Kate Berridge (17 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

She had ample opportunity to formulate her impressions of Marat, because on one of the many occasions when his newspaper

L'Ami du peuple

incurred the enmity of the authorities he sought asylum at her home. She relates how he arrived with a carpet bag and stayed for a week. He appears to have been an undemanding house guest, spending most of the time writingââalmost the whole day in a corner with a small lamp'. On one occasion he subjected her to a private hearing of his political rhetoric, tapping her on the shoulder âwith such roughness as caused her to shudder, saying, “There, Mademoiselle, it is not for ourselves that I and my fellow labourers are working, but it is for you, and your children, and your children's children. As to ourselves we shall in all probability not live to see the fruits of our exertions”; adding that “all the aristocrats must be killed.” ' She then describes a chilling postscript to her conversation with him when Marat âmade a calculation of how many people could be killed in one day, and decided that the number might amount to 260,000 [

sic

]'. She described his newspaper as âone of the most furious, abusive and calumnious productions which ever appeared, its object being to inflame the

minds of the people against the King and his family, and in fact to incite them to revolt and to the destruction of every institution and individual likely to afford support to the tottering monarchy'.

The silence of what Marie omits from these recollections of her fanatical guests, namely the personal feelings they evoked in her, is deafening. Given her supposed eight-year tenure as royal art tutor at the palace of Versailles, and the strong bonds of reciprocal friendship she professed between herself and Madame Elizabeth, she seems to have shown great restraint in withholding any royalist sympathy in the face of Marat's republican rants. Interpretation of her reticence depends on how much credence one gives to the story of her life presented in the memoirs. In the eye of the Revolutionary storm her fence-sitting is the sign not of an unfeeling person, but of a prudent person; restraint at that time would have been understandable. But far away from the dangerous atmosphere of Revolutionary Paris, when recollecting events so many years later, her reticence is baffling. Rather as moths adapt their wing colour as a survival camouflage, perhaps Marie's apparent thick skin was developed as a survival mechanism in dangerous times. Decisions about the content of the exhibition were becoming fraught. Curtius's aristocratic connections were what propelled him into the Parisian limelight in the first place, and Marie made much of her links to the court circle. One surmises that she would have been torn between preserving the

haut ton

of the exhibitions with royals and courtiers, and focusing more on the new wave of activists and agitators. If Curtius was more naturally disposed to the latter course, and jumped on every passing bandwagon, then Marie's strategy was to cultivate the impression of being an innocent victim of circumstances, a reluctant collaborator. (In England she always defended Curtius's reputation, and claimed he too had been a royalist compromised by circumstances. The

London Saturday Journal

in 1839 reiterated the claims in the memoirs: âHer uncle always persisted in saying, however, even after he had fairly joined the revolutionists, that he was a royalist at heart, and that he had only favoured these visionaries, and entered into their views, to save his family from ruin.')

An important element in the realignment of social values and the secularization of France at this time was the energy that went into demoting the power of tradition by devising new rituals. David

played a major role in masterminding the aesthetic of the Revolution, and according to Marie he was an associate of Curtius and a familiar face at the family home. In what appears as a consistent theme of her own magnetic attraction for powerful menâremember the King's brother tried to kiss her, Voltaire complimented her on her looks, Robespierre called her a pretty patriotâDavid was always very good-natured towards her, but his originality clearly deserted him in using the old cliché of âalways pressing her to come and see his paintings'. It was an unreciprocated admiration: she calls him a monster, and âmost repulsive'. âHe had a large wen on one side of his face, which contributed to render his mouth crooked; his manners were quite of the rough republican description, certainly rather disagreeable than otherwise.' David was evidently acutely self-conscious about âthe revolting nature of his countenance, manifesting the utmost unwillingness to have his likeness taken.' However, Marie evidently persuaded him and although the likeness did not come with her to England, she states that she produced âa most accurate resemblance of that eminent artist'.

Whatever Marie's personal relationship with David, he incorporated a wax figure of Voltaire in the festival dedicated to the writer in July 1791. This was the second time that wax figures from the exhibition had played an integral role on the wider stage of the Revolution, but the earlier impromptu use of two busts in July 1789 was very different from the carefully choreographed role that the figure of Voltaire played on this occasionâaboard a magnificent chariot and clad in vermilion robes. It was the centrepiece of a cast-of-thousands production devised by David for the writer's grand entry into the Panthéon. In his diary, Lord Palmerston referred to âa figure of Voltaire very like him in a gown' and âa very fine triumphal car drawn by twelve beautiful grey horses, four abreast'. Unfortunately, torrential rain made the colours of the robes bleed, but it was Curtius who had a red face when VIPs roundly blamed him for failing to do justice to the event with the rain-streaked figure. The press, however, were more interested in contrasting Voltaire's glory with the mocking of the King. Engravers had a field day juxtaposing Voltaire being crowned and fêted with adulatory fanfares with the King being insulted by fanfares of farts from the behinds of angels.

Only days after the Panthéonization of Voltaire, a republican rally in the Champ de Mars was quashed by force when Lafayette fired on the crowd. But the zeal of the republican cause was by now bullet-proof, and the dethronement of the King was now not likely but inevitable. Shortly after this, a brave public-relations exercise on the part of the royal family backfired horribly when the Queen, her children and Madame Elizabeth went to the Comédie-Italienne. Incensed by the leading lady, Madame Dugazon, seeming to address one aria directly to the Queen, when she sang the line âAh, how I love my mistress!', the Jacobins in the stalls could not contain themselves. Grace Elliott relates how âsome Jacobins who had come into the playhouse leapt upon the stage, and if the actors had not hid Madame Dugazon, they would have murdered her. They hurried the poor Queen and her family out of the house, and it was all the Guards could do to get them safe into their carriages.' This was the last public appearance of the Queen before that engagement that she did not plan and where she would find herself centre stage, drawing the gaze of a vast audience as drums rolled.

From the invasion of a stage and upstaging of a public performance by a few angry Jacobins, in 1792 the boundaries that were breached became more serious. The lines crossed were to involve nations and frontiers, and most dramatically the invasion of the royal family's private quarters in the Tuileries with devastating consequences. On 20 April 1792, when France declared war on Prussia and Austria, there was a sense that what had started as a popular uprising, which it was thought could be contained and directed by new authorities, was becoming increasingly unmanageable. Marie, by now a woman of thirty-one, began to live at the centre of a city where the difficulties of day-to-day life were exacerbated by war. âLa patrie en danger' heightened nationalistic fervour. Whereas the outbreak of the Revolution had provided commercial opportunities for those in show business and consumer goods, now it was the turn of others to profit from the opportunities that came with military action. Seamstresses turned their talents to uniforms, and factories and foundries went into overdrive to supply equipment and arms. Church bells were melted down for cannon. Tanneries could barely keep up with the demand for harnesses.

As hostilities escalated, ordinary civilians became embroiled in the war effort. The wives of Paris were called upon to tear up their trousseaus for bandages. (Total mobilizationâ

levée en masse

âwas officially declared by the Convention in August 1793, after a series of setbacks during the first half of that year.) Marie relates how, in response to a chronic shortage of gunpowder, âFor the purpose of obtaining the quantity of saltpetre [a prime ingredient of explosives] that was required, they were obliged to resort to the most singular measures. It was imagined that it might be procured in considerable quantity from the mouldy substance commonly found on the walls of cellars. Every private house, therefore, underwent an examination to see what might be extracted from their subterranean premises.' The austerity and enterprise of her later years probably originate from her experiences at this time. Like many civilian survivors of wars she had those distinctive badges of fortitude. A persistent shortage of animal tallow in the later years of the war was particularly difficult for the exhibition, as candlelight was crucial to the overall illusory magic of the display of figures.

But it was not just candles that were in short supply. For those in the entertainment business the sheer numbers of the men recruited as soldiers meant a drastic depletion of both customers and performers. Marie reported the enthusiasm with which people joined up, and how the quarter in which she lived âappeared almost cleared of men'. As Curtius became ever more involved in Jacobin affairs, as well as being involved in the National Guard, and as he stepped up his pursuit of his inheritance claim in Mayence in conditions more difficult by the day, Marie had to keep the exhibition afloat. Later on in England she recalled that, for the first time, in the summer of 1792 it was necessary to reduce admission charges to attract more customers. This year also saw grocery riots when, as well as bread, other foods including coffee and sugar were in short supply.

Marie was living in a city that was like an ideological building site, with drastic demolitions and radical conversions such as churches being declared Temples of Reason. In the course of the next two years, language and traditional systems for measuring time were all revised. New language was supposed to render old concepts obsolete. The King was demoted to Louis Capet, and the Duc d'Orléans

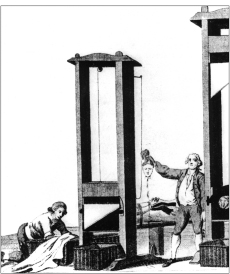

became Philippe Egalité. Many public establishments pasted up posters proclaiming âThe only title recognized here is that of citizen,' but an anecdote from the theatre shows how hard it was to implement these changes. A prima donna at the Comédie-Française called for her lackeys, only to be told, âThere are no more lackeys, we are all equal today.' Unabashed, she replied, âWell then, call my brother lackeys!' The one-size-fits-all âcommune' replaced the distinctions of hamlet, town and city. Meanwhile, the most ominous manifestation of equality was the newfangled instrument of capital punishmentâthe gleaming guillotineâwhich made its first appearance in the Place de Grève in April 1792.

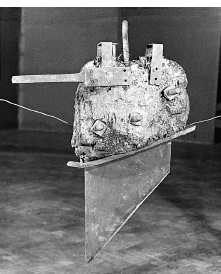

Historically, a protocol of execution meant that the supposed swiftness of beheading was the privilege of the well-bred criminal, while the riff-raff felons were subjected to burning, breaking on the wheel or hanging. Now the guillotine brought democracy to decapitation. As a new invention it captured the public imagination and was the talk of Paris; as a well-worn relic its fascination is undimmed. At the height of her fame in England, Marie allegedly bought the original guillotine blade and installed it in pride of place in the Chamber of Horrors. The

catalogue entry read, âThis relic was purchased by Madame Tussaud herself, together with the lunette, which held the victim's head in position and the chopper which the executioner kept at hand for use should the guillotine knife failâSanson the original executioner vouching for the authenticity of the articles which were then in possession of his grandson.' The whole was listed under the heading âThe most extraordinary relic in the world'.