Make: Electronics (15 page)

Authors: Charles Platt

Figure 2-19.

Using automatic wire strippers, when you squeeze the handles the jaw on the left clamps the wire, the sharp grooves on the right bite into the insulation. Squeeze harder and the jaws pull away from each other, stripping the insulation from the wire.

Macho hardware nerds may use their teeth to strip insulation from wires. When I was younger, I used to do this. I have two slightly chipped teeth to prove it. Really, it’s better to use the right tool for the job.

Figure 2-20.

To remove insulation from the end of a thin piece of wire, you can also use wire cutters. This takes a little practice.

Figure 2-21.

Those who tend to misplace tools, and feel too impatient to search for them, may feel tempted to use their teeth to strip insulation from wire. This may not be such a good idea.

Connection Problems

Depending on the size of toggle switches that you are using, you may have trouble fitting in all the alligator clips to hold the wires together. Miniature toggle switches, which are more common than the full-sized ones these days, can be especially troublesome (see Figure 2-22). Be patient: fairly soon we’ll be using a breadboard, which will eliminate alligator clips almost completely.

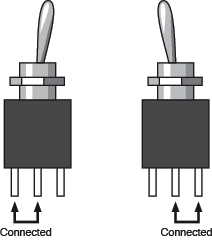

Figure 2-22.

Miniature toggle switches can be used—ideally, with miniature alligator clips—but watch out for short circuits.

Testing

Make sure that you connect the LED with its long wire toward the positive source of power (the resistor, in this case). Now flip either of the toggle switches. If the LED was on, it will go off, and if it was off, it will go on. Flip the other toggle switch, and it will have the same effect. If the LED does not go on at all, you’ve probably connected it the wrong way around. Another possibility is that two of your alligator clips may have shorted out the battery.

Assuming your two switches do work as I described them, what’s going on here? It’s time to nail down some basic facts.

Fundamentals

All about switches

When you flip the type of toggle switch that you used in

Experiment 6

, it connects the center terminal with one of the outer terminals. Flip the switch back, and it connects the center terminal with the other outer terminal, as shown in Figure 2-23.

Figure 2-23.

The center terminal is the pole of the switch. When you flip the toggle, the pole changes its connection.

The center terminal is called the pole of the switch. Because you can flip, or throw, this switch to make two possible connections, it is called a

double-throw switch

. As mentioned earlier, a single-pole, double-throw switch is abbreviated

SPDT

.

Some switches are on/off, meaning that if you throw them in one direction they make a contact, but in the other direction, they make no contact at all. Most of the light switches in your house are like this. They are known as

single-throw switches

. A single-pole, single-throw switch is abbreviated

SPST

.

Some switches have two entirely separate poles, so you can make two separate connections simultaneously when you flip the switch. These are called

double-pole switches

. Check the photographs in Figures 2-24 through 2-26 of old-fashioned “knife” switches (which are still used to teach electronics to kids in school) and you’ll see the simplest representation of single and double poles, and single and double throws. Various toggle switches that have contacts sealed inside them are shown in Figure 2-27.

Figure 2-24.

This primitive-looking single-pole, double-throw switch does exactly the same thing as the toggle switches in Figures 2-23 and 2-27.

Figure 2-25.

A single-pole, single-throw switch makes only one connection with one pole. Its two states are simply open and closed, on and off.

Figure 2-26.

A double-pole, single-throw switch makes two separate on/off

connections.

Fundamentals

All about switches (continued)

Figure 2-27.

These are all toggle switches. Generally, the larger the switch, the more current it can handle.

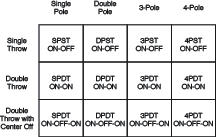

To make things more interesting, you can also buy switches that have three or four poles. (Some rotary switches have even more, but we won't be using them.) Also, some double-throw switches have an additional “center off” position.

Putting all this together, I made a table of possible types of switches (Figure 2-28). When you’re reading a parts catalog, you can check this table to remind yourself what the abbreviations mean.

Figure 2-28.

This table summarizes all the various options for toggle switches and pushbuttons.

Now, what about pushbuttons? When you press a door bell, you’re making an electrical contact, so this is a type of switch—and indeed the correct term for it is a momentary switch, because it makes only a momentary contact. Any spring-loaded switch or button that wants to jump back to its original position is known as a momentary switch. We indicate this by putting its momentary state in parentheses. Here are some examples:

- OFF-(ON): Because the ON state is in parentheses, it’s the momentary state. Therefore, this is a single-pole switch that makes contact only when you push it, and flips back to make no contact when you let it go. It is also known as a “normally open” momentary switch, abbreviated “NO.”

- ON-(OFF): The opposite kind of momentary single-pole switch. It’s normally ON, but when you push it, you break the connection. So, the OFF state is momentary. It is known as a “normally closed” momentary switch, abbreviated “NC.”

- (ON)-OFF-(ON): This switch has a center-off position. When you push it either way, it makes a momentary contact, and returns to the center when you let it go.

Other variations are possible, such as ON-OFF-(ON) or ON-(ON). As long as you remember that parentheses indicate the momentary state, you should be able to figure out what these switches are.

Figure 2-29.

This evil mad scientist is ready to apply power to his experiment. For this purpose, he is using a single-pole, double-throw knife switch, conveniently mounted on the wall of his basement laboratory.