My Life So Far (64 page)

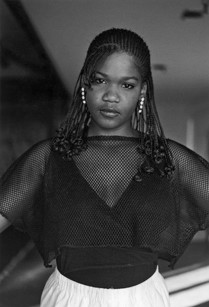

There was a beautiful eleven-year-old black girl from Oakland named Lulu. Everyone loved her. She had a laugh like a cascade of wind chimes. Her parents had been members of the Black Panther party, and her uncle worked with Tom. Lulu came for two years running, and then for several years we saw no more of her. When she returned at age fourteen, she had changed. She slept all day, couldn’t tolerate being in a crowd, rarely spoke, and had terrible nightmares every night. At the end of the camp session, she confided to a counselor that she had been brutally molested by a man over a prolonged period of time. She had told no one because the man threatened to kill her and her family if she did.

Lulu was suffering from severe posttraumatic stress disorder, sleeping most of the time (as PTSD sufferers are prone to do), and getting D’s and F’s in school despite her innate intelligence. She had come back to camp because she needed to tell someone. I made a deal with her that if she brought her grades up to B’s by the end of the school year, I would get her into a school in Santa Monica and she could stay with us.

Lulu was fourteen when she came into our home and had been with us for about a month when one morning she came up to me as I was washing breakfast dishes and said, “I need to say something, but I’m a little ashamed.”

“It’s okay, Lulu, go ahead.”

“I never knew till being here that all mothers don’t beat their children.”

I realized that simply allowing this young woman to be in a home where children disagreed with their parents and weren’t beaten for it, where people sat at the table and talked together, was opening up a new world to her. Frankly I often wonder which of us has learned more from the other, Lulu or me.

I asked her once why the camp was an important experience for her. She hesitated for a moment before answering. “It’s the first time I’ve been with people who think about the future.”

That stopped me short, and coming to terms with what it implied has framed the way I see my work today with children and families in Georgia. There’s a saying: “The rich plan for generations; the poor plan for Saturday nights.” Middle-class folks take for granted that we have a future that requires planning for. To never think about the future means you live without hope.

One day while we were driving back from Laurel Springs, Lulu announced to me that she wanted to have a child.

“Why?” I asked, taken aback.

“I want something that belongs to me,” she answered simply and honestly.

“Get a dog!” was my reply. Then I went on to talk with her about what would happen to her life if she had a child to care for before she was an adult woman. Having a child has few consequences if you don’t see a future for yourself. When I once heard Marian Wright Edelman, president of the Children’s Defense Fund, say, “Hope is the best contraception,” I knew because of Lulu how true these words were in relation not just to early pregnancy, but to drugs, violence, and a host of other behaviors that are indicators of hopelessness.

Lulu did not have a child. She went on to graduate from college, got herself into graduate school in public health at Boston University (with no help from me), and has developed into a remarkable success story. Filled with intellectual curiosity and commitment to justice, she remains a member of my family. Early in her life Lulu had received just enough love from her mother to instill resilience in her, which is what enabled her to survive—spirit intact—later difficulties, of which her sexual molestation was but one example. Lulu also attributes her resilience to the Black Panther party in Oakland.

Lulu, age thirteen.

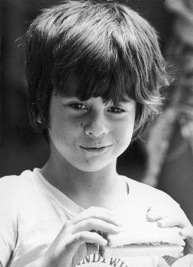

Troy, age six.

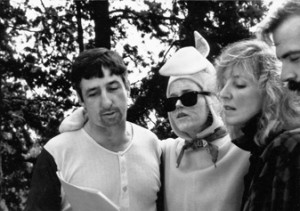

Singing hymns with Tom and Mignon McCarthy at our annual Easter bash at the ranch. I was always the Easter bunny. I miss that.

“I grew up with the Panther programs—their hot breakfasts and the things they did for kids. They were like my family.”

Sometimes I feel as though I have a magnet on my skin and when I walk through the world the relevant input I need for my journey jumps out from the hurly-burly and sticks to me. That’s the way it was at Laurel Springs.

I

needed the lessons the camp taught over those fourteen years.

M

y children had their own learning experiences. Both Vanessa and Troy grew up feeling different from others their age. Vanessa lived in two countries, spoke two languages, experienced two styles of parenting. “I liked having two lives—being different,” she says. “I still do.”

Troy’s sense of difference didn’t start until he entered a public junior high school and students would ask him why he wasn’t driven to school in a limousine since his mother was a movie star. “This made me uncomfortable because it made me feel I was being looked at as a material object. I had never before had any awareness of material things or of the paradoxes of my life—living simply the way we did, yet you being famous. I began to feel like a misfit. But the best thing about being a misfit is that it attracts you to other misfits. And they’re usually the most interesting people.”

One area in which Troy realized there were differences with his friends had to do with the nature of his extended family. “Whereas my friends had aunts, older sisters, grandmothers, to assist in raising them,” he told me recently, “I had au pairs, nannies, political organizers, and your assistants. You were my ‘core mother,’ and then you had tentacles. Dad would be one. Laurel Springs was another.”

For Vanessa and Troy, camp provided a safe setting for many firsts: first kiss, slow dancing, wilderness. For Lulu, it provided a future.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

THE WORKOUT

There are no gains without pains.

—B

ENJAMIN

F

RANKLIN

Great ideas originate in the muscles.

—T

HOMAS

E

DISON

I

T WAS EXPENSIVE

running a statewide nonprofit organization like CED in a state as big and diverse as California, and the weakness in the economy was making it increasingly difficult to raise the necessary funds. I was making one or more movies a year by now

—Julia, Coming Home, Fun with Dick and Jane, The China Syndrome, Comes a Horseman, California Suite—

most quite successful, and every premiere would be a benefit for CED. Still, we worried about being able to sustain the work.

Then I read an article about Lyndon LaRouche, founder of the National Caucus of Labor Committees. (You may remember back in the late seventies seeing people standing in major airports with signs saying things like “Jane Fonda Leaks More Than Nuclear Power Plants” or “Feed Fonda to the Whales.” Those people had ties to LaRouche, as did some of the goons who went into bars to beat with chains people they suspected of being gay.) This article said that LaRouche’s organization was financed, at least in part, by his computer business. That set Tom and me thinking: Why not start a business that would fund CED? For a while we considered going into the restaurant business, and we actually spent a month or so driving around looking for one to buy, asking people what went into running a successful restaurant. We also toyed with the idea of an auto repair shop where people wouldn’t be ripped off.

One day John Maher, charismatic co-founder of Delancey Street, an entrepreneurial halfway house for addicts, said to me, “Never go into a business you don’t understand.” That was about the best business advice I have ever received, but it not only ruled out the restaurant and car repair ideas, it seemed to narrow our options to zero. What did I know about

any

business?

As it turned out, plenty. I just had to see what was staring me in the face.

I

n 1978, while filming

The China Syndrome,

I again fractured my foot, so ballet became impossible for me, at least for the foreseeable future. For more than twenty years ballet, with its strict classical structure and music, had been my haven, my way of staying in shape and keeping at least a tenuous connection to my body. What to do? I had to get into shape for my next movie,

California Suite,

in which I had to appear in a bikini. Understanding my urgency, my stepmother Shirlee suggested that when the foot was sufficiently healed (where was that Vietnamese chrysanthemum poultice when I really needed it?), I should check out a class at the Gilda Marx studio in Century City, California. The instructor was marvelous, Shirlee said. Her name was Leni Cazden.

Leni was in her early thirties, about five feet five, with short copper-colored hair, green eyes, narrow hips, and an enigmatic combination of aloofness and availability. Her class was a revelation. I entered so-called adult life at a time when challenging physical exercise was not offered to women. We weren’t supposed to sweat or have muscles. Now, along with forty other women, I found myself moving nonstop for an hour and a half in entirely new ways.

Leni’s class wasn’t what would soon become known as aerobics. For something to be aerobic it needs to get your large muscle groups—your thigh, hip, or upper body muscles—working steadily so as to increase your heart rate for at least twenty minutes. This is the form of exercise that burns fat calories and strengthens the heart. But Leni, I would discover later, was a smoker and aerobic activity wasn’t for her. Instead her routine was more about strengthening and toning through the use of an interesting combination of repetitive movements that included, to my great pleasure, a surprising amount of ballet, which Leni had learned during her early days as a competitive ice-skater.