Map of a Nation (27 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

Mudge and Dalby duly spent much of 1793 on the south coast of England, in East and West Sussex. They got drenched and frustrated in the Isle of Wight, where astronomical measurements to find the precise directions of north and south were thwarted by consistent fog. They also encountered a weird phenomenon known as ‘terrestrial refraction’, in which the

atmosphere

acted as a prism and bent rays of light to produce mirages. Strolling around the Isle of Wight, Dalby noticed that the top of a faraway hill ‘seemed to dance up and down in a very extraordinary manner’. He described how, ‘when the eye was brought to about 2 feet from the ground, the top of the hill appeared totally detached, or lifted up from the lower part, for the sky was seen under it’. And that same summer the surveyors also camped at Beachy Head, the perilously high chalk cliff in East Sussex. Fourteen years later, the poet Charlotte Smith described the awe-inspiring view from its summit:

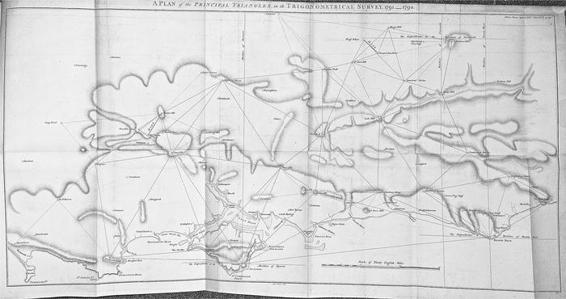

23. The ‘Principal Triangles’ measured during the first three years of the Ordnance Survey, between 1791 and 1794.

… how wide the view!

Till in the distant north it melts away,

And mingles indiscriminate with clouds:

But if the eye could reach so far, the mart

Of England’s capital, its domes and spires

Might be perceived – Yet hence the distant range

Of Kentish hills, appear in purple haze;

And nearer, undulate the wooded heights,

And airy summits, that above the mole

Rise in green beauty; and the beacon’d ridge

Of Black-down shagg’d with heath, and swelling rude

Like a dark island from the vale …

Mudge and Dalby’s time at Beachy Head was not without incident. Whilst encamped one night, they ‘had the mortification to hear plainly the cries of the poor English sailors’ on a ship below the cliff as they were boarded and attacked by passing French pirates. ‘For want of cannon’, possessing merely telescopes and compasses, and poised 530 feet above the sea, the surveyors could only listen in impotent horror.

By the end of 1793’s surveying season, Mudge and Dalby had completed the Trigonometrical Survey of Sussex. Responsibility for the creation of the map now lay with the Tower draughtsmen. The co-director of the original ‘Great Map’ of Sussex, Thomas Yeakell, was deceased, but its surviving author, William Gardner, selected Thomas Gream, who was also from the Tower Drawing Room, to assist him. Gardner and Gream ‘filled in’ Mudge and Dalby’s primary triangulation by observing a network of smaller

triangles

between trig points such as church spires or the turrets of stately homes with a much smaller and less sophisticated theodolite. They even used the ‘north-west chimney’ of Lennox’s mansion at Goodwood, which possessed its own observatory, as one of these secondary triangulation stations. Then the pair traced the course of Sussex’s major roads and rivers, using roughly the same ‘traverse’ methodology that William Roy had adopted half a

century

previously in Scotland. The small theodolite was used to place features and landmarks, such as forests and buildings, that punctuated the

intervening

land between these networks.

Gardner and Gream’s map of Sussex was published commercially by the Royal Geographer William Faden in 1795, with a dedication to Charles Lennox. In black and white and on a scale of an inch to a mile, the map showed the gentle undulations of the Sussex coastline in twisting lines of black hachures that in some places could look as if a series of small furry caterpillars had fallen asleep on the sheet. The depiction of the prickly groundcover of gorse was almost tangible, shown by clumps of tiny vertical lines interspersed with the occasional dark knot of scrub. The forests north of Rotherfield were represented by black segments of miniature trees, whose dense clustering evoked the claustrophobia of the woods themselves. A neat mosaic of fields sprawled over the intervening land: a vision of order and harmony.

As the first joint production of the Trigonometrical Survey with another team of Ordnance map-makers, this survey is a contender for the accolade of the ‘first Ordnance Survey map’, and Mudge and Williams lauded the ‘Survey of Sussex’ as one of ‘the only maps which have passed under our notice, worthy [of] commendation’. However, at this stage there was no long-term scheme to create a series of county maps of the whole nation from a formal collaboration of the Trigonometrical Survey with the Ordnance’s draughtsmen. The Sussex survey was therefore chiefly celebrated then and since as a unique event, albeit a particularly accomplished one, but not as the first of the Ordnance Survey’s First Series of maps.

A

FTER THE COMPLETION

of the triangulation across Sussex, William Mudge wanted to take the Trigonometrical Survey west through Hampshire, Devon, Somerset and Cornwall, still concentrating on the coast and the land that led from it to London. He started to keep his eyes open for a new site that would act as a ‘base of verification’. A second baseline in south-west Britain would check the accuracy of the triangles that had already been observed. It would also act as a reliable foundation for future series of

triangles

that were to cascade into the West Country and Wales.

But a suitable site proved elusive. Mudge visited Longham Common near Poole in Dorset, but the stretch of land was too populated with obstacles such as barns, stables and outbuildings to be freely measured. He also trekked to King’s Sedgemoor, a peat basin in the centre of Somerset, where the baseline for the very first British triangulation had been measured in 1681. But the land had recently come under an Enclosure Act by which it was being drained and then perhaps partitioned and cultivated. Over a period of about seventy-five years, England’s landscape was redrawn through such legislation. Although it had been a legal phenomenon since the early modern period, ‘enclosure’ accelerated between the second quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Previously labourers had enjoyed traditional mowing and grazing rights over pieces of common land, even if they were

owned by another person, and the ‘open field system’ gave over four very large unfenced fields per manor or village to labouring families to farm in strips. But the Enclosure Acts consolidated these farmed strips and pieces of common land into fields that were privately owned by landlords, thus creating England’s present-day patchwork landscape of agriculture. Over six million acres of English soil were ‘enclosed’ in the eighteenth century, and one historian has described how the hedges and fences that demarcated the new distribution of land became ‘the symbols of the new England’.

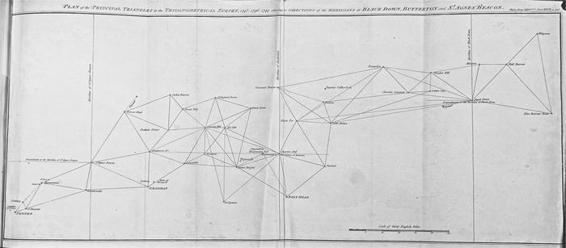

24. The progress of the Ordnance Survey’s triangulation into the West Country and Cornwall.

These Acts created a landless working class, many of whom would migrate to cities to work in the new factories and mills once England started

industrialising

. Enclosure was a hugely contentious subject. Many sympathised with the rural labourers whose mental maps of their surroundings were forced to change overnight. The agricultural reformer Arthur Young imagined a poor man’s account of Enclosure: ‘All I know is, I had a cow and Parliament took it from me.’ But Young also despised what he saw as the dreadful waste of unenclosed common land. Referring to King’s Sedgemoor

before its enclosure, he lamented: ‘what a disgrace to the whole nation it is, to have 11,520 such acres to lie waste in a kingdom that is quarrelling about high prices of provisions!’ Young claimed that the land was ‘so rich, that some sensible farmers assured me it wanted nothing but draining to be made well worth from 20 shillings to 25 shillings an acre on average’. But Young’s priorities were not the same as Mudge’s. When King’s Sedgemoor was eventually enclosed in the 1790s, the ‘improvers’ and drainers who

scuttled

over its surface rendered the tract of land utterly impracticable for a baseline.

Another site whose ‘wastefulness’ Young bemoaned turned out to be just the place Mudge was looking for. In the late 1760s, Young had complained that ‘such a vast tract of uncultivated land’ as Salisbury Plain is ‘a public nuisance’. Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau that covers 300 square miles of Wiltshire and Hampshire, and Young suggested: ‘what an amazing improvement would it be to cut this vast plain into farms, by inclosure of quick hedges, with portions planted with such trees as best suit the soil! A very different aspect the country would present from what it does at present, without a hedge, tree or hut; and inhabited by only a few shepherds and their flocks.’ But Young’s vision had not been realised and Salisbury’s Plain’s unenclosed stretches of flat heathland, and sparse population, offered an ideal site for the Ordnance Survey’s ‘base of verification’. So in July 1793, Mudge and Dalby travelled to Salisbury Plain to select the ends of their new baseline. For its southern extremity, they lighted on a spot near Old Sarum, an Iron Age hill fort marking the earliest settlement of Salisbury. The baseline then stretched over seven miles north-north-east to Beacon Hill, whose summit provided a ‘commanding view’ of almost the whole baseline.

During that same summer, the poet William Wordsworth spent two days wandering on foot over Salisbury Plain and he described how, ‘though

cultivation

was then widely spread through parts of it’, the land ‘had upon the whole a still more impressive appearance’. Returning from Portsmouth where Britain’s naval fleets were busy preparing for battle with

revolutionary

France, Wordsworth was full of ‘melancholy forebodings’ and predicted the war’s ‘long continuance’ and its inevitable ‘distress and

misery beyond all possible calculation’. Perceiving Britain’s decision to go to war with France as a betrayal of the Glorious Revolution’s legacy and the French Revolution’s republican spirit, Wordsworth began to feel that the landscape itself was reflecting his sense of gloom and alienation from his fellow Britons in the current climate of martial bonhomie. In his

ensuing

poem, ‘Guilt and Sorrow, or Incidents upon Salisbury Plain’, Wordsworth imagined a sailor returning from war, reduced to vagrancy and dressed in a tattered red uniform. He pictured this man, as friendless and homeless as the poet felt himself to be, wandering disconsolately over the plateau. A distant church spire initially fixed the sailor’s eye like an emotional trig point, but as ‘gathering clouds grew red with storming fire’, it soon disappeared ‘in the blank sky’. And ‘a naked guide-post’s double head’, which the sailor glimpsed in a flash of lightning, provided only a momentary ‘gleam of pleasure’. Thanks to the Ordnance Survey, Salisbury Plain would become integral to the history of Britons’ attempts to orient themselves, but for Wordsworth it stood for alienation and

disorientation

.