Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (24 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

In October 1981, Lobanovskyi’s Dynamo beat Zenit Leningrad 3-0 to win the Soviet title for the tenth time. A piece in

Sportyvna Hazeta

eulogising their fluidity of movement in that game and over that season makes the progression clear: ‘Viktor Maslov dreamt once of creating a team that could attack with different groups of players. For instance [Anatoliy] Byshovets and [Vitaliy] Khmelnytskyi would start the match battering the opposition defence, but then at some point they could drop back into midfield and their places could be taken by, say, Muntyan and Serebryanykov. But at that time such a way of playing didn’t come together. It is an achievement of the present day.’

And yet every now and again Maslov’s players did, by chance or by instinct, switch positions. ‘The 4-4-2 system introduced by Grandad was only a formal order; in the course of the game there was complete inter-changeability,’ Szabo said. ‘For example, any defender could press forward without fear because he knew that a team-mate would cover him if he were unable to return in time. Midfielders and forwards could allow themselves a much wider variety of actions than before. This team played the prototype of Total Football. People think it was developed in Holland, but that is just because in Western Europe they didn’t see Maslov’s Dynamo.’

Maslov was eventually sacked in 1970 as Dynamo slipped to seventh in the table. In 1966, with several members of the squad away at the World Cup, he had managed to maintain Dynamo’s league form because of the emergence of a number of players from the youth team. In 1970, he found no such reserves. ‘Any coach’s fate depends on results,’ said the defender Viktor Matviyenko. ‘After the spring half of the season we were second in the table, and I’m sure Grandad would have kept his job if we’d have maintained that position to the end. He just needed to repeat the experience of 1966 when the outstanding youth players kept the players who had come back from England out of the squad. It was a similar situation in 1970. The Dynamo players who were at the World Cup in Mexico were absent for a month and a half, and played only a couple of games. They lost more there than they gained simply because they had no match practice. But Grandad didn’t take it into account and brought straight back players who had lost their sharpness, and so we began to fall in the standings.’

Perhaps that was understandable. Maslov had, after all, been at the club for seven years, and the feeling was that he had perhaps gone stale. The manner of his dismissal, though, leaves a sour taste; Koman called it ‘the most disgraceful episode in Dynamo’s history’. It was decided that it was more politically expedient to dismiss him away from Kyiv, and so when, towards the end of the 1970 season, Dynamo travelled to Moscow for a game against CSKA, they were joined by Mizyak, the deputy head of the Ukrainian SSR State Sport Committee. He usually had a responsibility for winter sports, but in the Hotel Russia before the game, he made the official announcement that Maslov had been removed from his position.

With Maslov sitting in the stand and no replacement appointed, Dynamo lost 1-0. After the game, as the team bus carried the players to the airport for the flight back to Kyiv, they stopped at the Yugo-Zapadnaya metro station and dropped Maslov off. As he walked away, he looked back over his shoulder and slowly raised a hand in farewell. ‘If I hadn’t seen it myself,’ Koman said, ‘I’d never have believed a giant like Maslov could have wept.’

Maslov returned to Torpedo, and won the cup with them, and then had a season in Armenia with Ararat Yerevan, where he again won the cup, but he never had the resources - or perhaps the energy - to repeat the successes of Dynamo. By the time he died, aged sixty-seven, in May 1977, Lobanovskyi, the player he had exiled, was ensuring his legacy lived on. His impact was perhaps less direct than that of Jimmy Hogan, but no coach since has been so influential.

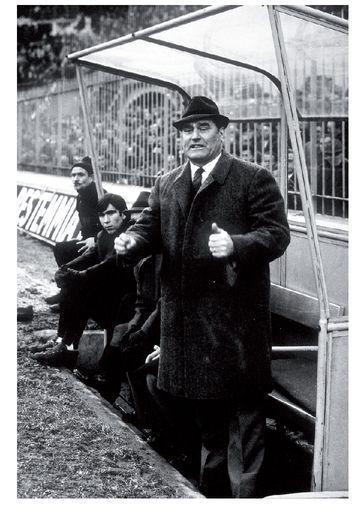

Nereo Rocco, one of the pioneers of

catenaccio

(

PA Photos

)

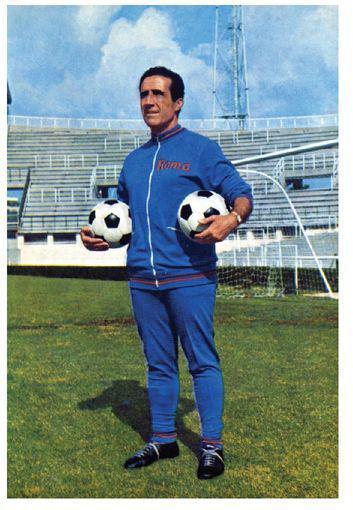

Helenio Herrera, the grand wizard of

catenaccio

(

PA Photos

)

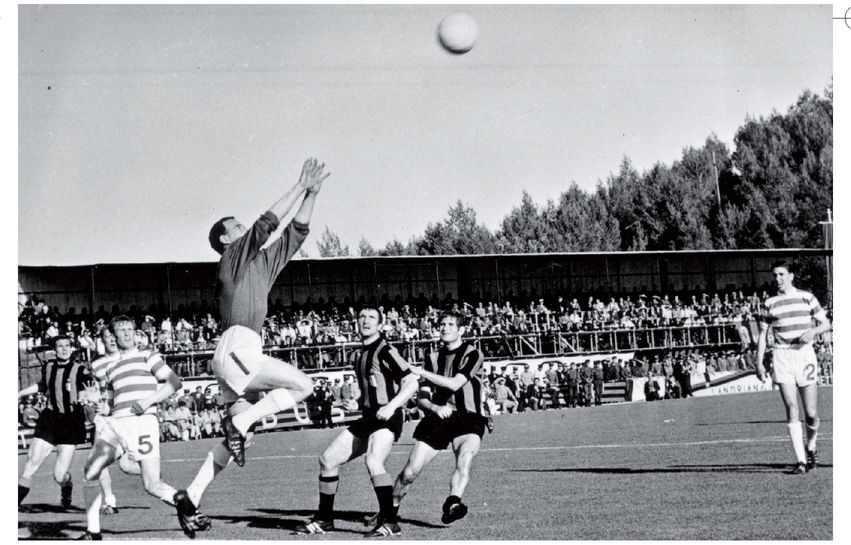

Ronnie Simpson claims a cross as Celtic beat Inter in the 1967 European Cup final (

Getty Images

)

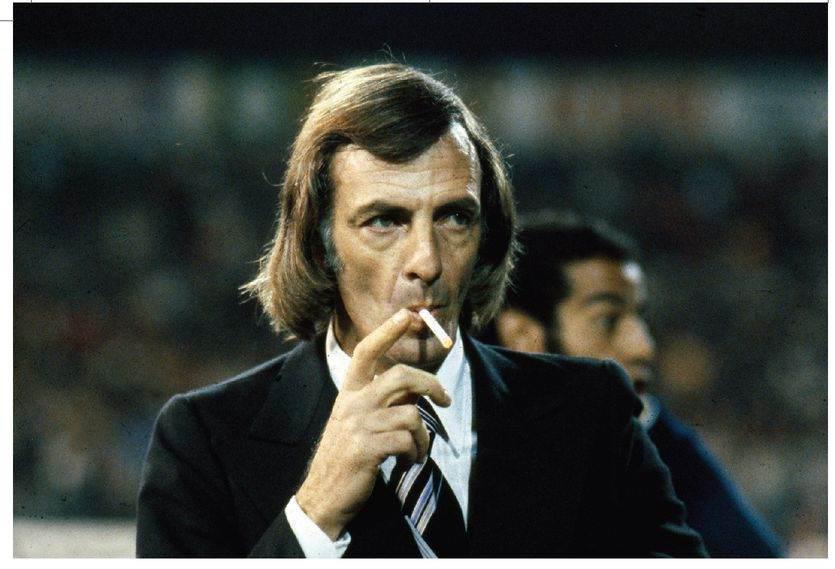

César Luis Menotti, who won the World Cup with his reinterpretation of

la nuestra

… (

Getty Images

)

… and his ideological opposite, Carlos Bilardo, who won the World Cup after devising 3-5-2 (

PA Photos

)

Rinus Michels on the Dutch bench at the 1974 World Cup … … and Johan Cruyff, with whom he developed Total Football (both pics ©

Getty Images

)

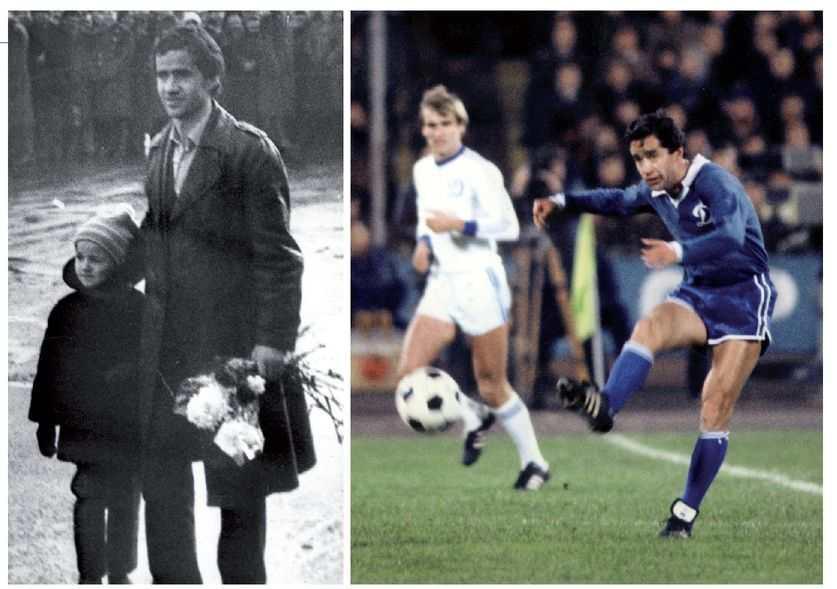

The two schools of Soviet football, Eduard Malofeev (left) and Valeriy Lobanovskyi (right)

(Igor Utkin

)

Sacha Prokopenko: playboy and player (both pics ©

Dinamo Sports Society

)

Graham Taylor, who introduced pressing to the English game, and Elton John, his chairman at Watford (

Getty Images

)