Map of a Nation (28 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

Mudge and Dalby’s actual measurement of the Salisbury Plain baseline did not begin until the end of the following June and it was completed in around seven weeks. The map-makers did not have the luxury of delay. It was imperative that the baseline should be finished before early autumn, ‘when the cultivated ground a mile to the northward of Old Sarum would be ploughed’. Like Hounslow Heath, the Salisbury Plain baseline was an eerie setting for their work. The men shared the land with what Wordsworth described as ‘an antique castle spreading wide’, ‘Pile of Stonehenge!’ This giant stone circle, an icon of British history, was just over four miles from the northern end of the Ordnance Survey’s baseline. Thought by some to be a celestial map ‘by which the Druids covertly expressed/ Their knowledge of the heavens, and imaged forth/ The

constellations

’, Stonehenge could be seen as an ancient counterpart to Mudge and Dalby’s own endeavour. Wordsworth also described how the Plain was etched over with giant crop circles and chalk shapes, ‘strange lines’ left ‘on the earth … by gigantic arms’, which also may have reminded the

map-makers

of their own triangulation. But for Wordsworth the strange,

inexplicable stone circle seemed to symbolise the nation’s profound

indifference

to his isolated and disappointed wanderer and the poet complained how this ‘proud’ phenomenon seemed ‘to hint yet keep [its] secrets’. As Wordsworth’s sailor ‘plodded on’ past Stonehenge, he heard the ‘sullen clang’ of ‘a sound of chains’ and ‘saw upon a gibbet high/ A human body that in irons swang’.

Salisbury Plain is now inhospitable in a different way. Since 1898 the Plain has been used for Army training. The Ministry of Defence owns 150 square miles, over half of the old Plain. It houses an aerodrome, the Royal School of Artillery, a host of camps and barracks, and even a deserted village called Imber, used for training in built-up-area warfare, especially during the Northern Irish troubles. Live firing takes place on 340 days a year and around thirty-nine square miles are permanently closed to the public. Access to the rest is severely limited. But the Plain’s enforced hostility to humans has made it peculiarly hospitable to wildlife. Its chalk grassland has not been lost to agricultural cultivation, and Salisbury Plain now boasts ‘the largest known expanse of unimproved chalk downland in north-west Europe, and

represents

41 per cent of Britain’s remaining area of this rich wildlife habitat’. It has been classified as a Site of Special Scientific Interest and supports around eighty species of internationally rare plants and invertebrates. It is wonderful for birds – in 2003 the Great Bustard was reintroduced to Britain on Salisbury Plain. Many of the features that William Mudge saw in the old Plain, such as its relatively unpopulated and unenclosed landscape, its

flatness

and expanse, were the same things that later attracted the military to the place and also lie behind its now thriving ecosystem.

B

Y THE END

of the summer of 1794 the map-makers had ‘laid down’ the coast ‘from Fairlight Head to Portland’ and some of the inland territory that joined the coast to the capital. Portland is a spit of land in Dorset, just south of Weymouth, and it is separated from Fairlight Head in East Sussex by a distance of about 136 miles. In just three surveying seasons, William Mudge and Isaac Dalby, with a little help from Edward Williams, had measured two baselines, triangulated through five counties (including parts of the capital), and visited three more to conduct a reconnaissance that would determine the future

direction

of the Trigonometrical Survey. It was a remarkable achievement.

C

HAPTER

S

IX

T

HE MAP-MAKERS

did not pass through the British landscape like ghosts. The sight of a small team of men encamped at the crest of a nearby hill, bustling around a mysterious, squat piece of machinery, and scanning the horizon for rhythmic flashes of light inevitably caught the attention of locals. There was a healthy appetite for public displays of map-making prowess during the Ordnance Survey’s first decade. In 1800 Londoners flocked to a demonstration of ‘Geometrical and Trigonometrical Operations’ at the Establishment for Military Education in Knightsbridge, of which

The Times

gave an enthusiastic write-up. And the Ordnance Survey’s endeavours, which were more authentic, proved equally attractive. Wealthy landowners volunteered the turrets, pinnacles, follies, obelisks and cupolas that adorned their mansions and estates as secondary trig points.

William Mudge’s presence in the landscape remained visible for months after he had left an area. The surveyors constructed cairns – small mounds of rough stones – to indicate the exact spots at which their theodolite had been placed, to allow the measurements to be redone or verified in future. Newspapers pleaded with locals to leave these memorials untouched. Since 1935, when the Ordnance Survey retriangulated the first Trigonometrical Survey, trig points have been designated more permanently by squat, square, concrete pyramids or obelisks that each bear a brass plate marked OSBM (Ordnance Survey Bench Mark) and with the reference number specific to

that station. Although now largely obsolete, having been replaced by Global Positioning Systems, aerial photography and digital mapping with lasers, these concrete trig points are still preserved in the landscape, on hills and plains alike. They are emblems of a productive relationship between

humanity

and the natural world, and are valuable tools of orientation for hikers: one is generally guaranteed a good view from an elevated trig point.

The Ordnance Survey’s work attracted attention from the press as well as from the general public. During the triangulation’s first summer,

Lloyd’s

Evening

Post

reported that ‘a Survey of the Island of Great-Britain, upon a grand and important scale, has been undertaken by his Grace the Duke of Richmond’. Many newspapers were happy that the foundations laid by William Roy’s endeavours were being built upon by a new generation. And once the triangulation was under way, some journalists were enthralled by Mudge’s operation as a feat of human exertion. When the Ordnance Surveyors encamped at Bath, at least two national newspapers offered a charming account of how ‘the novelty of half-a-dozen tents pitched in that part of the country, cannot fail of attracting the wonder of the surrounding multitude, whose curiosity leads them thither by hundreds at a time. The unknown and supposed magical powers of the surveying instruments, with the flag-staffs, which they erect on neighbouring eminences, suggest the ideas of telegraphs and invasion.’

In early 1794, the Ordnance Survey’s nominal director, Edward Williams, a man well acquainted with the machinery of self-promotion, sought the advice of Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, about capitalising on the popular fascination with the project. Banks mooted the idea of

publishing

accounts of the Trigonometrical Survey’s progress in the journal of the Royal Society, the

Philosophical Transactions

, the publication in which William Roy had described his endeavours with such success that the

relevant

issues had sold out. Banks became even more enthusiastic when the Board of Ordnance offered to entirely cover any costs accrued by

illustrations

for those articles and placed a bulk order for ‘five hundred Copies’ of the volumes.

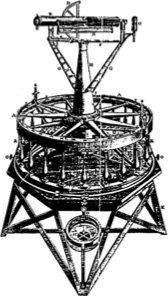

On 25 June 1795 the first ‘Account of the Trigonometrical Survey’ was read before an intrigued audience of Royal Society fellows. The article

began by delineating the trajectory from which the Ordnance Survey had emerged. It recalled its origins in Roy’s official statement in 1766 of the need for a complete national map, and then described the measurement of the base on Hounslow Heath and the triangulation through Kent during the Paris–Greenwich triangulation. And then, in businesslike prose, Williams and Mudge set about recounting their own experiences of remeasuring the Hounslow Heath baseline: the instruments that had been employed; the complex mathematical calculations that had been used to determine their apparatus’s ‘rate of expansion’ in different temperatures; and the iron cannon with which they had marked the base’s extremities. They told their audience about ‘the Commencement of the Trigonometrical Operation’, ‘the Improvements in the great Theodolite’, and the progress they had made in the triangulation between 1792 and 1794, giving details of the selected trig points and their bearings from one another. Finally, Williams and Mudge described the measurement of the ‘Base of Verification on Salisbury Plain with an Hundred Foot Steel Chain, in the Summer of the Year 1794’. They were clearly overjoyed that their calculations had shown that the actual measurement of the baseline accorded very closely with the figure that had been derived through trigonometric formulae from the angles that had been measured with the theodolite. The article was published shortly afterwards in the

Philosophical Transactions

and Mudge proudly presented a bound copy to King George III.

Two years later, in May 1797, Mudge read and published a sequel, a second ‘Account’ which described the Trigonometrical Survey’s progress in 1795 and 1796. Encouraged by the public demand for these two articles, in the eighty-fifth and eighty-seventh volumes of the

Philosophical

Transactions

, Mudge and Dalby set about collating their papers and adding a lengthy

preface

to make a book-length text, which they published in 1799 as volume one of

An Account of the Operations Carried on for Accomplishing a Trigonometrical Survey

of England and Wales

. Sold at

£

1 8s (which represented nine days’ wages for a craftsman in the 1790s), the volume was certainly expensive, but not

prohibitively

so. Mudge wanted his account of the Ordnance Survey’s early progress to reach a wider audience than the specialised readers of the

Philosophical Transactions

.

In the early days of the Ordnance Survey, Williams and Mudge had accepted that, in the absence of any formal plan to turn their

trigonometrical

data into military maps, that information would be used by civilian surveyors. They had good reason to believe this, because in 1793 two

map-makers

called Joseph Lindley and William Crosley had published a map of Surrey that was based on trigonometrical information from William Roy’s published accounts of the Paris–Greenwich triangulation. Roy’s godson and sometime assistant was a man called Thomas Vincent Reynolds, to whom he had left his most prized possessions, including his military commissions, his Copley Medal, a watch and a miniature portrait of Roy by Maria Cosway. In that same year, after Britain’s entry into the French Revolutionary Wars, the Board of Ordnance had appointed Reynolds to use Mudge’s Trigonometrical Survey data as the basis for a rapidly executed ‘Military Map of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and part of Hampshire’, a small-scale survey showing the roads on which troops and artillery might be mobilised in the event of an invasion.