Map of a Nation (8 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

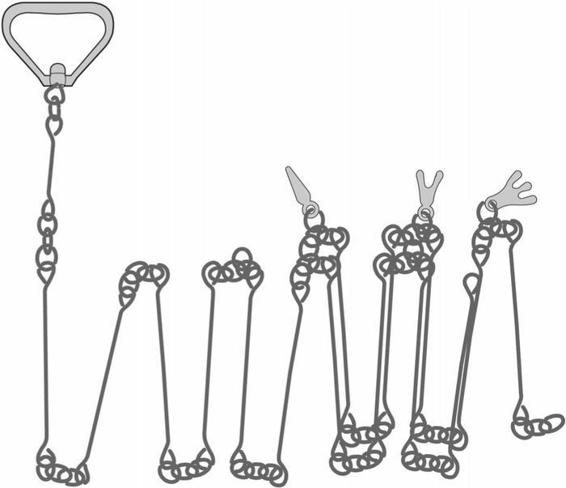

6. Gunter’s chain.

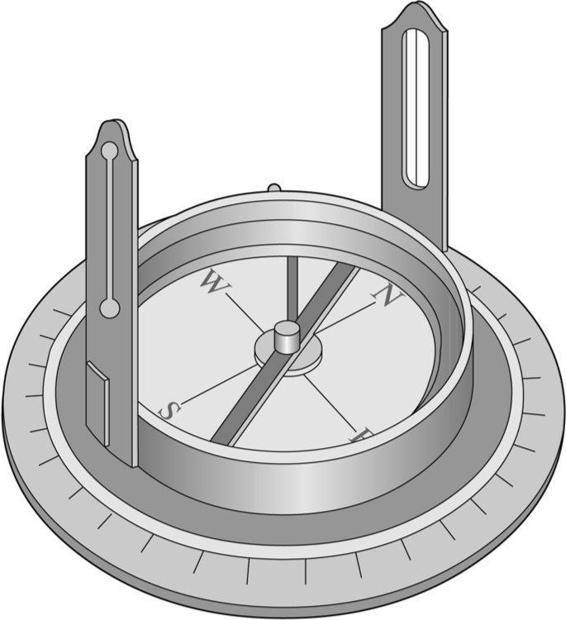

Roy needed to measure the angles as well as the lengths of the roads’ twists and turns, and for this he cradled in his hands a simple version of a

theodolite

. Invented in England by a Kentish mathematician called Digges in the second half of the sixteenth century, the theodolite didn’t make its way onto the Continent until the nineteenth century. Its birthplace was important to British surveyors; many thought of it as their national instrument. The

word’s etymology is hazy, but it may have derived from two Greek words meaning ‘I view’ and ‘clearly visible’. Digges had described his

theodelitus

as ‘a circle divided into 360 degrees’, which was attached to ‘sights’. Roy’s theodolite was a type called a

circumferentor

and consisted of an alidade fixed to a compass; like most theodolites in the first half of the eighteenth century, it did not contain a telescope. The instrument exploited the principle that light travels in a straight line in order to measure the angle of a surveyor’s sight line from landmark to landmark.

7. A circumferentor.

Standing at the first staff that he had thrust into the ground, Roy placed his circumferentor on a tripod by its side. He then crouched down to bring his head to the instrument’s level, closed one eye and placed the open one before the nearest vane of the alidade. Rotating the circumferentor’s compass slowly with his left hand (it has been suggested that Roy was left-handed), he brought into view the second surveying staff, which was positioned at the nearest bend in the road, until its width filled the tiny slit of the alidade’s furthest vane. Roy fixed the circumferentor at this position, straightened up and read the angle of his sight line off the instrument’s compass. Jotting the angle and distance that separated the two staffs in a notebook, accompanied by a quick sketch, Roy then repeated the whole process. He pulled the first

staff out of the ground and walked to the second bend in the road, where he plunged it into a new spot. Then, with the chain and circumferentor, he measured the distance and the angle of this second segment. Roy followed this method over and over, until he had surveyed the entire thirty-mile stretch between Fort Augustus and Inverness. But there was no rest. He also turned his attention to the slightly shorter distance that separated Fort Augustus from Fort William, and to the precipitous roads that fingered south-east towards Blair Atholl, Dunkeld and Perth. When Roy had finished mapping the Highlands’ military roads, he applied the same technique to its major rivers. His task was to piece together a dense skeleton of the multiple networks that traversed the Highland landscape, as the basis for a new national map.

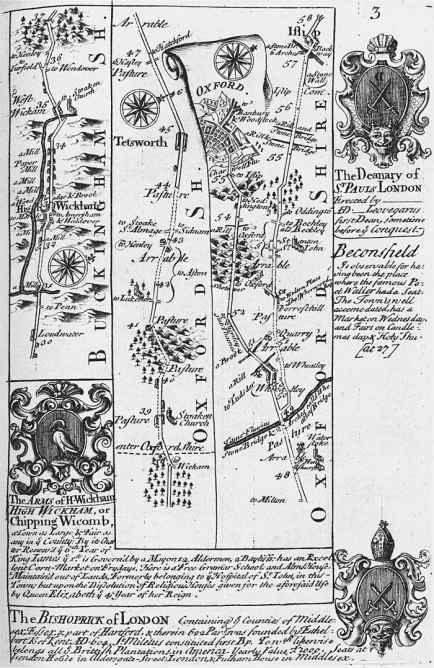

8. An extract from John Ogilby’s

Britannia Depicta,

1720,

shows a ‘strip map’ or ‘route survey’ of the main road and surrounding territory between High Wycombe and

Oxford.

Roy’s attention was not only trained on the roads and rivers that stretched before him. An array of landmarks clustered on either side of both, such as drovers’ paths, crofts and the outer walls of large private estates. He selected the most prominent of those that were visible from the road, and measured compass bearings to them with his circumferentor. But instead of measuring with the chain, which would have been excrutiatingly time-consuming and difficult, due to the rugged terrain, he largely guessed at their proximity and duly positioned a smattering of features around the networks of waterways and highways that were marked on his sketch map. He also located visible mountains and lochs with his circumferentor and sketched in their rough outline by sight. The technique that Roy was using throughout the Military Survey was widely known as ‘traverse’ or ‘route’ surveying. It had been famously employed by the publisher and cosmographer John Ogilby in 1675 in his

Britannia Depicta

, which was ‘an illustration of the kingdom of England and dominion of Wales: by a geographical and historical description of the roads thereof’. After measuring the roads of England and Wales using a ‘great wheel’ or perambulator, Ogilby had drawn a hundred ‘strip maps’ or traverse surveys, delineating the distances and nearby attractions of 2519 miles of road. But maps like Ogilby’s risked giving their users tunnel vision, training readers’ eyes solely on the road ahead and its closest landmarks. Roy’s traverse surveys for the Military Survey were also focused primarily on the course of Scotland’s major networks of rivers and thoroughfares, but he took in much of the intervening land too, even if only in a rather hazy

fashion, and his resulting surveys offered a far more expansive and coherent map of a nation than Ogilby’s strip maps.

Ideally, traverse surveys would be conducted by groups: one man would carry the theodolite, two measured with the chain, two held the staffs, one made the observation and another acted as attendant. It is nearly impossible to do all this alone. William Roy must have had assistants, but it seems that initially he was the only trained map-maker on this mission to measure some of the most exposed and unforgiving corners of the Scottish landscape. The rugged scenery over which the young man trudged made his task extremely taxing. Wade’s roads were breathtaking feats of engineering: they leapt up and over some of the highest passes and sharpest descents in the country and penetrated far into the Jacobites’ heartlands. At times, Roy must have felt perilously vulnerable. He was likely to have been the victim of battering rain-storms, fierce winds, exhausting summits and a niggling terror that, behind his back, a host of hostile Jacobites might be gathering.

Twenty-six

years after Roy had first laid his measuring chain along the road from Fort Augustus to Inverness, the lexicographer and polymath Samuel Johnson followed in his footsteps on ‘a journey to the Western Islands of Scotland’. Struggling on horseback up a precipitous series of hairpin bends in the road, Johnson cried out that ‘to make this way … might have broken the perseverance of a Roman legion’.

Hostility from the locals may have added to Roy’s woes. Map-makers were frequently an unwelcome presence in the Highlands, as many of the indigenous population assumed, often with reason, that they were tools of the state, surveying the land for purposes of taxation or surveillance. In the early 1740s, the Perthshire hydrographer Alexander Bryce had been engaged in mapping the north-west coast of Scotland between Assynt and Caithness for his

Map of the north coast of Britain.

But some smugglers were

suspicious

of his close attention to the region’s harbours and bays, worried that he was engaged in state policing, and they confronted him with menace; finally he was forced to defend himself with firearms. The military engineers who descended on the Highlands after Culloden were also

personae non gratae.

In July 1747 a man called John Russell, who was charged with overseeing repairs at Inversnaid Barracks, in the stomping ground of Rob Roy

MacGregor’s clan, reported: ‘as I was sitting in my hutt at Innersnaid, two fellows who were Strangers to me came in without asking any Questions. On my Enquiring what they wanted, one of them drew a durk or rather a small Cutlass, and said he would let me know that presently.’ The engineer only escaped death by the unexpected intervention of two Highland women who ‘got between me and the Man who had the Durk, and saved me from

receiving

the Intended Blow’. Many Hanoverian officers and soldiers turned to drink while working in north and west Scotland, and the Chief Engineer there was forced to apologise to the Board of Ordnance for the ‘scandalous Scrawl and form’ of one of his underlings’ reports, commenting with wry displeasure that ‘I fancy he has consulted the Dram bottle.’ The ‘

highwaymen

’, as the military road-builders were known, were notorious drunkards. Indeed, virtually the only consolation for what Wade admitted to be ‘the remote situation’ and ‘unwholesomeness’ of their working lives was the promise of unlimited home brew. After taking pity on a small team of men with a donation of a few shillings, Samuel Johnson recounted that he came across them again further down the road. They ‘had marched at least six miles to find the first place where liquor could be bought’, he recorded.

Despite the suspicion with which map-makers and Hanoverian military men were regarded in the Highlands, William Roy often had no choice but to confront passers-by or to knock at the doors of Highland crofts. He needed to discover the names of nearby mountains, rivers or settlements for his map; Watson was also keen on encouraging his employees ‘to be particularly attentive to the produce of each part of a Country, and how Inhabited, if abounding in Grass and Hay’. All of these ‘particulars you may be easily informed’ about ‘after some Acquaintance with a Judicious Countryman’, Watson declared confidently. The first years of the Military Survey must have taken their toll on Roy and when on Christmas Day 1748 his father died, we can imagine that the prospect of returning to work in the spring to begin another season of mapping the Highlands mile by mile, alone, was daunting.

There was some compensation for Roy’s graft, however. It is easy to

romanticise

the life of the map-maker: to imagine the exhilarating panoramas, the plentiful moments of peace and the loving familiarity engendered with every fold of the landscape. But although this was not the whole truth, Roy did

rhapsodise over ‘a scene the most wild and romantic that can be imagined’ at Coigach, a peninsula in Wester Ross in the north-west Highlands. And the intense solitude and silence did not trouble him. Where David Watson

revelled

in easy anecdote among the higher reaches of Hanoverian society, Roy by his own admission did not ‘love much talking’. ‘I am for coming to the point,’ he admitted ruefully. He would later write that ‘a much truer notion may be formed’ of the nation in maps ‘than what could possibly be conveyed in many words’.

D

AVID

W

ATSON WAS

all too aware that William Roy was faced with the mammoth task of constructing a map of the Scottish Highlands on his own. Since the earliest days of the endeavour Watson had repeatedly petitioned the Board of Ordnance for assistance for his young employee, but nothing had materialised. In 1748, almost a year after the Military Survey’s

commencement

, Watson received the displeasing information that two engineers who had been expressly promised for the Military Survey were to be employed elsewhere. ‘The Surveying Scheme has given me Infinite Pain,’ he complained to the Chief of Engineers in Scotland, William Skinner. In March 1749 the Board finally relented. Almost two years into the project, George II consented to Roy ‘having three more Assistants in the Survey he is making of Scotland’. Very little documentation from the Military Survey has survived, so it is hard to pinpoint how much of the Highlands Roy had managed to cover on his own, but we can surmise from Watson’s continual appeals for assistance that his progress had been rather slow.