Map of a Nation (17 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

On 16 April 1784 preparations for the baseline measurement got under way. Assisted by Banks and Blagden, Roy first made a reconnaissance,

identifying

a dead-straight tract extending across almost the whole Heath. Its south-western extremity was on the site of Hampton Poor House, now long gone. (In its place, amid the leafier, prettier end of the old Hounslow Heath, only a couple of miles from Hampton Court Palace, there is instead a memorial to Roy, a small cul-de-sac named Roy Grove and a plaque

celebrating

his achievements.) The base then extended just ‘upwards of five miles’ to the north-west, to a small settlement once known as King’s Arbour, which has been swallowed up by the world’s second busiest airport. Roy marked the baseline’s ends with wooden pipes that he drove deeply into the ground and which he hoped would form permanent markers.

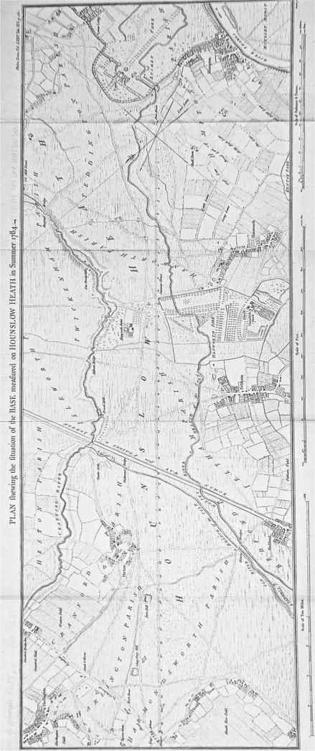

14. ‘Plan Shewing the Situation of the Base Measured on Hounslow Heath in Summer 1784’.

In appointing William Roy to direct the British side of the Paris–Greenwich triangulation, Joseph Banks and the Royal Society benefited from his military affiliations. Instead of hiring ‘country labourers’, Roy found trained and ‘attentive’ soldiers to assist the measurement. Their job was to clear ‘a narrow tract along the heath’ to ‘permit the base to be accurately traced out thereon’. But the soldiers found themselves stumbling through brushwood and thick brambles, and coming dangerously close to ‘certain ponds, or gravel-pits full of water’. Through this unpredictable landscape, they had to pick out a length of five miles that was entirely free of such obstacles. The summer of 1783 had been unusually hot and dry, but that of 1784 was distinguished by ‘extreme wetness’, in Roy’s words. The soldiers sat up all night through

torrential downpours, ‘guarding such parts of the apparatus’ against thieves and grazing cattle.

On 16 June the base measurement began. Roy first conducted a ‘rough’ survey of the distance with a 100-foot steel chain that weighed eighteen pounds, laying it along the space that had been cleared by his soldiers. But the accurate determination of the base’s length was to take place with wooden measuring rods. These were dowels of, in this case, deal or Scots pine, which extended to twenty feet and rested on stands, 2 foot 7 inches high. From a side view, the instruments resembled suspension bridges, with an elaborate network of supports above and on either side of the central rods to prevent them from buckling. The day, 15 July 1784, that these deal rods arrived from the instrument-maker Jesse Ramsden’s workshop was momentous. Joseph Banks hurried to the southern end of the baseline, accompanied by Blagden and three other eminent Royal Society fellows. Ever the charming host, Banks ordered tents to be pitched nearby, where Roy recorded in wonderment that visitors to the site ‘met with the most

hospitable

supply of every necessary and even elegant refreshment’.

The baseline measurement began when Roy placed the first rod at the base’s end at Hampton Poor House, and arranged it to coincide with the direction of the roughly traced base. He had found rods measuring between twenty-five and thirty feet to be ‘rather too unwieldy’, and it is likely that the twenty-foot rods were also initially tricky to position in a straight line, and perhaps liable to tip over too. Roy gradually shifted a second rod into

alignment

, end to end, with the first. Once this second rod was firmly stabilised on the ground, the first could then be detached and brought round to the front of the second, where it was again placed nose to nose. Carefully noting the number of times he alternated the rods, Roy inched along the length of the baseline, hoping to produce the most accurate assessment possible of that stretch of land. It took five hours to measure a ‘short distance of 300 feet’, the length of only fifteen rods.

Despite the initial excitement surrounding the commencement of the base measurement, Roy quickly became troubled. The incessant rain and

humidity

of that summer wreaked havoc with the wooden measuring rods; they expanded and warped so much as to become almost unusable. Depressed

and disappointed, Roy was at a loss, fed up with the relentless rain and

perhaps

beginning to question whether a man almost sixty years old should be exposing himself to the elements in this way. But he rallied when a young friend from his days in Scotland, William Calderwood, who was assisting the baseline measurement, hit upon a solution: rods made of glass. After a brief delay to allow Ramsden to construct these new instruments, the base

measurement

began again at 8.30 a.m. on 2 August. Calderwood’s rods acquitted themselves well. Roy delightedly found them to be ‘so straight that, when laid on a table, the eye, placed at one end looking through them, could see any small object in the axis of the bore at the other end’.

On 30 August the baseline measurement was finished, after seventy-five consecutive days on the Heath. The sight of a group of uniformed soldiers manoeuvring strange, twenty-foot glass rods around the brambles and pools of the Heath must have bemused passing tradesmen and the homeless people who congregated around Hampton Poor House. And the night-time glow of the soldiers’ encampment may have temporarily deterred the Heath’s highwaymen from their illegal pursuits. The baseline measurement was also cause for the arrival of more salubrious guests from further afield. Due to the sophistication of Roy’s techniques and the political significance of this Anglo-French collaboration, many eager voyeurs flocked to the event on Hounslow Heath, especially on its first and last days. Journalists for national newspapers reported Roy’s valiant ‘undertaking’. The frenzy came to a head on 21 August when King George III and his entourage paid a visit. (They had delayed it from 19 July, a day that experienced exceptionally heavy rain.) The King stayed for ‘the space of two hours, entering very minutely into the mode of conducting [the measurement], which met with his gracious approbation’. The

St James’s Chronicle

reported George III’s encouragement of the Paris–Greenwich triangulation in admiring terms, praising ‘his Majesty (who is ever ready to patronise useful Schemes)’. In the wake of the American War of Independence that had seen the King

publicly

vilified for his intransigent refusal to be reconciled with the rebellious colonists, this approval must have been a pleasant novelty for him.

The final moments on the Heath lived up to the hype of the previous days. A host of excited celebrities flocked to the baseline to celebrate Roy’s

achievement, including the art collector Sir William Hamilton, the

mineralogist

Charles Francis Greville (who was then the lover of Emma Hamilton, later Nelson’s mistress), the Scottish physician and military engineer Charles Bisset, and Trinity College Dublin’s astronomy professor, the Reverend Dr Henry Usher. The urbane figure of Joseph Banks, who had given ‘his

attendance

from morning to night in the field, during the whole progress of the work’, presided over the closing festivities. When the party broke up the

following

day, Banks took the wooden and glass rods back to his house. Roy disappeared, to calculate the baseline’s length. He found it to be 27,404.7 feet long (5.190 miles). Compared with its modern GPS-defined distance of 27,376.8 feet (5.185 miles), and taking into account the limitations of his time, Roy’s baseline measurement was astonishingly accurate. He himself stated proudly that ‘there never has been so great a proportion of the surface of the Earth measured with so much care & accuracy’.

N

OW THAT THE

baseline had been measured, the triangulation could begin. From his first perusal of Cassini de Thury’s memorandum back in 1783, William Roy had realised that the proposed connection between Paris and Greenwich required surveying apparatus far more accurate than any currently in existence. Over the Channel, French surveyors extolled the merits of a new instrument called a ‘repeating circle’. Constructed from two telescopes fixed to a circular scale, the repeating circle worked by taking

multiple

observations of angles on different parts of the scale and averaging these out to produce a single accurate measurement. But the British were proud of the theodolite, their national instrument, and refused to adopt this foreign innovation. So in 1784 Roy approached Jesse Ramsden and placed an order for the most sophisticated theodolite in the world.

Ramsden was an innkeeper’s son, born near Halifax in Yorkshire, who had risen from modest beginnings to become the most sought-after

mathematical

-instrument-maker in London. It was an exciting time to be involved in the design and creation of such apparatus. Before the mid eighteenth century, it

was unusual for surveying instruments such as theodolites to incorporate

telescopic

lenses, which were dogged by ‘chromatic aberration’, giving rise to distracting coronas of colour that clung to major outlines. But in 1757 John Dollond, the son of a Huguenot silk-weaver and one of the founders of the still extant opticians Dolland [

sic

] & Aitchison, reinvented telescope technology by patenting an ‘achromatic lens’ which limited this irritating

phenomenon

. By fixing a convex to a concave lens of differing materials, Dollond’s device brought wavelengths of colour to a single focal point, thus eliminating the coronas that had been caused by the divergence of these waves. Although he was not the first person to invent the achromatic lens, Dollond’s patent made him a very wealthy and famous craftsman. The lens revolutionised the worlds of mathematical instrument-making and surveying, and allowed map-makers to see further and more distinctly than ever before.

In 1766 Ramsden married Dollond’s youngest daughter, and worked alongside his father-in-law for the next seven years. In 1773 Ramsden set up his own premises on Piccadilly, ‘at the Sign of the Golden Spectacles’. The following year, in this busy workshop at the heart of London’s

fashionable

West End, he perfected a machine called a ‘dividing engine’ that engraved scales, such as degrees of an angle or inches in length, onto

instruments

more minutely than almost any in existence. A circle can be divided into 360 degrees, each degree is subdivided into sixty minutes, and each minute into sixty seconds. Back in the seventeenth century, the natural philosopher Robert Hooke had surmised that the average human eye could not properly distinguish any angular divisions smaller than around one ‘minute of arc’, a sixtieth of a degree. If the scale was any more minute, Hooke suggested that the eye became dizzy and unable to read the precise value of the angle. But Ramsden’s ‘dividing engine’ engraved instruments with scales that measured angles to one

second

of arc, a 3600th of a degree. These tiny divisions could only be read with the help of a ‘micrometer’: a device that had been invented in the 1640s by the instrument-maker William Gascoigne and which amplified the most minute divisions of the scale to a level comprehendable by the eye by means of a screw. Thanks to the

unprecedented

precision of Ramsden’s instruments, astronomers, mathematicians, geodesists and map-makers flocked from all over Europe to buy and

commission apparatus from his workshop. Ramsden’s innovating

imagination

and consummate skill set him leagues apart from his colleagues.

Ramsden was a good-natured man, said to be ‘full of intelligence and sweetness’. When Roy approached him in 1784, the instrument-maker was about to turn fifty. He was said by the diplomat and writer Louis Dutens to possess ‘an expression of cheerfulness and a smile the playful benevolence of which will not easily be forgotten by his friends. His whole manner had a character of frankness and good humour which he well knew to be

irresistible

.’ Eight years his elder, Roy was of a very different temperament: serious, reticent, but every bit as much of a perfectionist. One fatal flaw in Ramsden’s character would set the two at loggerheads. Ramsden was late for almost everything. His insistence on perfection meant that instruments were kept at his warehouse for years beyond their deadline, while he tinkered and refined. One client commented crossly that ‘there are few lively persons with such an open countenance as Ramsden, but one can also say that not withstanding this same countenance he has no scruples about failing to meet his promises’. There is an apocryphal story that when summoned to attend George III, Ramsden was chided by that monarch that, while he was ‘

punctual

as to the day and the hour’ he was ‘late by a whole year’. When Roy commissioned Ramsden to make ‘the best Instrument [he] could within a limited price, for measuring horizontal angles’, the instrument-maker saw this as a thrilling opportunity to produce a theodolite that ‘might be

rendered

superior in point of accuracy to any thing of whatever radius yet made if the expence necessarily incurred could be allowed’. Enthused by Ramsden’s eagerness, Roy and Banks agreed to meet the costs. But they were not prepared for the toll in time.