Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (28 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

That preparation extended to dossiers on the opposition. Players came to know their opponents so well that it was said they could recognise them from Herrera’s descriptions without recourse to photographs. Suárez, who became the world’s most expensive player when he joined Inter from Barca in 1961, regarded Herrera’s approach as unprecedented. ‘His emphasis on fitness and psychology had never been seen before. Until then, the manager was unimportant. He virtually slapped the best players, making them believe they weren’t good enough, and praised the others. They were all fired up - to prove him right or wrong.’

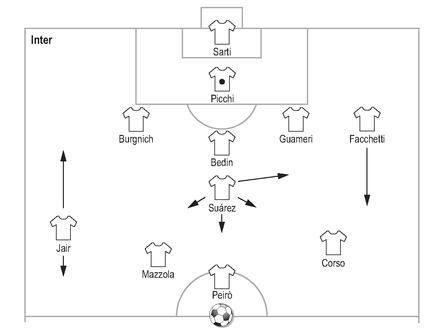

Inter hammered Atalanta 5-1 in Bergamo in Herrera’s first game in charge, won their next away game 6-0 at Udinese, then put five past Vicenza. They ended up third in the table, but scored seventy-three goals in thirty-four games - more than anybody but the champions Juventus. They were second the following year, but that was not enough for Moratti. That summer, the president even invited Edmondo Fabbri to the Appiano Gentile to offer him Herrera’s job, only to have second thoughts at the last minute and send him home, telling Herrera he had one more season to deliver the success he had promised. It was then that Herrera decided he had to change. ‘I took out a midfielder and put him sweeping behind the main defenders, liberating the left-back to attack,’ he said. ‘In attack, all the players knew what I wanted: vertical football at great speed, with no more than three passes to get to the opponents’ box. If you lose the ball playing vertically, it’s not a problem - but lose it laterally and you pay with a goal.’

Picchi, who scored just once in his Serie A career, proved a diligent sweeper, described by Brera as ‘a defensive director … his passes were never random, his vision was superb’. Aristide Guarneri operated as a stopper central-back, with Burgnich, the right-back, sitting alongside him. ‘By this point,’ said Maradei, ‘many teams were employing a

tornante

, usually the right-winger, which meant that effectively the left-winger was the more attacking, often cutting inside to shoot on goal. Many great Italian forwards - most notably Gigi Riva and Pierino Prati - started like that.’

La Grande Inter

That gave the left-back, Giacinto Facchetti, who had arrived at the club as a forward, greater licence to push forwards, because the man he was marking tended to sit deeper. ‘Jair was in front of Burgnich,’ Maradei went on. ‘He was not a great defender, but dropped deep because he was the kind of player who liked to run at people and needed space in front of him. On the left, in front of Facchetti, you had Corso, a very creative player, not the quickest or the most attacking, but a man capable of unlocking opposing defences. He was the link man with the front guys. Carlo Tagnin and, later, Gianfranco Bedin, sat in front of the defence and did most of the running and defending. Alongside him was Suárez who had great vision and the ability to hit very accurate long passes. That was the typical way Inter restarted after winning possession. They would either get the ball to Jair, who would run into space, or leave it for Suárez, who would hit it from deep over the midfield for Mazzola or the centre-forward - Beniamino Di Giacomo or Aurelio Milani, neither of whom was particularly gifted - or Jair cutting in from the right to run on to.’

Facchetti was the key, and it was he who gave Herrera his best defence against the accusations of negativity. ‘I invented

catenaccio

,’ Herrera said. ‘The problem is that most of the ones who copied me copied me wrongly. They forgot to include the attacking principles that my

catenaccio

included. I had Picchi as sweeper, yes, but I also had Facchetti, the first full-back to score as many goals as a forward.’ That is a slight exaggeration - Faccchetti only once got into double figures in the league - but his thrusts down the left give the lie to those who suggest Herrera habitually set up his team with a

libero

and four defensive markers.

The effectiveness of Herrera’s system could hardly be questioned. They won Serie A in 1963, 1965 and 1966 - missing out in 1964 only after losing a playoff to Bologna, were European champions in 1964 and 1965 and reached the final again in 1967. Success alone, though, does not explain why Shankly so hated Herrera and

catenaccio

, even allowing for their perceived defensiveness. The problem was the skulduggery that went along with it.

Even at Barcelona there had been dark rumours. Local journalists who felt aggrieved by Herrera’s abrasive manner began referring to him as ‘the pharmacy cup coach’ and, although players of the time deny the allegations, they are given credence by what followed. ‘He was serious at his job, but had a good sense of humour, and knew how to get the best out of his players,’ said the Spain midfielder Fusté, who came through Barcelona’s youth ranks during Herrera’s reign. ‘All that stuff about him giving us all drugs is all lies. What he was, was a good psychologist.’

That he certainly was, but the suggestion he was also a decent pharmacologist never went away. Most notorious were the claims made in his autobiography by Ferruccio Mazzola, Sandro’s younger and less talented brother. ‘I’ve seen with my eyes how players were treated,’ he said. ‘I saw Helenio Herrera providing pills that were to be placed under our tongues. He used to experiment on us reserve players before giving them to the first-team players. Some of us would eventually spit them out. It was my brother Sandro that suggested that if I had no intention of taking them, to just run to the toilet and spit them out. Eventually Herrera found out and decided to dilute them in coffee. From that day on “

Il Caffè Herrera

” became a habit at Inter.’ Sandro vehemently denied the allegations, and was so angered by them he subsequently broke off relations with his brother, but the rumours were widespread. Even if they were not true, their proliferation further sullied the image of the club, and the fact that they were so widely believed is indicative of how far people thought Herrera would go in his pursuit of victory.

At Inter, tactics, psychology and ethos became commingled. Herrera might have had a case when he argued that his side’s tactical approach was not necessarily defensive, but it can hardly be denied that there was a negativity about their mentality. In

The Italian Job

, Gianluca Vialli and Gabriele Marcotti speak at length of the insecurity that pervades Italian football; in Herrera’s Inter it revealed itself as paranoia and a willingness to adopt means that would have appalled Chapman, never mind an idealist like Hugo Meisl. Brera, eccentrically, always maintained that Italians had to play defensive football because they lacked physical strength. Gamesmanship became a way of life. Ahead of the 1967 European Cup final against Celtic, for instance, Herrera arrived in Glasgow by private jet to watch Celtic play Rangers at Ibrox. Before leaving Italy, he had offered to give Jock Stein a lift back so he could see Inter’s match against Juventus. Stein, wisely, did not cancel the tickets he had booked on a scheduled flight, and his caution was justified when Herrera withdrew the invitation on arrival in Glasgow, saying the plane was too small for a man of Stein’s girth. The taxi and tickets Inter had promised to lay on in Turin similarly failed to materialise, and Stein ended up seeing the game only because a journalist persuaded gatemen to admit him with a press card.

They were minor examples, but even leaving aside the accusations of drug-taking and match-fixing, there were times Herrera appeared monstrously heartless. When Guarneri’s father died the night before a match against AC Milan, for instance, Herrera kept the news from him until after the game. In 1969, when he had left Inter and become coach of Roma, the forward Giulano Taccola died under Herrera’s care. He had been ill for some time and, after an operation to remove his tonsils brought no relief, further medical examination revealed he had a heart murmur. Herrera played Taccola in a Serie A game at Sampdoria, but he lasted just forty-five minutes before having to be taken off. A fortnight later Herrera had him travel with the squad to Sardinia for an away game against Cagliari. He had no intention of playing him, but on the morning of the game, he made Taccola train on the beach with the rest of the squad, despite a cold and gusting wind. Taccola watched the match from the stands, collapsed in the dressing room after the game and died a few hours later.

Then there were the allegations that Herrera habitually rigged games. The suggestions Inter manipulated referees first surfaced - at international level at least - after their European Cup semi-final against Borussia Dortmund in 1964. They had drawn the first leg in Germany 2-2, and won the return at the San Siro 2-0, a game in which they were significantly helped by an early injury to Dortmund’s Dutch right-half Hoppy Kurrat, caused by a kick from Suárez. The Yugoslav referee Branko Tesanić took no action. That might have passed without notice, but then a Yugoslav tourist met Tesaniç on holiday that summer, and claimed the official had told him that his holiday had been paid for by Inter.

In the final in Vienna, Inter met Real Madrid. Tagnin was detailed to man-mark Di Stefano, Guarneri neutralised Puskás, and two Mazzola goals gave them a 3-1 win. The Monaco forward Yvon Douis had criticised Inter’s approach earlier in the tournament, and Madrid’s Lucien Müller echoed his complaints after the final. Herrera simply pointed to the trophy. They were more attacking in Serie A the following season, scoring sixty-eight goals, but they had lost none of their defensive resolve. Leading 3-1 from the first leg of their quarter-final against Rangers, they conceded after seven minutes at Ibrox, but held out superbly. That was the legitimate side of

catenaccio

; what followed in the semi-final against Liverpool was rather less admirable.

Liverpool took the first leg at Anfield 3-1, after which, Shankly said, an Italian journalist told him, ‘You will never be allowed to win.’ They weren’t. They were kept awake the night before the game by rowdy local fans surrounding their hotel - a complaint that would become common in European football - but it was when the game started that it became apparent something was seriously wrong. Eight minutes in, Corso struck an indirect free-kick straight past the Liverpool goalkeeper Tommy Lawrence, and Ortiz de Mendibil, the Spanish referee, allowed the goal to stand. Two minutes later Joaquin Peiro pinched the ball from Lawrence as he bounced it in preparation for a kick downfield, and again De Mendibil gave the goal. Facchetti sealed the win with a brilliant third.

De Mendibil was later implicated in the match-fixing scandal uncovered by Brian Glanville and reported in the

Sunday Times

in 1974, in which Dezso Solti, a Hungarian, was shown to have offered $5,000 and a car to the Portuguese referee Francisco Lobo to help Juventus through the second leg of their European Cup semi-final against Derby County in 1973. Glanville believes he was in the pay of Juventus’s club secretary, Italo Allodi, who had previously worked at Inter. He showed that the games of Italian clubs in Europe tended to be overseen by a small pool of officials, and that when they were, those Italian clubs were disproportionately successful. In so doing, Glanville simply proved what anecdotal evidence had suggested all along: referees were being paid off. It was that that Shankly could not forgive.

The 1965 final against Benfica - played, controversially, at the San Siro - was almost a case study in the classic Hererra match. Inter took the lead three minutes before half-time as Jair’s shot skidded through Costa Pereira in the Benfica goal, but even after he had been injured, leaving his side down to ten men and with Germano, a defender, in goal, even though they were effectively playing at home, Inter continued to defend, happy to protect their lead. Was it pragmatism, or was it that, for all Herrera’s efforts at building self-confidence, they didn’t quite have faith in their own ability? Was it even that they had come to rely not just on their own efforts, but on those of the referee?

Benfica, losing their second final in three years, blamed the curse of Guttmann, but the truth was that their attacking approach had become outmoded; at club level at least,

catenaccio

- by means both justified and illegitimate - had superseded the remnants of the classic Danubian style that still lingered in their 4-2-4. When all else was equal, though - when referees had not been bought off -

catenaccio

could still come unstuck against talented attacking opposition. Inter won the

scudetto

again in 1965-66, but were beaten by Real Madrid in the semi-final of the European Cup. The referee for the second leg of that tie was the Hungarian György Vadas. He officiated with scrupulous fairness as Madrid secured a 1-1 draw that took them through by a 2-1 aggregate, but years later he revealed to the Hungarian journalist Peter Borenich that he too had been approached by Solti. He, unlike an unknown number of others, turned Inter down.

It was the following year, though, that Herrera’s Inter disintegrated, and yet the season had begun superbly, with a record-breaking run of seven straight victories. By mid-April they were four points clear of Juventus at the top of Serie A, and in Europe had had their revenge on Real Madrid, beating them 3-0 on aggregate in the quarter-finals. And then something went horribly wrong. Two 1-1 draws against CSKA Sofia in the semi-final forced them to a playoff - handily held in Bologna after they promised the Bulgarians a three-quarter share of the gate-receipts - and although they won that 1-0, it was as though all the insecurities, all the doubts, had rushed suddenly to the surface. They drew against Lazio and Cagliari, and lost 1-0 to Juventus, reducing their lead at the top to two points. They drew against Napoli, but Juve were held at Mantova. They drew again, at home to Fiorentina, and this time Juve closed the gap, beating Lanerossi Vicenza. With two matches of their season remaining - the European Cup final against Celtic in Lisbon, and a league match away to Mantova - two wins would have completed another double, but the momentum was against them.