Map of a Nation (19 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

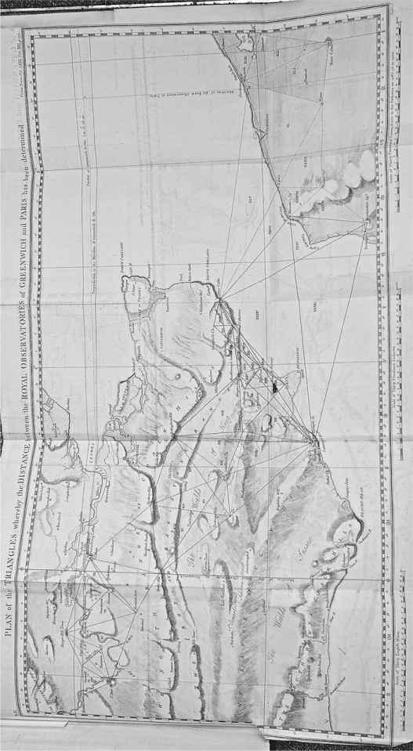

17. Map of the triangles measured during the Anglo-French collaboration of the 1780s.

By mid October the cross-Channel observations were complete and Britain and France had been trigonometrically bonded. The exercise acted as a double-check on the accuracy of the triangulation that underpinned the

Carte de Cassini

and it also allowed the relative merits of the French repeating circle and the British theodolite to be compared. Both were found to

measure

angles with similar precision, to within a couple of seconds of the truth. Roy’s team now needed to complete the half-finished triangulation

extending

from Hounslow Heath down to the coast. But first he decided to measure a second baseline, known as a ‘base of verification’. The actual measurement of this second base on the ground could be compared with the length

provided

by trigonometrical equations to test the accuracy of the triangulation so far and expose any errors. In August 1787 Roy and his assistants headed to Romney Marsh, a flat stretch of wetland just inland from the south coast of Kent and East Sussex, sheltered by the shingle beach of Dungeness (now

home to a nuclear power station). Roy explained that ‘from its levelness, as well as other advantageous circumstances attending its situation’, Romney Marsh ‘seem[ed] to me to afford the best base of verification for the last

triangle

’. But the soggy ground was ‘so much intersected with ditches full of water’ that ‘the laying of bridges for the tripod stands’ (for the glass rods) was ‘a very troublesome and tedious operation’. Despite these hazards, the Romney Marsh measurement was a success. It gave a distance of 28,532.92 feet and showed that Roy’s triangulation was extraordinarily accurate. As an impressed journalist reported, ‘the

line of verification

, measured for that

purpose

on

Romney marsh

’ showed that ‘there was only an errour of

four inches and

a half

’ between the actual measurement of the base and that calculated by trigonometric equations from the theodolite’s angular observations.

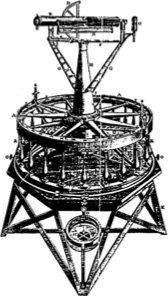

The task now for Roy and his assistants was to finish the triangulation from London to the south coast. As they hopped through Kent, local onlookers were intrigued by the Scottish surveyor hoisting his strange squat apparatus up churches, castles and hills, and the flashing lights on the horizon that accompanied its appearance. One Kentish man described in wonderment: ‘as I passed through Tenterden, I observed a kind of tent on the top of the steeple, and on enquiry was informed that General Roy … and a party of the Artillery from Woolwich, with a large instrument made by Ramsden, were making observations of distant objects’. ‘I know there was a

measurement

on Hounslow-heath two or three years ago,’ he continued, ‘but what connection it can have with signals; or what is the purport of those signals, I cannot imagine.’

Soon the nights closed in, the light faded, the temperature plummeted and the triangulation had to be suspended for another year. The short days and muted light of winter made long-distance observations impossible and Roy had to wait to fill in the few remaining pieces of the jigsaw puzzle until August 1788 – which would turn out to be this map-maker’s last surveying fling. Once the observations were complete, Roy spent the remainder of the year and the beginning of the next making sense of his calculations. The French wrote up and published their side of the story in 1790. Roy crafted his experiences and calculations into two lengthy articles for the Royal Society’s journal, the

Philosophical Transactions

. He calculated that the longitudinal separation between

the two observatories at Paris and Greenwich amounted to a time difference of nine minutes and nineteen seconds. (The sun moves around the globe, passing through the imaginary lines of longitude at a rate of fifteen degrees per hour.) Although Maskelyne’s secret experiment to measure this distance had actually come up with something very similar (nine minutes and twenty seconds), in a rather devious twist Roy misrepresented the Astronomer Royal’s calculations of Greenwich’s longitude in one of his articles as nine minutes and 30.5 seconds, presumably in order to prove the superior worth of the triangulation over astronomy and to demonstrate the value of the Paris–Greenwich connection in finding the true position of England’s royal observatory. Importantly, Roy’s results largely agreed with those of the French astronomers. The two parties’ measurements of the twenty-six-mile distance between Dover Castle and Notre Dame’s spire at Calais differed by only seven feet. This accord confirmed the accuracy of the teams’ triangulations and the precision of their instruments. Compared with modern GPS data, the results of the Anglo-French collaboration are not spot-on, but in the 1780s the accuracy of the project’s methods and instruments seemed miraculous.

Observers of the operation were given little choice but to regard it as a

triumph

of accuracy. ‘Truth’ was a particularly favourite word of Roy’s, who hammered home ‘the last exactness’ and ‘mathematical exactness’ of his

calculations

and lauded the ‘extremely perfect’ instruments that had been used. He also showed a passionate allegiance to decimal points, although it was an inconsistent one: some calculations were shown to four decimal places, others to one or two. Roy’s enthusiastic conviction of the accuracy of his work was infectious. Journalists repeated the claims that ‘the accuracy of this operation is very considerable’ and that the Paris–Greenwich triangulation was ‘

conducted

in a manner which confers the highest honour on the abilities and attention of major-general Roy’. A writer for the

St James’s Chronicle

wrote that ‘among the improvements of the present age, may be reckoned, the extreme nicety in the construction of mathematical instruments, and the wonderful accuracy of trigonometrical mensuration’, and he concluded that Roy’s

operation

‘was prosecuted, at every step, with niceness of observation and accuracy of calculation’. Another journalist claimed that ‘no measurement of a similar kind has hitherto, we believe, been carried on with so much accuracy’.

The Anglo-French venture seemed to have realised the highest ideal of the Enlightenment: perfect measurement of the ground beneath our feet. William Roy came to be popularly regarded as the embodiment of the ‘Enlightenment method’. When the accuracy of Murdoch Mackenzie Sr’s

Nautical Survey of the Orkney Islands and Hebrides

, which was based on maps made in the 1770s, came under fire, its ‘uniform agree[ment]’ with Roy’s much earlier Military Survey of Scotland seemed an incontrovertible

settlement

of the debate in Mackenzie’s favour, despite the obvious flaws of the earlier work. Credit for William Calderwood’s glass measuring rods was sometimes given to Roy instead, who was thought to have ‘invented an instrument, that from the materials of which it is composed is not subject to any variation whatever’. The supposedly supreme accuracy of Roy’s

triangulation

also became a patriotic weapon. The

New Annual Register

called the triangulation ‘a national work of great importance’ and the astronomer Francis Wollaston felt it ‘may be considered in some sort as a national

concern

’. They both based their patriotic pride on the truth and accuracy of Roy’s instruments and methods. Rather than celebrate the enterprise for the amicability between the French and British surveying parties, most people in Britain, including Roy himself, seem to have been more interested in the project for its national merits.

And yet all this remarkable acclaim was not quite enough to satisfy William Roy. As he aged, his reticence turned to grouchiness. The delay that Jesse Ramsden had inflicted on the Paris–Greenwich triangulation gnawed away at him. ‘No consideration upon earth would ever make me go through the same or such another operation again, merely from the drudgery of having to do with such a Man!’, he fumed to Banks. Roy vented his rage in his last article for the

Philosophical Transactions

, where he accused Ramsden of

intentional

negligence and sloppy workmanship, and elsewhere of being ‘too remiss and dilatory’. Blissfully ignorant of the contents of Roy’s article, the equanimous Ramsden was in the audience when it was first read aloud before the Royal Society. ‘Nothing could equal my surprize on hearing the charges brought against me, and misrepresentations contained in [the] paper,’ Ramsden exclaimed. ‘I was the more affected by it as coming from a Gentleman with whom I considered myself in Friendship, and, who had

many obligations to me for my assistance.’ In an open letter to the Royal Society, Ramsden tackled Roy’s charges one by one. He accused him of ‘unskilfulness’ in the handling of the theodolite, and demanded that it be acknowledged ‘that every part of the Instrument and Apparatus is of my invention’.

Roy’s cantankerousness may have been due to his failing health, caused by chronic lung disease. In the spring of 1789 he was forced to retreat to the mountains of North Wales to convalesce. Although temporarily better, by winter he was much worse again and started to suffer frightening episodes of spitting blood. At the close of the Paris–Greenwich triangulation, Roy made an extended visit to Lisbon to recuperate from the toll the project had had on his well-being. Feeling much better, he returned to London in the spring of 1790 and applied himself to writing an ‘Account of the Trigonometrical Operations by which the Distance between the Meridians of the Royal Observatories of Greenwich and Paris has been determined’.

On 30 June 1790 Roy spent the afternoon at the War Office before

returning

home to correct the proofs for his article. Whilst hunched over his desk, pen in hand, he suffered a sudden seizure at nine o’clock in the evening. In the early hours of 1 July William Roy died, at the age of sixty-four. The news spread quickly throughout Britain’s military and scientific elite. Five days after his death

The Times

mourned that ‘the Republic of Letters will

experience

a great loss in the death of General Roy. As a draughtsman, his pencil was universally admired [and] he was a great favourite with his Majesty.’ This innovative, imaginative man, who had transformed the fields of

military

map-making and geodesy in Britain and appeared to have realised the Enlightenment’s ideal of creating a perfectly truthful image of the natural world, had died without seeing his life’s ambition realised: the creation of a complete, accurate, national survey. But the Paris–Greenwich triangulation had laid the groundwork, and many would later consider it as the true antecedent of that map.

1

‘It is interesting for the progress of astronomy that we should know the exact difference between the longitude and latitude of the two most famous observatories of Europe.’

2

‘General Roy is at some distance from London … but from what I hear, he has not reached very far yet.’

C

HAPTER

F

OUR