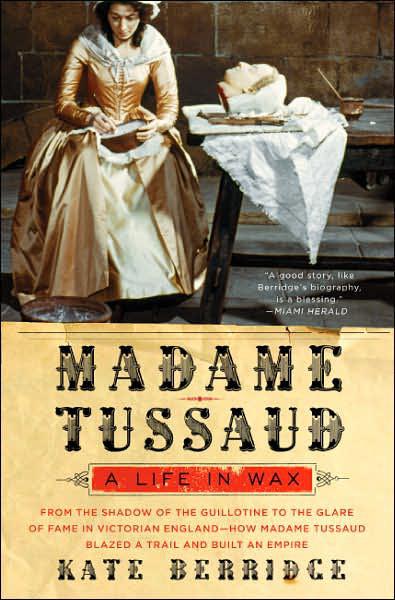

Kate Berridge

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

A Life in Wax

For Sebastian

We cannot imagine how difficult it must have been for her to make casts from the faces of her dead friends. But she had no choice. She was more or less told, âDo it, or you'll be the next one to have your head cut off?'

Anthony Tussaud, great-great-great-grandson, 2002

Â

1.

The Curious Cast of Marie's Early Life

2.

Freaks, Fakes and Frog-Eaters: An Education in Entertainment

3.

The King and I: Modeller and Mentor at Versailles

4.

Courting the Crowds at the People's Palace

5.

Marie and the Mob

6.

Model Citizens

7.

The Shadow of the Guillotine

8.

Hardship and Heartache

9.

Love and Money

10.

Vide et Crede! The Lyceum Theatre, London

11.

Scotland and Ireland 1803â1808

12.

âMuch Genteel Company'

13.

Dramas and Dangers 1822â1831

14.

âAn Inventive Genius': Mrs Jarley, Madame Tussaud and Charles Dickens

15.

âThe Leading Exhibition in the Metropolis'

16.

Bringing the Gods Down to Earth

Â

Epilogue

Â

2. âChange the Heads!', cartoon by P. D. Viviez, 1787

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

4. Paul Butterbrodt, giant at the Palais-Royal

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

5. Benjamin Franklin, attributed to Madame Tussaud

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

6. Marie Grosholtzâa rare early portrait, anonymous

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

7. Le Grand Couvert, Salon de Cire, Palais-Royal

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

8. Interior with people, Salon de Cire, Palais-Royal

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

9. Gouache by Etienne Le Sueur

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

11. Philippe Curtius, engraving by Gilles Louis Chrétien

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

13. A Bastille valance

(copper-plate-printed cotton; V & A images / Victoria & Albert Museum)

14. The Comte de Lorges, by Madame Tussaud

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

16. Guillotine blade bought from the Sanson family

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

18. The death of Marat, wax tableau

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

21. Mrs Salmon's Waxworks

(Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

22. Letter with envelope, 25 April 1803

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

23. Wombwell's Menagerie, drawing by George Scharf

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

24. Freakshow caravan, drawing by George Scharf

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

25. âThe Working Class' notice, Portsmouth, 1830

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

26. Signor Bertolotto's Industrious Fleas

(Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

27. The Gigantic Whale

(Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

28. âMonster Alligator' caravan, drawing by George Scharf

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

29. The Bristol Riots, 1831, watercolour by William Muller

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

30. Madame Tussaud with spectacles, 1838

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

33. Interior of the Bazaar, Baker Street, with orchestra

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

34. Madame Tussaud, by Paul Fischer, 1845

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

35. Marie Tussaud, by Francis Tussaud

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

36. Richardson's Rock Band

(Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

37. Family-group in silhouette by Joseph Tussaud

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

38. Omnibus with advertising

(anonymous)

39. An Old Bill Station

(with thanks to The London Library)

40. âThe Ambulatory Advertiser', drawing by George Scharf

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

41. Poster advertisement for Madame Tussaud and Sons, showing Napoleon's carriage, 1846

43. Madame Tussaud's death mask, by Joseph and Francis Tussaud

(Madame Tussauds Archives, London)

T

HIS IS A

story about a queue which started in Paris in around 1770 and which still snakes around cities all over the worldâLondon, New York, Las Vegas, Amsterdam and Hong Kong. In London, the perpetual queue is a familiar landmark, and taking up a place in it is a rite of passage, with those who went as children returning as parents. Undeterred by long delays and London rain, people of all ages and nationalities wait patiently for their turn to pass through the doors of a vast, windowless building, purpose-built in 1884 to accommodate their rising numbers. The building has the architecture of secrecy about it, and there are no clues as to what lies inside, but if you raise your eyes above the height of the passing double-decker buses you will see a silhouette portrait of the woman whose name the building bears, with the dates of her life: Madame Tussaud 1761â1850.

Madame Tussaud has generally been neglected as a quaint irrelevance to mainstream history. Rather too readily dismissed as a pretentious show-woman, she has received barely a mention in the footnotes of historical record. Marginalized by the Establishment, she has been seen as only slightly more credible than a fairground entertainerânot authoritative enough to be taken seriously as either an artist or an historian. To a degree, she has suffered from the prejudice that still treats popular culture as an embarrassing nouveau-riche relation to art and culture proper. The celebrity-filled waxworks presented under her name are all too readily written off as a flashy, frivolous entertainment. This is to underestimate their original function in a period with a limited pictorial reference, when they supplied a visual narrative of events.

When the notion of a personal copy of a newspaper was still a long way in the future, her wax artefacts supplied a commodity which in

Georgian England was in short supply: information, the most basic unit of which was news. As visual dispatches, her figures were an accessible format of both foreign and home news. When most illustration was monochrome, and primitive woodblocks provided only poor-quality likenesses, her life-size colourful mannequins of murderers and monarchs were a source of wonder and delight.

Nowadays, when every picture sells a story, one could say Madame Tussaud was the original tabloid journalist, her topical tableaux supplying the mass market with a constant stream of the sensational and newsworthy. Reporting royal news was a particular strength, and coronations became her stock-in-trade. These were not confined to legitimate claimants to crownsâa story that in her hands ran and ran was the rise and fall of Napoleon, an epic narrative of self-made success for which her status-conscious audience never lost their appetite.

As well as reporting the present, Madame Tussaud represented the past. She prided herself on the pedagogical function of her exhibition, and applied her ethos of learning and leisure to historical biography. Her interpretation of history in human terms, rather than as an impersonal series of laws and wars, struck a chord with an audience for which the lives of great men of the pastâbesides patriotic prideâwere starting to kindle fantasies of their own aspirations. This version of the past was subjective, but always determined by public interest.

Most of the few museums and national art galleries that existed in the first half of the nineteenth century seemed to do everything in their power to keep the public out, whereas Madame Tussaud strived for accessibility. Long before governments deemed public museums and libraries a worthwhile addition to the civic welfare agenda, Madame Tussaud blazed an impressive trail of private enterprise in the service of public interest. It was only after her death that the profits from the Great Exhibition were deployed to fund the three core repositories of public learning, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Natural History Museum and the Science Museum.

The backdrop to Madame Tussaud's life story is fear of the crowd. This engendered a form of cultural apartheid whereby the pleasures and cultural diet of different classes were strictly regulated. In her lifetime she witnessed the most destructive capability of people en masse, which continued to haunt the Establishment. But in tandem

with this was a more positive aspect of people powerâas mass-market consumers curious to know about the human face of both history and the here and now. Madame Tussaud recognized this and, tailoring her entertainment for the burgeoning middle classes in particular, she set in motion the mechanics of her own success, melting existing hierarchical barriers in the process. By catering to the crowd as consumers, not patronizing them as philistines or fearing them as a serious threat to public order, she took a radically different stance from the custodians of culture in Georgian and early Victorian England. Instead of fearing the barbarians at the gate, she charged them admission and sold them catalogues. Significant aspects of her achievement were her exploitation of public interest and her recognition of the binding power of popular culture. As Joseph Mead wrote in 1841, âMadame Tussaud has built her fortune on common sympathiesâthousands crowd her rooms: princes, merchants, priests, scholars, peasants, schoolboys, babies in one common medley.' Recognizing the rich pickings to be made from popular interest in the famous and infamous, she harnessed her considerable entrepreneurial energy to cater to it, outclassing all the rivals for the same market.

An article in

Chambers's Journal

at the turn of the century considers both the perennial appeal of the waxworks and the phenomenon of their fame:

The taste for waxworks is universal, and one upon which we might moralise at great length. It is part and parcel of that taste for dolls, which most girls manifest, and which clings to the very many even when they have ceased to be children. Viewed in this light Madame Tussaud's exhibition is a huge glorified dolls' house with a strong human element attached. But it is more than this. It is a kind of national monument and the name of its foundress is more familiar too, and probably more thought about by thousands of English men and women, than is the name of the genius who built St Paul's.

In terms of brand recognition, Madame Tussaud's is one of the most successful names in the commercial world. It has a familiarity which even in her lifetime extended abroad and, more pertinently, across classes. Long before Mr Henry Harrod went to the rescue of one of his trade customers, a grocer in Knightsbridge, and overhauled his

ailing business so that it became one of the most famous shops in the world, and before Monsieur Schweppes got the lucrative contract for distributing non-alcoholic âeffervescent beverages' to refresh the visitors at the Great Exhibition, Madame Tussaud imprinted her name in the minds of an impressive number of the population of England, Scotland and Ireland, and became a byword for commercial success. In establishing herself as a brand, she recognized the role of advertising, and at a time when this industry was in its infancy she proved herself a pioneer in exploiting and innovating various forms of publicity.

In the wake of her own extraordinary rise to fame and fortune, which peaked in the final decade of her life, her unique hall of fame came to exert a great influence, and she herself was regarded as an unofficial arbitrator of worldly success. In 1849

Punch

magazine referred to âThe Tussaud Test of Popularity':

In these days no one can be considered properly popular unless he is admitted into the company of Madame Tussaud's celebrities in Baker Street. The only way in which a powerful and lasting impression can be made on the public mind is through the medium of wax. You must be a doll at Madame Tussaud's before you can become an i-dol(l) of the multitude. Madame Tussaud has become in fact the only dispenser of permanent reputation.

Inclusion in her exhibition was the definitive proof that one had attained celebrity status. Conversely, exclusion pricked the pride of the most unlikely people: the great historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, on hearing of the death of Madame Tussaud, confided in a letter to a friend, âI can wish for nothing more on earth, now that Madame Tussaud in whose Pantheon I hoped once for a place is dead.' The exhibition was both denigrated as an insignificant amusement arcade and venerated as a secular cathedral.

As a prism through which to see the present afresh, the story of Madame Tussaud provides an unparalleled perspective on the emergence of the cult of celebrity. Her long life saw a general cultural shift in interest away from posthumous glory in heaven to a greater preoccupation with self-definition on earth. For a society increasingly transfixed by the lure of earthly fame, Philippe Curtius, her

predecessor, mentor, and founder of the original waxworks exhibition in Paris, and Madame Tussaud after him, promoted a compelling form of secular idolatry. They pandered to a growing cult of admiration, in which a new regard for the standing of others in the public arena was a by-product of an increasingly status-conscious society. In times effervescent with change, and a period of history in which democratic currents were destabilizing the status quo, the waxworks exemplified an emerging culture of impermanence. They highlighted the mutability of fame, and the shadow side of human nature that is reflected in our propensity to topple those whom we have placed on pedestals. From its earliest origins in pre-Revolutionary Paris, the exhibition showed how the ascent of human ambition celebrated in wax can be followed by meltdown, just as Icarus âfelt the hot wax run, unfeathering him': those no longer of public interest are ignominiously removed. The waxworks were and are a brutal index of our voyeuristic fascination with the fall as well as the rise of celebrities, and of the waning of our loyalties that make us fickle fans.

Underpinning the rise of Madame Tussaud's exhibition is a remarkable personal story of survival, weathering reversals of fortune, and life-threatening incidents that would have defeated a lesser being. Success was a triumph over cultural, commercial and personal setbacks. And what of the woman herself? One of the most famous names in the world belongs to a woman whom many people in the queue think is a fictional character. Long-standing myths and anecdotes repeated so often they have assumed the credibility of facts have fuelled a sense of someone larger than life, but whose life is never really fleshed out. It is a central proposition of this book that many of these myths were given birth by her, as she created her own image as deftly as one of her models.

The public persona she assumed when she came to England was an integral part of her branding. Having presented herself as a victim and survivor of the French Revolution, Madame Tussaud remains for all time suspended in people's imagination as a young woman with a guillotine-fresh head in her lap. The image of an innocent woman in a bloody apron being forced to make death heads to save her own neck elicited both sympathy and curiosity in her public. The power of this image was increased by her claims to have known many of the people

whose heads she was forced to mould. She made much of her early life as a pet of the palace of Versailles, where in the final days of the

Ancien Régime

she was art tutor to Madame Elizabeth, sister of Louis XVI.

The most effective way in which her early history fed the myth was via the official memoir published when she was in her late seventies as

Madame Tussaud's Memoirs and Reminiscences of France, Forming an Abridged History of the French Revolution

. This is the principal source of information about Madame Tussaud for the first half of her life, until she came to England. Written in the third person by a family friend and émigré, Francis Hervé, as if dictated to him, the book seems curious in style to present-day readers. It is telling that Hervé even puts in a disclaimer, attributing any inaccuracies to Madame Tussaud's great age: âFor although the memory of Madame Tussaud is remarkably clear for events, it is not the same for dates, being nearly eighty years of age and having passed so considerable a period of her life in a state of excitement, the recollections must sometimes be in a degree confused and impaired.' After this apologia, in a rather opportunist way, he recommends the more reliable work on the Revolution that his brother has written. More recent biographers have not been so cautious, and have tended to disregard or downplay the lacunae in Madame Tussaud's own version of her early life, and so the myths have endured.

Unpicking the embroidery of her early life in France from the flimsy framework of fact is complicated by scant sources. Until the middle-aged Madame Tussaud steps off the packet ship in England and into her identity as victim and survivor of the Revolution, the only previous references to her are in a handful of legal documents.

In three distinct phases of her life she is concealed by different means. For the first half of her life in France, her unreliable memoirs conceal far more than they reveal. She is least clearly seen in her apprenticeship years, learning her craft. In contrast to her charismatic mentor Curtius, whose presence in public records confirms his pre-eminence in the Paris entertainment scene, we can only imagine his talented charge, a slight-framed girl, anonymous in the pullulating crowds of the entertainment district where the original exhibition had a site. Her omissions are glaring. There is nothing about personal relationships with her mother and Curtius, just a smokescreen of anecdote and half

truths, giving the overall impression of a real person being obscured by an illusory identity.

Later, in England, it is not just psychological but also physical absence that is the challenge. From 1802 for almost twenty-seven years Madame Tussaud was on the road, among the travelling showmen whose tracks are so faint in historical records. To track this phase of her progress we have only a paper trail of entertainment ephemera (precious remnants of her publicity material) and a few letters home, which stop abruptly in 1804.

In the final phase of her life, at the height of her fame, the identification of her with her exhibition is complete. Now she is hidden behind the institution, and eclipsed by the brand she has built. Although her creation had almost a permanent presence in the press, and she was regularly sighted at the exhibition until almost the very end of her life, the woman who enabled a paying public to get close to the famous remained ironically elusive. Like a waxwork, she seems more lifelike than alive. We have few insights into either her feelings or her opinions and those things that convey the texture of personality.