of naughtiness, of being a tarnished lady, keeps her from being just another naked actress.”

“Just another naked actress” indeed! I can laugh about it now, but the tensions and insecurities that haunted me during the making of that film almost did me in. There I was, a young woman who hated her body and suffered from terrible bulimia, playing a scantily clad—sometimes naked—sexual heroine. Every morning I was sure that Vadim would wake up and realize he had made a terrible mistake—“Oh my God! She’s not Bardot!”

At the same time, unwilling to let anyone know my real feelings and wanting, Girl Scoutishly, to do my best, I would pop a Dexedrine and plow onward. The “American-good-girl-innocence” that Pauline Kael described was really the Lone Ranger trying to “make it better.”

Vadim’s drinking had gotten much worse. He was a binge drinker: He would go for weeks and months without a drop (unfortunate, because it allowed him to feel he had the disease under control), but then things would seem to disintegrate. Partway through the shooting of

Barbarella

he started drinking at lunch, and we’d never know what to expect after that. He wasn’t falling down, but his words would slur and his decisions about how to shoot scenes often seemed ill-considered. When I watch certain scenes from the movie now, I remember all too well how vulnerable I felt at the time. And more and more angry!

I was also growing more remote, feeling as if I were out on a limb (or a steel pole) by myself, that no one else seemed to care about what I cared about—like showing up to work sober and on time, getting a good night’s sleep so you’d be prepared and creative the next day. But I still lacked the confidence to try to take charge when Vadim seemed particularly out of control.

Today

Barbarella

’s production costs would seem penny-ante, but for the time they were considerable. The cast and crew were large and multilingual, the technical challenges awesome, and too many things, including the script, hadn’t been worked out sufficiently in advance. Often I would have to pretend to be sick so that the film’s insurance would cover the cost of a shutdown for a day or two while Vadim, Terry Southern, and the others figured out script problems. One thing for sure, I never dreamed the film would become a cult classic and, in some circles, the picture Vadim and I would be best known for. It has taken me many decades to arrive at a place where I can understand why this is so and even share the enjoyment of the film’s unique charms.

There was another feeling that began to nudge me. It was just a hint of something I could not yet name—the old feeling of being in the wrong place. But this time it wasn’t the feeling there was a party going on that left me out. No. Now my life

was

the party—one long, unending party that I didn’t especially want to be at. Rather, it was a feeling that something more important was going on out there and my life was being frittered away with whatnots and doodads. There were the struggles of blacks in the United States that I’d only just started to learn about. There was a growing anti–Vietnam War movement. But I hadn’t followed the war news closely, and when Vadim’s French friends criticized the U.S. involvement there, my reaction was usually defensive. I simply couldn’t believe that America could be involved in a wrong cause, and I hated having foreigners criticize us. I was totally clueless about the nascent women’s movement and would have felt deeply threatened by it had I been exposed to feminism.

It wasn’t any specific alternative life I longed for, it was just a sense of growing malaise. I was a go-alonger, a passive participant, living “as if”:

as if

I had a good marriage,

as if

I were happy and fully present. I was also trying not to be too serious about anything, because if you took things too seriously, it meant you were bourgeois and didn’t have a sense of humor. There was a certain tyranny about Vadim’s “don’t take things too seriously” mandate, especially when it came to women.

When filming on

Barbarella

finished in the fall of 1967, it occurred to me that perhaps I could quiet the malaise and fill the empty place that seemed to be growing larger by having a baby.

Make it better.

One of the things I liked most about Vadim was how he was as a father. Perhaps it was due to the fact that he’d never entirely grown up himself that he seemed able to inhabit a child’s world. His lack of concern about punctuality and the doing of duties served him well when it came to his little children. Every night, after I’d badgered Nathalie into brushing her teeth and going to bed, Vadim would pick up the thread of some phantasmagoric tale he’d have concocted for her. Sometimes the story would go on for weeks. Usually there was an element of science fiction, always of whimsy, with little people turning out to have wondrous big powers. Besides his stories, there were his paintings: Vadim had a unique painting style—primitive, colorful, sensual, in many ways the drawings of a child. Then there was his patience and his generosity with his time—two elements critical to good parenting: Vadim could spend hours debating with his children the origins of the universe, life after death, the meaning of gravity, the whys and wherefores of life, all with a charm and attention that moved me deeply. He was totally present, at least for his girls, at least when they were little. Come to think of it, it was always true for our Vanessa, too.

Like many people who feel their marriage dissolving, I thought that if I had a child, it would bring us closer. But the desire for a baby wasn’t only to save a troubled marriage, it was a way to save

me.

I thought that the experience of childbirth would somehow make me right, that the pain of natural childbirth would deliver me to myself. I still saw myself as deeply flawed, unable to open my heart and love enough to be truly happy.

Vadim thought that having a baby was a splendid idea, so I had my IUD removed, and a month later, during Christmas vacation in Megève, a ski resort in the French Alps—a week after my thirtieth birthday, on December 28, 1967, to be exact—I conceived. I knew the moment it happened and told him so—there was a different resonance to our lovemaking.

I had a whole round year ahead of me with no commitments except to complete work on our farm, which included planting a garden and a forest. Though I have no conscious memory of my father transplanting the huge pines and fruit trees he brought onto our Tigertail property in the forties, I’m told that he did. I’ll wager that way back then is when I got bitten by the tree-transplanting bug that is a trademark of mine. I’m not big on jewelry or fashion, but big trees—now,

that’s

something I’ll spend money on. I justify it now by pointing out that I’m too old for saplings.

I decided I wanted some very large hardwood trees in our front yard, maples, poplars, birch, catalpa, liquidambars. So I drove all over France to the largest nurseries with the tallest trees I could buy, so tall that they had to be transported at night and telephone lines had to be taken down to let them pass. A friend had given us her car, a 1937 Panhard Levasseur, a real collector’s item—but since it no longer ran, I had a welder cut it in half and then solder it together around a newly planted plantain tree so that the tree was growing right through the car—a piece of yard sculpture.

It was in one of the nurseries, searching for trees, that I felt the first wave of nausea. It stopped me in my tracks. I knew exactly what it meant. I didn’t need a pregnancy test to tell me. I broke into a cold sweat, returned to my car to sit down—and was overcome by a sense of dread! I felt I had to muster all my forces against an unknown terror that seemed to have invaded me.

Why? I wanted this!

Then tears came, then racking sobs.

What is happening? This isn’t how I’m supposed to feel!

And then I knew: The pregnancy was incontrovertible proof that I was actually a woman—which meant “victim,” which meant that I would be destroyed, like my mother. It was one of those strange moments when I was feeling what I was feeling while simultaneously standing outside of myself analyzing the feeling—and being shocked by what it meant.

A month or more into the pregnancy, I began to bleed and was told I couldn’t leave my bed for at least a month if I wanted to prevent miscarriage; I was given DES (diethylstilbestrol) to prevent miscarriage, a drug that has subsequently been linked to uterine cancer in daughters of mothers who’ve taken it. Then I came down with the mumps.

I saw these problems as a powerful sign that I was not meant to be a mother, and they provided me with a reasonable justification for backing out of the whole thing. Yet when my French gynecologist recommended I have an abortion because of the risk mumps posed to the fetus, I never for a moment considered that as an option (though I was grateful I had the choice). It’s not that Vadim and I weren’t concerned. But my attachment to motherhood was so tenuous that I felt if I aborted the fetus, I would never want to have another baby. It was a low point in my life, let me tell you: I had just turned thirty and was pregnant, bedridden, and risking a miscarriage; mumps had swollen my face to the size of a bowling ball; and to top off my misery, across the ocean Faye Dunaway had just created a sensation in

Bonnie and Clyde.

Not that I was competitive or anything.

I had just entered my second act, and as far as I could tell, my life had peaked and was on the decline.

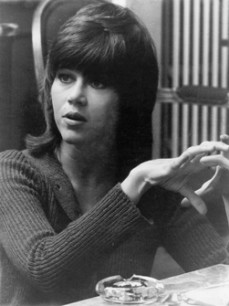

I was always at meetings.

My mug shot.

(AP/Wide World Photos)