Map of a Nation (32 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

T

HE PUBLIC APPEARANCE

of the first Ordnance Survey map had been eagerly anticipated. The Austrian general Andreas O’Reilly was surely not the

only one to exclaim, upon witnessing this remarkable feat of cartography ten years after its first publication: ‘the map of Kent was by much the finest piece of Topography in Europe’. On 13 January 1802 Mudge ‘presented the Map to his Majesty’. But George III, who suffered from bouts of insanity, was clearly not entirely engaged with the significance of the achievement, and Mudge commented: ‘I think [he] still remains to be informed, that it is

an

actual map

, and not a written account similar to the last presented.’ In 1816, a group of foreign dignitaries requested a private viewing of this iconic achievement. On being informed that the ‘Arch Dukes wanted to see everything connected with the Survey’, Mudge laid on an exhibition of the Topographical Surveyors’ drawings, ‘not neglecting the Isle of Wight and Kent plans’. But aside from the triangulation, the Interior Survey’s techniques were not innovative, and replicated the standard methods of topographical surveying that had been used throughout the eighteenth century. The Trigonometrical Survey’s work was, however, in the vanguard of progress, and for this reason, the attention of the press and scientific community continued to be trained mainly on the primary triangulation.

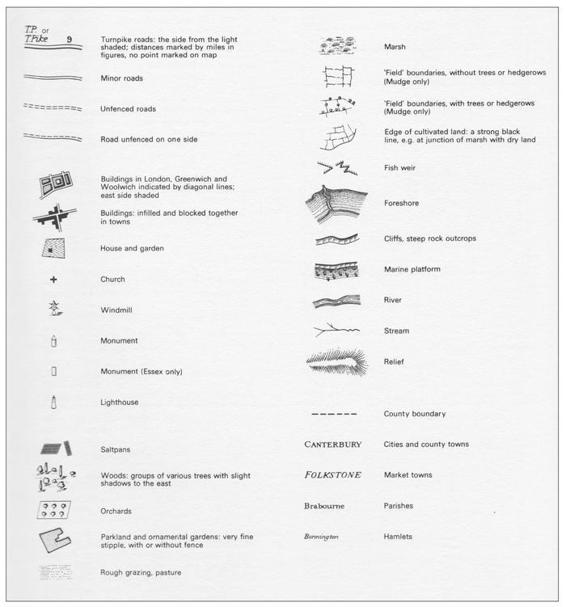

25. Although the Ordnance Survey’s early maps had no key to the symbols used, it has been possible to compile one.

Mudge always urged the necessity of putting the maps on public view. An advertisement for the surveys in 1818 acknowledged how ‘gentlemen’ were likely to want ‘to procure a map of the country surrounding their own

habitations

’. The public were able to obtain their long-awaited Ordnance Survey maps either from the Board of Ordnance’s headquarters in the Tower of London, or from William Faden’s premises at 6 Charing Cross. (After his death, Faden’s shop would pass to his apprentice James Wyld, and then to Edward Stanford. Stanford would go on to found the specialist map-retailer Stanford’s, which still flourishes today in nearby Long Acre.) As the

nineteenth

century progressed, the surveys could be procured from more and more map-sellers across Britain. Landowners who desired surveys of the area surrounding their estates could make an appointment at the Tower to peruse an index map from which they could select the relevant chart. The Tower and Faden’s shop both sold the first Ordnance Survey maps for three guineas (

£

3 3s) per county survey: the average weekly wage of one of the map’s engravers, or twenty days’ wages for a lesser craftsman. From this fee, set by the Board of Ordnance, Faden retained only half a guinea;

unsurprisingly

, he griped over this meagre commission. By 1816 the Ordnance Survey was charging

£

6 6s for its map of Devon, which spread over eight sheets: this was around forty days’ wages for a craftsman in the building trade.

The price tag mostly restricted access to the early Ordnance Survey maps to the social elite. There were exceptions, such as the Sheffield

warehouse

apprentice Joseph Hunter, who, in the spring of 1797, borrowed from

his local library John Aikin’s

Description of the Country from thirty to forty miles

around Manchester

and commented intelligently on its ‘excellent maps’. And Mudge donated many free copies of the Ordnance Survey’s maps to libraries, institutions and associations, through which less privileged members of

society

could witness the wonderful new cartographical productions. But in the main the consumption of maps in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the privilege of the affluent. Maps were expensive, and outside military circles it was primarily the upper classes who had been taught how to properly ‘read’ them. Map-reading is not an intuitive skill, and the language of contours and symbols needs to be acquired. An Ordnance Survey map-maker in the 1830s found that to describe his purpose to a local man in Ireland, he first needed to enquire, ‘Do you know what a

map

is?’ and to carefully explain that it was ‘a representation of the land on paper’.

Wealthy landowners bought the Ordnance Survey’s first maps, but at the small scale of one inch to one mile they had little practical utility to most and they are likely to have served instead as rhetorical images of power and ownership or as aesthetic artefacts. The kudos of the Ordnance Survey’s early maps was evident from an estate agent’s advertisement for the lease of Torbay House, in Paignton, Devon, in which the agent played up the fact that ‘the site is laid down in Mudge’s map of Devon’. For those who could afford the maps, an explicit mention of one’s property was evidently a powerful status symbol. The aristocratic affinity with cartography was borne out by the Scottish

nobleman

the 8th Earl of Wemyss, who had a pronounced penchant for maps and charts. He scrawled detailed annotations and corrections to the area around his estates all over his copy of John Armstrong Mostyn’s

Scotch Atlas

, not unlike map-readers today who make Ordnance Survey maps their own by scribbling routes, viewpoints, travel information, and even pub reviews onto their sheets.

In an era long before the advent of aeroplanes, the Ordnance Survey’s maps presented a vision of the nation from the perspective of someone elevated higher than the summits of Kent’s rolling hills. The only

contemporary

comparison was with the viewpoint of a traveller in a hot-air balloon. On 21 November 1783 the first manned hot-air balloon flight was made in a balloon constructed by Joseph and Jacques Montgolfier. The story goes that Joseph devised the conveyance as a possible reinforcement for the

French Army’s cavalry and infantry, an embryonic air force if you will. When early models proved successful at raising and carrying animals of various descriptions, Louis XVI agreed to the Montgolfiers’ suggestion that a crewed flight might be trialled. Two friends of the Montgolfier brothers, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes,

successfully

flew for twenty-five minutes from the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, five and a half miles south-east to the Butte-aux-Cailes, on the capital’s outskirts. Sadly Pilâtre de Rozier would become one of the first air fatalities when his balloon crashed during an attempted cross-Channel flight in June 1785.

On 15 September 1784 the aeronautical experiment was exported to Britain when an Italian, Vincenzo Lunardi, demonstrated a balloon flight from the Artillery Company’s grounds in London. Lunardi travelled

twenty-four

miles towards Standon Green End in Hertfordshire. His success spawned a frenzied craze for ballooning in England. Women’s skirts were decorated with balloons, bonnets were fashioned in the ‘Lunardi’ style (

balloon

-shaped, at a height of twenty-four inches), and a whole genre of ‘balloon literature’ appeared. Fanatics of the phenomenon earned the label ‘balloonatics’ and, at the outbreak of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, some Britons began to worry that the French Army might be developing a balloon division to conduct an invasion of England by air.

Many of the first authors of hot-air-ballooning literature described the delight of witnessing the British landscape from the air for the first time. Mrs Sage was the ‘first English female aerial traveller’, travelling in Lunardi’s

balloon

in June 1785. In her memoir of the landmark voyage, Sage recalled how, ‘in crossing over Westminster, we distinctly viewed every part of it; we hung some time over St James’s Park, and particularized almost every house we knew in Piccadilly’. This was pure voyeurism. Sage found that she could peek through the windows of the well-to-do, while their owners remained oblivious to her intrusion. When the balloon ‘turned on its axis’, she recalled how this ‘pleased us very much, as it presented the whole face of the

country

, in various points of view’. Sage’s pleasure was not so dissimilar to that of Google Earth and Google Street View users, who can simulate a flight across the earth’s digital representation, turning this way and that at will.

One balloonist compared his night-time ‘Balloon-Trip’ across the capital

to the experience of ‘looking down on an enormous map of London, with its suburbs to the east, north, and south, as far as the eye could reach, drawn in lines of fire!’ (referring to the city’s blazing street-lamps). A man called Thomas Baldwin composed ‘a narrative of a balloon excursion from Chester, the eighth of September 1785’, and he illustrated his text with views of the landscape below, which resembled maps overlain with clouds. If these balloonists imagined themselves to be flying over a map, then the Ordnance Survey’s first map-readers may, in turn, have felt themselves suddenly raised above their libraries or desks. Thus suspended miles above Kent, they were treated to a revelation of that county spread out below them, like the views hitherto reserved only for balloonatics.

C

HAPTER

S

EVEN

T

HE THREE ELEMENTS

of the Ordnance Survey – the Trigonometrical Survey, the Interior Survey and the engravers – worked in separate locations and at different speeds. While the Interior Surveyors busied themselves in the south-east and while the first Ordnance Survey map lay in the hands of its engravers, the Trigonometrical Survey’s operations were continuing

elsewhere

.

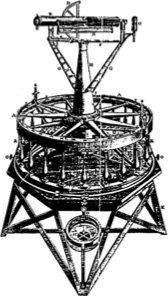

After he had finished triangulating Kent in 1795, William Mudge led his team into Dorset and Devon and then into the West Country and Cornwall. There were moments of intense wonderment in this part of the kingdom. While encamped in Britain’s south-westerly extremity, ‘making observations to determine the distance of the Scilly Isles from the Land’s End’, Mudge realised with joy that ‘the air was so unusually clear’ that he was able to

distinctly

make out through the theodolite’s telescope ‘soldiers at exercise in St Mary’s island’. And the strange effects of terrestrial refraction continued to plague and amuse the surveyors in equal measure. Whilst measuring from Pilsden Hill in Dorset towards Glastonbury Tor, a conical hill in Somerset topped with a roofless tower, Mudge was so proud of the Great Theodolite’s capacity to observe long distances ‘that, desirous of proving to a gentleman then with me in the observatory tent, the excellence of the telescope, I

desired him to apply his eye to it’. This visitor purred his admiration but when Mudge took back his toy and looked again through the sights, he explained how ‘the unusual distinctness of this object, led me to keep my eye a long time at the telescope’. ‘Whilst my attention was engaged,’ Mudge

continued

, ‘I perceived the top of the building

gradually

rise above the micrometer wire, and so continue to do, till it was elevated [far] above its first apparent situation; it then remained stationary,’ he concluded, baffled. Terrestrial refraction meant that the air was turned into a prism, by which rays of light were bent to produce these strange hallucinatory effects.