Kate Berridge (15 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Nine days after the fall of the Bastille, the murder of Curtius and Marie's neighbour Foulon became their next grizzly subject.

Révolutions de Paris

reported this beheading with relish: the âsevered head separated far from his body was carried at the end of a pike through all the streets of Parisâ¦His body that was dragged through the mud and carried all over the place announced the terrible vengeance of a people rightly angry towards tyrants!' The unfortunate Foulon, a former finance minister, had made an ill-judged remark about food shortages, flippantly suggesting that people eat hay. Marie describes how, by way of revenge, a furious mob tracked him down at his country house and forced him back to the city, where he was subjected to a humiliating parade through the streets. Shamed and cheered with a collar of nettles round his neck, a bunch of thistles in his hand and a truss of hay tied at his back, he was finally dragged to the Hôtel de Ville and hanged. After death his head was hacked off and impaled on a pike cruelly brandished in front of his distraught son-in-law Berthier de Sauvigny, before he too was beheaded. Both heads were paraded on pikes, Foulon's gaping mouth mockingly stuffed with straw and dung. Other accounts of this well-documented double murder highlight the matter-of-fact tone of Marie's own recollection of it. She recalls the actions of the mob with no hint of her own feelings about either their barbarity or her having witnessed the

murder of a neighbour. There is no trace of revulsion. Even making allowances for the distance from which she recalled events in her memoirs, her impersonal tone is striking. In an understatement which contrasts sharply with other witnesses, she confines herself to the opinion, âThis event was a dreadful shock to all who wished well to their country, as it proved that the mob were too strong for the constitutional authorities.'

From locks to bed-linen there was a vast range of Bastille-themed merchandise

Grace Elliott, for example, was a less cool witness to the atrocity. Much of her memoir of the French Revolution reads as an innocently unselfconscious revelation from a privileged perspective. It is the Revolution seen from inside a carriage on the way back from the horse races at Vincennes, or from a private box at the theatre. It is revolution as inconvenience, traffic jam and interruption. Thus Foulon's beheading stops her shopping. She is en route to her jeweller's in the Rue Saint-Honoré when she encounters âa procession of French guards carrying Monsieur Foulon's head by the light of flambeaux. They thrust the head in my carriage and at the horrid sight I screamed and fainted away.' In his memoirs Chateaubriand describes graphically âthe horrid sight' that caused Grace Elliott to pass out. In the street outside his aristocratic mansion he had a chilling encounter with Foulon's killers, who âwere singing, capering, leaping to bring the pallid heads nearer to my own head. An eye in one head had been pushed from its socket and was dangling on the corpse's face, the pike sticking through the gaping mouth, the teeth clenched on the iron.' The visceral reality of Foulon's mangled body makes Marie's coolness seem even more striking.

Importantly, Chateaubriand's testimony suggests it might be right to challenge the widely held belief that casts were always made from the actual human remains. For maximum impact the wax heads needed to be easily identifiedâan unrecognizable mush would have no value. For a practised modeller, copying rather than casting from death seems a much more plausible method. Casting from the bloodstained original, while it became an important tool in Marie's marketing initiative later on, was not necessary in order to reproduce a convincingly ghoulish image. The head of Foulon was particularly popular, and promotional material for the exhibition made much of the fact that âthe blood seems to be streaming from it and running on

the ground'. Whereas Curtius and Marie had established their reputation with the allure of glamour, the new market centred on gore, and the voyeuristic lure of the brutalized bodyâbut sufficiently sanitized to appeal as an exhibit that people would pay to see. They controlled sensation rather as the media today edit and airbrush the atrocity pictures that come into the public domain.

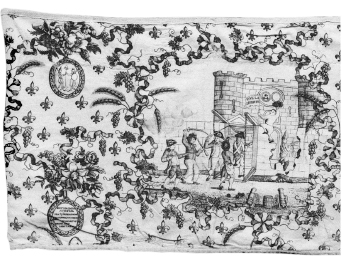

Lurid souvenirs of the bloodshed were but one facet of the new souvenir industry that emerged with the fall of the Bastille. There was a vast range of commemorative merchandise. From Bastille bonnets trimmed with fabric towers to Bastille shoe buckles, there were head-to-toe choices. There was even Bastille bed linen, with siege motifs that one would not have thought conducive to aristocrats getting a good night's sleep. And there were also Bastille panoramas, peep shows and plays. In fact there was no escape from the Bastille as a money-spinning theme. Long before its fall, this prison had exerted a great fascination for the public, with former prisoners turning their experiences into best-selling books. Simon Linguet's account of his two-year imprisonment was one of the most popular prison memoirs. First published in 1783, it reinforced the terror the place inspired, and its immense success meant that Linguet had the accolade of being featured in Curtius and Marie's collection. He kept alive preconceptions about the prison that made the public highly receptive to the versions of its fall that were sold in such a compelling variety of forms in July 1789.

The contract for its demolition won by the builder and stone-mason Pierre-François Palloy was a significant commercial coup. It is no surprise to learn that this self-styled âEntrepreneur de la démolition de la Bastille' was a good friend of Curtius. Like him, he exploited every commercial opportunity with panache. Under his guidance the Bastille was broken up and remade into an immense amount of imaginative merchandise. No stone was left unturned. Stone fragments became patriotic front-door steps; they were etched with maps, inscribed with words, and incorporated into mass-produced presentation packs, which also featured a seemingly endless supply of authentic keys. They were carved into busts of Mirabeau, and crafted into jewellery for all budgets. Poorer patriots displayed small chips in rings, but Madame de Genlis probably had difficulty

standing upright, such was the size of her Bastille bling. A large highly polished fragment was studded with the word âLiberté', spelled in gems, and surrounded by tricolour motifs in rubies, sapphires and diamonds, all entwined with laurels. And relics were also the basis of a âLiberty' museum which, after exhausting Parisian interest, Palloy sent on tour all over the country, like a portable theme park.

Macabre memorabilia also sold well. Metal fixtures and fittings were melted down and marketed as inkwells made from leg-irons, medallions from manacles. Commercial opportunism extended even to England, where, with an eye to the export market, designers responded rapidly to the dramatic turn of events in France. It was not just Marie and Curtius who profited from heads. The Wedgwood brothers announced, âWe are making Mr Necker's head of a size proper for snuffbox tops.' Elsewhere, the Duc d'Orléans's head was shrunk to fit on to gilt buttons, and both the people's heroes featured on a range of plaques and in endless plaster busts. Adaptability was the key requirement and, eager not to miss their moment with their range of Bastille medals, the Wedgwoods took artistic licence, merely modifying figures they had used the year before to commemorate the American wars of independence. The jasperware medallion advertised as showing the goddess of Liberty holding hands with France was in fact an ingenious bit of recycling, as evidenced in a letter by Josiah Wedgwood dated 29 July: âThe figure of Hope in the Botany Bay medal would come in exceedingly well for the figure of Liberty.'

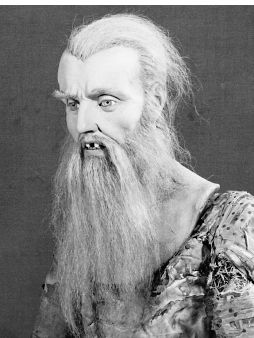

The public readily subscribed to the idea that in celebrating the storming of the Bastille they were celebrating the symbolic defeat of despotism. Newspapers fed them this angle: as one report put it, âThe dungeons are opened; liberty is given to innocent men, and to venerable old men surprised to see the light. For the first time, august and sacred liberty finally entered this abode of horrors, this dreadful asylum for despotism, monsters and crimes.' A barrage of products reinforced the liberation-propaganda bandwagon. But the most audacious piece of propaganda can be attributed to Marieâthe full-length wax figure named as the Comte de Lorges. The Wedgwoods' artistic licence with their Liberty medal pales compared to Marie's with this

composition, which is one of her most famous works. The figure of a wild-eyed, toothless old man with a long white beard is the perfect realization of the mental images that haunted the popular imagination about the victims of the

Ancien Régime

, incarcerated in dark dungeons called

oubliettes

, and forgotten by the outside world. The wax representation of the Comte is the fictional compensation for the factual deficiencies of the sorry cast of inmates who were released by the

vainqueurs

. Given that none of the prisoners was the raw material to inspire public sympathy, a journalistâCarraâdid what journalists still do: he abstracted from the facts a human-interest story that would engage. Published in September 1789, and entitled

Le Comte de Lorges prisonnier à la Bastille pendant 32 years enfermé en 1757 et mis en liberté 14 July 1789

, the slim volume was an instant success. This was the blueprint for Marie's reconstruction, the word made wax. Her figure, later seen by Charles Dickens in mid-nineteenth-century London, seems to have percolated in the novelist's imagination until being reborn as Dr Manette in

A Tale of Two Cities

(1859). The long beard and unkempt appearance which emphasize the impact of Manette's long-term isolation in cruel captivity echo very clearly de Lorges.

Marie is emphatic about de Lorges. She makes no mention of her part in the wax likenesses of the first victims of the Revolution, but de Lorges is the first figure since the outbreak of the Revolution for which she takes full credit. She describes how the Comte was discovered with other prisoners in dark dungeons beneath the prison. The âmost remarkable' among them, she says, âhe was brought to her that she might take a cast from his face, which she completed. It is a whole-length resemblance taken from life. He had been thirty years in the Bastille and when liberated from it, having lost all relish for the world, requested to be reconducted to his prison and died a few weeks after his emancipation.' Her earliest posters advertising the exhibition when she came to England also made reference to him, and in catalogues she even tackled those sceptical about the true history of this frail old man by reasserting her personal acquaintance: âExistence of this unfortunate man in the Bastille has by some been doubted, but Madame Tussaud is herself a witness of his being taken out of that prison July 14, 1789.' There is more than a hint of Manette in her catalogue description of how âthe poor man unused to Liberty for 30

years seemed to be in a new world' and âfrequently with tears he would beg to be restored to his dungeon.' The figure was often singled out for praise in reviews of the exhibition: in Liverpool, for example, the edition of the local paper for 14 April 1821 declared, âThe Count de Lorges is a fine piece of physiognomy.'