Kate Berridge (19 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Even as the executioner staged an instant auction for the King's hat, and did a brisk trade in locks of hair and buttons, the mortal remains were taken with the utmost security to the Madeleine cemetery, the King's head placed between his legs in a wicker basket on a cart that

was escorted by an armed guard. As the official reports emphasized, the body was transported with the utmost âcare and exactitude'. Nothing about the disposal of the body was left to chance. The Commune, which masterminded every detail, even planned the site of the grave as a propaganda exercise. The King was to be interred between the victims who had died on his wedding day, when celebration had turned to tragedy and they had been crushed to death, and the bodies of the Swiss Guard massacred by the people on 10 August. The extra-deep grave was filled with double layers of quicklime. While the scaffold sale of a few material relics was indulged as the executioner's traditional perk, the royal remains were another matter. As Mercier later wrote, the double dose of quicklime was to ensure that âit would be impossible for all the gold of the potentates of Europe to make the smallest relic of his remains.'

The quest to obliterate any material that could inflame sentiments of martyrdom went further. Keen to avoid anything that might confer on the dead King a posthumous power that would further the counter-revolutionary cause, the General Council ordered the ritual burning of all remaining personal effects at the Temple. The official document decreed, âThe bed, the clothes and everything that served for the housing and clothing of Capet will be burned in the Place de Grève.' Erasing the memory of monarchy was also the motive behind the orders for the ritual desecration of all the royal tombs at Saint-Denis in August, an official orgy of vandalism against royal bones and headstones.

The high-security operation on 21 January evidently did not prevent Marie with her carpet bag of tools rushing to the Madeleine cemetery, where she modelled the royal head before it was consigned to the quicklime. Or so the story goes, backed up by the death headâthe ultimate revolutionary relicâwhich is still on display in the Chamber of Horrors, and which old catalogues describe as âTaken immediately after his execution by the order of National Assembly of France, by Madame Tussaud's own hands'. Successive generations of the Tussaud family have insisted on its authenticity: for example, John Theodore Tussaud, Marie's great-grandson, writes in his memoirs, published in 1919, âThe casts were undoubtedly taken under compulsion, with the object of pandering to the temper of the

people, or of serving as confirmatory evidence of execution having taken placeâperhaps both.'

Quite why the authorities should have made an exception to their campaign of erasing the memory of the monarchy by conserving such a potent reminder is unclear. The death head is never mentioned in other sources, and how likely is it that the authorities would allow someone who (by her own account anyway) had been a member of the royal household to record and potentially replicate the King's image, so as to make him âspecial' again? Given that statues of the King were being pulled down by official orders, which is well documented, the modelling of the head seems even less likely. In fact from 1793 until the end of Marie's life, in 1850, there is no record of this relic ever having been displayed. There is also documentary evidence to support the theory that the royal execution was never the subject of a tableau in the original exhibition in Paris. A journalist, Prudhomme, publicly criticized Curtius for not commemorating the execution of the King in his exhibition, but showing instead a tableau of the assassination of the Jacobin deputy Lepeletier, whom a royalist had murdered in revenge for his part in voting for the King's death, on the evening before the King was guillotined.

As the Revolution escalated, Curtius and Marie were ultra-cautious about their royal models, so much so that pretty early on they had diplomatically removed the King and Queen from their places at the Grand Couvert. The first appearance of the King's head was in the Baker Street exhibition in 1865, fifteen years after Marie's death. It is as if, using the past as a resource from which to make new attractions, her heirs constructed from a mould of the living King a mock-up of him in death, creating a convincing decapitated head, and a sensational relic of a regicide. This helped to propagate the by now already well-established myth of Marie as the reluctant recorder of history. As one catalogue put it, âThus it was that she was compelled again to work with tear-dimmed eyes and take impressions of the dead features of many who had been her friends in happy Versailles days.' Another was even more melodramatic: âSo again was her art to write history, but to write it in letters of blood!'

In the febrile climate following the execution of Louis XVI, exhibiting an effigy of the King could easily be misconstrued as an

expression of royalist sympathy. Curtius had already had a brush with bad press after Lafayette, formerly the darling of the Third Estate, fled the country as public enemy number one. Yet his figure stayed behind on show, and outstayed its welcome in the eyes of the public. With his charismatic approach to crisis management, Curtius had rectified the situation with a spectacular decapitation of the figure of Lafayette in the street outside the exhibition. But in 1793, with Robespierre the new star in the republican firmament and England and Spain having joined the revolutionary war, the authorities were less forgiving. Now a similar wrong move could result in prison and a death sentence. This was a period of paranoia and surveillance, of informing and spying, of bribery and betrayal. The raised stakes became all too apparent when a German showman, Paul de Philipstal, misjudged his material. Since his arrival in Paris in the winter he had been wowing audiences at the Hôtel de Chartres with his twice-nightly Gothic variety show. Styled as a phantasmagoria, it was a technically brilliant magic-lantern show with a supernatural theme. In a blacked-out chamber with an eerie Halloween-style set with skeletons and tombs, the audience jumped out of their skin when lightning flashes announced the arrival of the undead. In a now-you-see-them-now-you-don't fright-fest of reappearing and disappearing, the audience were seriously spooked.

One of his crowd-pleasing flourishes by way of a grand finale was a risqué satirical allusion to a recognizable public figure. A journalist writing about the show in March 1794 described how variously the faces of Marat and Robespierre were superimposed on to a slide of a cloven-hoofed devil. It is extraordinary that Philipstal got away with such audacious stunts for so long. But his luck ran out when a wrong slide change meant that an image of Louis XVI was shown such that the King seemed to be flying upwards as if ascending to heaven. The audience overreacted, interpreting this as a subversive display of respect for the late King, and Philipstal was duly arrested and incarcerated. It was Citizen Curtius to whom his distraught wife appealed for help. There is something almost Masonic about the kinship of showmen, but Curtius was probably motivated by more than charitable instinct when he agreed to help such a wealthy and successful name on the international circuit, and a respected innovator. It is evidence of Curtius's propensity for having the right friends in the right

position of power at the right time that he knew Robespierre well enough to call upon him to intervene. In the version of this transaction that appears in Marie's memoirs, the reputation of Robespierre as incorruptible is called into doubt. Marie implies that he was not immune to bribery. As her memoirs relate, âOn M. Curtius leaving the room after having obtained an order for setting Philipstal at liberty, he left on the table three hundred Louis, without saying a word to Robespierre about them; as they were never sent back there can be no doubt that the gift was accepted.' The fact that Philipstal was indebted to Curtius would alter the course of Marie's life when he reappeared at a later date, offering what she thought was an opportunity for the favour to be returned.

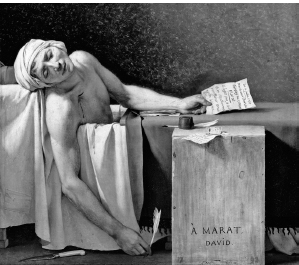

An iconic image of the Terror is the death of Maratâmeeting his ultimate deadline like a true journalist, still clasping his pen in his hand. His final moments after his assassination by Charlotte Corday are immortalized both in the famous painting by David and in the wax tableau attributed to Marie. David's painting is both monumental and poignantly mundaneâthe vinegar-soaked turban is a reminder of Marat's skin disorder, the bath prosaic when compared to an elegant deathbed or a heroic battlefield. Yet the ignominious circumstances were no bar to the cult of Marat that followed his death, and which the waxwork tableau did much to propagate. Successive catalogues from the time Marie came to England list Marat's image as âtaken immediately from life by order of the National Assembly', and often this particular exhibit was singled out for attention in the press. In the touring years, for example, the

Derby Mercury

of 1 December 1819 referred to âthe very finely modelled figure of the noted French Revolutionary Character Marat' and went on: âthis subject is considered the chef d'Åuvre of the ingenious artiste.' On 11 October 1828 the

Lancaster Gazette

invited its readers to âShudder at the objects in the Second Room. Behold the bloody revolutionist in the agonies of death.' Marat's death throes evidently didn't move everyone: for Charles Dickens, the most horrific sight in the Chamber of Horrors was a man looking at Marat âwhile eating an underdone pork pie'.

The two works, in wax and in oil, are perhaps linked by more than common subject matter. In the heat of a summer night, 13 July 1793

at 7.45, a doctor certified the death of Marat only hours after his assassination by Charlotte Corday. In sympathy with the Girondins, who had fallen from power, she had talked her way into Marat's room and plunged a knife into his chest. The hot weather and the rawness of his skin disorder accelerated the rate of decomposition. This posed an immediate problem for the official-martyrdom theatricals that were an important aspect of Revolutionary propaganda. The body of the assassinated deputy Lepeletier had been displayed in a dramatic nude parade, but that had been in the cold January weather. For four days his naked body, styled in a classical pose, was exposed to the elements on a pedestal that mourners ascended via a staircase. With Marat, the hot weather and state of the corpse meant speed was of the essence, and a fast funeral was in order. Even the embalming went wrong, and the clichéd excuse âIt just came off in my hand' was the macabre truth as an expert team of embalmers tried to put Marat together again, like Humpty-Dumpty. On 14 July the botched and blotched cadaver was arranged with great care on a dais in the Cordeliers Club, and with plenty of artificial lighting, and round-the-clock incense, it passed muster for public view. Also on display were the bath in which he had died and the packing-case writing desk. For two days only, by which time not even copious air freshening could mask the smell, mourners paid their respects. The funeral, brought forward to 16 July, included all David's signature touches: cardboard trees, silver-foil lyres, and young girls in white. Louis Sade (formerly known as the Marquis de Sade) gave the funeral oration.

David's original hope had been to display the body just as he himself had last seen Marat, when he visited him on the evening before he was assassinated and found him working in the bath. As he told the Convention, âI thought it would be interesting to show him in the attitude in which I found him, writing for the happiness of the people.' As the state of the corpse prevented the accurate reconstruction of this scene, necessitating less exposure of the body, David determined to represent it in the commemorative oil painting he had been commissioned by the National Convention to paint. It took four months for David to complete

Marat Assassiné

, which was presented to the Convention on 14 October 1793.

The death of Marat. Was the wax model a source for David's painting, or the other way round?

The delay between the death and the completion of the painting, and also the composition of the painting, are a cue for Marie to enter the scene. For she always claimed that a commemorative wax tableau was the visual reference for David's work. As her memoir states, âIt was by his orders that Madame Tussaud took a cast from the face of Marat, as also of Charlotte Corday, after death, from which David made a splendid picture of the scene of the monster's assassination, and had written upon it, “David à Marat”, for whom he pretended an extraordinary friendship.' She described being fetched by âsome gens d'armes', who took her to Marat's house expressly to take a cast from the dead man's face. âHe was still warm, and his bleeding body and the cadaverous aspect of his almost diabolical features presented a picture replete with horror, and Madame Tussaud performed the task under the influence of the most painful emotions.' But did she go to the actual scene of the crime? It seems more likely that the public lying-in-state for two days was her chance to observe and replicate the necessary elements for her tableau version of Marat's martyrdom. In pride of place at the Boulevard du Temple exhibition, it was a star attraction in the months after his death, when the cult peaked. (One facet of this hero worship was a boom of baby boys named Marat.) Marie relates how this new exhibit became a focus of public outpourings of grief, with the crowds âloud in their lamentations'. She goes on to describe how a further publicity coup happened when Robespierre recommended the new exhibit. As he left, he invited passers-by to follow his example and âsee the image of our departed friend, snatched from us by an assassin's hand', and to weep with him for the bitter loss. Robespierre's approbation was evidently highly effective: as the memoirs testify, the tableau was so popular that âpeople poured in to the exhibition to see the likeness of their idolised Marat, and for many successive weeks, twenty-five pounds a day was taken.'