Map of a Nation (33 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

On 20 August 1797 the

Observer

newspaper was able to proudly report that ‘Colonel Williams and Captain Mudge of the Artillery, who have for several years past been engaged in a general admeasurement of the

kingdom

, have compleated [

sic

] a very minute survey of all the Southern and Western Coast to the Bristol Channel’. Britain’s entire south coast, from the eastern extremity of Kent all the way to Land’s End, and then up the northern coast of Cornwall and on to Bristol, had been measured through sight lines that traced imaginary triangles onto the landscape. But in March 1799 the Master-General of the Ordnance, Charles Cornwallis, commanded Mudge to suspend his own plans for the Trigonometrical Survey and head straight for the unmapped part of Essex, which he designated the Ordnance Survey’s highest priority and the subject of its next map. Possessing such a large expanse of coastline and presenting easy access to London, Essex was vulnerable to a French invasion and therefore was thought to urgently need an Ordnance Survey map.

Mudge dutifully spent the spring and summer of 1799 triangulating north-east from London. He first measured a new ‘base of verification’ to serve a similar purpose to that on Salisbury Plain, but this time between Hampstead Heath to the north and Severndroog Tower on Shooter’s Hill, south-east of Greenwich. From this London baseline, Mudge planned to observe triangles proliferating over to Hanger Hill in west London to Bushy Heath near Watford, to Brentwood Church spire, to Gravesend, Langdon Hill in Essex and Tiptree Heath, north of Maldon. But initially it proved difficult. The smog of the late-eighteenth-century city proved impenetrable to the Great Theodolite’s sights, even when Mudge used surveying flares

bright enough to be seen across the English Channel. It was impossible to observe between Hanger Hill and Severndroog Tower, fifteen miles apart, and Mudge was forced to use the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral as an

intermediary

trig point.

There is something charming about the image of William Mudge and his theodolite perched on St Paul’s cross and ball, high above the bustle of the City. Did Mudge, like Wordsworth, reel at the seeming chaos below him? ‘What a shock/ For eyes and ears!’ the poet cried in 1802. ‘What anarchy and din,/ Barbarian and infernal, - a phantasma,/ Monstrous in colour, motion, shape, sight, sound!’ Or did Mudge instead revel in it, like another contemporary, the essayist Charles Lamb? Lamb loved

the lighted shops of the Strand and Fleet Street; the innumerable trades, tradesmen, and customers, coaches, waggons, playhouses; all the bustle and wickedness round about Covent Garden; the very women of the Town; the watchmen, drunken scenes, rattles; life awake, if you awake, at all hours of the night; the impossibility of being dull in Fleet Street; the crowds, the very dirt and mud, the sun shining upon houses and pavements, the print shops, the old bookstalls, parsons cheapening books, coffee-houses, steams of soups from kitchens, the pantomimes – London itself a pantomime and a masquerade … I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fulness of joy at so much life.

Mudge admitted that he was forced to measure his London baseline more cursorily than the others, hindered by its abundant buildings and population and the opaque air. But soon the triangulation of Essex was under way, and in the season of 1799 the Trigonometrical Surveyors covered an area of around 5000 square miles as far north as Coventry and as far west as Broadway Beacon in Gloucestershire. Mudge was soon joined by the Interior Surveyors, who began mapping the county in detail alongside the Trigonometrical Survey. On 15 August London’s

Courier and Evening Gazette

recounted the progress of the secondary triangulation with interest,

describing

how the map-makers ‘of the drawing room in the Tower’ were following ‘Captain Mudge with a portable theodolite, for determining the exact

situation

of every church and remarkable object’, before ‘fill[ing] up the plans in a style of accuracy and elegance never hitherto attempted’.

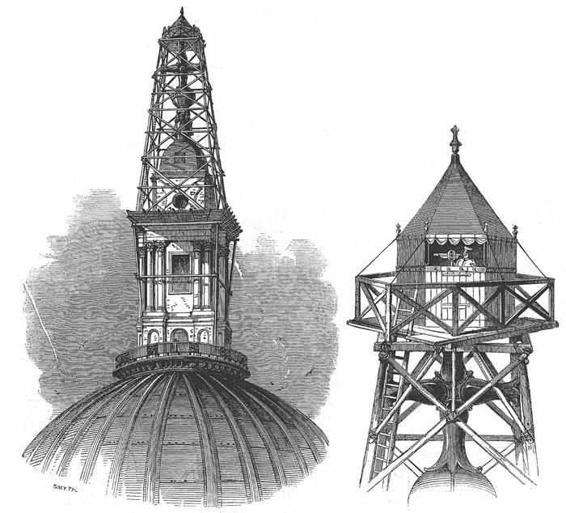

26. Images of the Ordnance Survey’s perilous task to measure from the cross and ball on St Paul’s Cathedral in London in 1848.

Mudge, however, had serious reservations about the Interior Surveyors’ work. He was not worried by their accuracy or attentiveness to the

landscape

– quite the opposite, in fact. He fretted that the enormous six-inch scale on which the map-makers had begun surveying Kent, and the

three-inch

scale that they subsequently adopted, risked creating an overcrowded map that took too long to complete. ‘It does not appear that any advantage will accrue to the Board [of Ordnance], from surveying all the fields of it,’ he wrote to a superior. Mudge did not want the Interior Surveyors to spend time mapping any aspect of the landscape that would not find its way onto the engraved map. A superfluity of detail on the fair plans would place an enormous onus of responsibility onto the engravers, who would then have to

select what to include and omit on the final maps. Concerned that the engravers were not sufficiently trained in this respect, Mudge emphasised the benefit of ‘relinquish[ing] the prosecution of the very minute part of the Survey’ to ‘attend to what is of real use to the Public at large’, another example of his prioritisation of popular concerns over military priorities. He suggested that, if the Interior Surveyors made their maps of Essex on the reduced scale of two inches to a mile, the completed chart would cost ‘about one third of the sum which has lately been expended in making the map of Kent’ and would consume ‘less than a quarter of the time’. He provided the Board with an estimate of 33s per square mile to make a county survey of Essex, which, when combined with the expenses of the triangulation and travelling charges, produced a total cost of

£

2422. And he predicted that on this basis it would take fifty more years to create maps of the whole of England and Wales. Persuaded by these figures, the Board of Ordnance readily agreed to Mudge’s proposition and ‘much applaud[ed] the zeal which he has shewed in producing so considerable a saving of expense’.

In 1800, the Interior Survey underwent radical change. At the beginning of that year, William Gardner, chief draughtsman in the Tower of London’s Drawing-Room, and the creator of one of the best maps yet of a portion of the English landscape – the 1795 revival of the Great Map of Sussex –

unexpectedly

died. He was replaced by William Test, who was charged with overseeing the Interior Survey’s progress into the next century. And shortly after Gardner’s death, all the remaining draughtsmen in the Tower

experienced

a dramatic alteration of status. Up until then, the Tower map-makers had all been civilians at the heart of a martial establishment. But in December 1800, under the pressure of the Napoleonic Wars, a Royal Warrant reconstituted the Tower draughtsmen, including the Interior Survey’s staff, into a ‘Corps of Royal Military Surveyors and Draftsmen’: they were given military status. Although this would be reversed after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, for the next seventeen years these men found

themselves

formally subject to the ‘rules and disciplines of war’ and presented with a new blue uniform to wear, similar to that of the engineers.

The Interior Surveyors duly mapped Essex on the scale of two inches to one mile, for which they were paid 32s 6d per square mile. Each member of

the team was instructed to ‘represent the Towns, Villages, Woods, Rivers, Hills, omitting only the [boundaries] of the Fields’. Once the problem of scale was overcome, Mudge applied himself to formalising the relationship between the Ordnance Survey and the engravers who had produced the first chart. He hired Thomas Foot, who had worked on the Kent map, and a man called Knight, to work at the Tower of London on a permanent basis for six hours a day, for which they were promised respectively 3½ and 2½ guineas per week: a very reasonable wage. William Faden remained the chief

overseer

of the engraving and was given the official title of ‘Agent for the sale of Ordnance maps’.

By 1803 the Essex map had been engraved in outline, minus its hills, and proof sheets were ready for distribution, to invite corrections to its place names. Engraving the maps’ details was time-consuming and it took two more years until, on 18 April 1805, it was published in four sheets of 23 by 34¾ inches, under the title ‘Part the First of the General Survey of England and Wales’. Sheet number one stretched from London Bridge in the west to the River Medway and Rochford in the east, and from Broxbourne in the north to Dartford in the south. Sheet number two sprawled from Osea Island in the west to Foulness and the Thames estuary in the east, and from Goldhanger in the north to Sheerness in the south. The remaining two sheets covered the northern aspects of the county of Essex, and extended from Bishops Stortford in the west to Harwich in the east, and from Manningtree and Saffron Walden in the north to a few miles above Chelmsford in the south.

The Kent survey had been produced as a stand-alone presentation map and had relied on a temporary contract between Faden’s engravers and the Board of Ordnance. But the Essex charts were the products of a permanent engraving arrangement that saw the Board of Ordnance turned into a

map-publisher

, and Mudge conceived of those Essex maps as the first elements of a numbered series of overlapping sheets that would eventually envelop the entire nation. The Ordnance Survey has a number of possible birth-dates, in the Paris–Greenwich triangulation of the 1780s and the date in 1791 when Lennox bought the theodolite and appointed Williams and Mudge to

commence

a national trigonometrical survey. There are also numerous contenders

for its ‘First Map’: Gardner and Gream’s map of Sussex of 1795 or the Kent survey of 1801. But the appearance in 1805 of sheet number one (of Essex) marked the birth of the Ordnance Survey as we now know it, an agency whose mapping systematically covers the entire nation. Today the Ordnance Survey’s orange

Explorer

maps divide Britain into 403 intersecting squares on a scale of 1:25,000 (or 2½ inches to a mile) and its pink

Landranger

series covers it in 204 segments, on a scale of 1:50,000 (or 1¼ inches to a mile). The publication of the Ordnance Survey’s maps of Essex marked the moment when young map-readers could for the first time anticipate possessing a complete and unprecedentedly accurate map of England and Wales within their lifetime. In 1872, when the creation of a second or ‘New Series’ of Ordnance Survey maps was authorised, this original sequence of maps became known as its ‘First Series’ or ‘Old Series’. But that series would not be completed until way beyond Mudge’s estimate of fifty years. Wanting to make the maps as complete an image of all aspects of the nation’s face as

possible

, the Ordnance Survey would not publish the last map of the First Series until 1870.

M

ANAGING THE

Trigonometrical Survey, while simultaneously

overseeing

the Interior Survey and the engravers, consumed every moment of William Mudge’s attention and sent him all over the country. He did not even have a permanent base in London and had been lodging in apartments in his workplace at the Tower of London since the Ordnance Survey’s

foundation

in 1791. It would have been impracticable for Mudge to have moved his family. With his wife Margaret, he now had five children: a daughter, Jenny (‘a more meritorious, sensible and affectionate woman does not live,’ her doting father wrote), and four sons: Richard Zachariah, John, William and little Zachariah. They would have been cramped in the Tower of London, from which Mudge himself was absent for much of the year. So his family continued to live in Devon, over a day’s coach journey away from the map-maker himself. By the end of the first decade of the Ordnance Survey’s progress, the weight of responsibility and this separation from his loved ones

had begun to weigh on him. It was said that ‘he often complained of

depression

of spirits

, but found relief from exercise on horseback. It was rather singular, however, that he always got into most unfrequented parts of the country in his equestrian excursions.’