Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (25 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Arrigo Sacchi makes a point to Marco van Basten (

PA Photos

)

Pelé heads home the opener in the 1970 World Cup final (

Getty Images

)

Mario Zagallo, the coach who oversaw the greatest display of football’s pre-systemic age (

Getty Images

)

The last of the old-style play makers, Juan Roman Riquelme … (

Rex Pictures

)

… and Luka Modrić, the first of the new (

PA Photos

)

Chapter Ten

Catenaccio

∆∇ There is no tactical system so notorious as

catenaccio

. To generations, the word - which means ‘chain’, in the sense of a chain on a house door - summons up Italian football at its most paranoid, negative and brutal. So reviled was it in Britain that when Jock Stein’s Celtic beat Helenio Herrera’s Internazionale, its prime exponents, in the European Cup final of 1967, the Liverpool manager Bill Shankly congratulated him by insisting the victory had made him ‘immortal’. It later emerged that he had instructed two Celtic coaches to sit behind the Inter bench and abuse Herrera throughout the game. Herrera would always insist he was misunderstood, that his system, like Herbert Chapman’s, had acquired an unfavourable reputation only because other, lesser sides attempting to copy his team’s style implemented it so badly. That remains debatable but, sinister as

catenaccio

became, its origins were homely.

It began in Switzerland with Karl Rappan. Softly-spoken, understated and noted for his gentle dignity, Rappan was born in Vienna in 1905, his professional career as a forward or attack-minded half coinciding with the golden age of Viennese football in the mid-to late twenties. So rooted was he in coffee-house society that later in life he ran the Café de la Bourse in Geneva. He was capped for Austria and won the league with Rapid Vienna in 1930, after which he moved to Switzerland to become player-coach at Servette. His players there were semi-professional and so, according to Walter Lutz, the doyen of Swiss sportswriting, Rappan set about devising a way of compensating for the fact that they could not match fully professional teams for physical fitness.

‘With the Swiss team tactics play an important role,’ Rappan said in a rare interview with

World Soccer

magazine shortly before the World Cup in 1962. ‘The Swiss is not a natural footballer, but he is usually sober in his approach to things. He can be persuaded to think ahead and to calculate ahead.

‘A team can be chosen according to two points of view. Either you have eleven individuals, who owing to sheer class and natural ability are enabled to beat their opponents - Brazil would be an example of that - or you have eleven average footballers, who have to be integrated into a particular conception, a plan. This plan aims at getting the best out of each individual for the benefit of the team. The difficult thing is to enforce absolute tactical discipline without taking away the players’ freedom of thinking and acting.’

His solution, which was given the name

verrou

- bolt - by a Swiss journalist, is best understood as a development from the old 2-3-5 - which had remained the default formation in Vienna long after Chapman’s W-M had first emerged in England. Rather than the centre-half dropping in between the two full-backs, as in the W-M, the two wing-halves fell back to flank them. They retained an attacking role, but their primary function was to combat the opposition wingers. The two full-backs then became in effect central defenders, playing initially almost alongside each other, although in practice, if the opposition attacked down their right, the left of the two would move towards the ball, with the right covering just behind, and vice versa. In theory, that always left them with a spare man - the

verouller

as the Swiss press of the time called him, or the

libero

as he would become - at the back.

The system’s main shortcoming was that it placed huge demands on the centre-half. Although on paper the formation - with four defenders, a centre-half playing behind two withdrawn inside-forwards, and a string of three across the front - looks similar to the modern 4-3-3 as practised by, say, Chelsea in José Mourinho’s first two seasons at the club, the big difference is how advanced the wingers were. They operated as pure forwards, staying high up the pitch at all times rather than dropping back to help the midfield when possession was lost. That meant that when the

verrou

faced a W-M, the front three matched up in the usual way against the defensive three and inside-forwards took the opposition’s wing-halves, leaving the centre-half to deal with two inside-forwards. This was the problem sides playing a

libero

always faced: by creating a spare man in one part of the pitch, it necessarily meant a shortfall elsewhere.

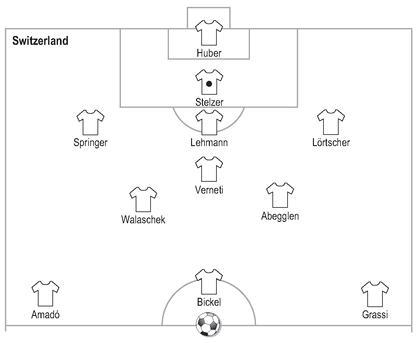

Rappan’s Verrou, 1938

Against a 2-3-5, the situation was even worse. The side playing the

verrou

had a man over at both ends of the pitch, but that meant the centre-half was trying to cope not only with the opposing inside-forwards, but also the other centre-half. That was all but impossible, so Rappan’s team tended to drop deep, cede the midfield to their opponents and, by tight marking, present a solid front to frustrate them so they ended up passing the ball fruitlessly sideways. As the system developed, the burden was taken off the centre-half as an inside-forward gradually fell back to play alongside him, but the more striking change was that made to the defensive line as one of the two full-backs (that is, the

de facto

centre-backs) dropped behind the other as an orthodox sweeper.

Rappan won two league titles with Servette and five more with Grasshoppers, whom he joined in 1935, but it was his successes with the Switzerland national side that really demonstrated the efficacy of his system. Rappan became national coach in 1937, with a brief to lead Switzerland into the 1938 World Cup. At the time, Switzerland were regarded as the weakest of the central European nations, and their record in the Dr Gerö Cup was correspondingly poor: played 32, won 4, drawn 3, lost 25. Using the

verrou

, though, they beat England 2-1 in a pre-World Cup friendly, and then beat Germany - by then encompassing Austria - in the first round of the tournament itself, before going down 2-0 to Hungary. That was an honourable exit - far more than Switzerland had achieved previously, but the

verrou

was considered little more than a curiosity; perhaps a means for lesser teams to frustrate their betters, but no more.

Perhaps not surprisingly given the rethink of defensive tactics necessitated by Boris Arkadiev’s organised disorder, a similar system sprang up, seemingly independently, a few years later in Russia. Krylya Sovetov Kuibyshev (now Samara), a team backed by the Soviet Air Force, were founded in 1943, winning promotion to the Supreme League in 1945. They soon became noted for their defensive approach, specifically a tactic known as the

Volzhskaya Zashchepka

- the ‘Volga Clip’. It may not have been so flexible as the

verrou

, and it was a development of the W-M rather than the 2-3-5, but the basic principle was the same, with one of the half-backs dropping deep, allowing the defensive centre-half to sweep behind his full-backs.

Its architect was Krylya’s coach, Alexander Kuzmich Abramov. ‘Some people were amazed because he wasn’t a football professional in the usual sense of the term,’ the former Krylya captain Viktor Karpov said. ‘He came from the world of gymnastics, so maybe because of that he wasn’t directed by dogma, but had his own opinions on everything. He paid a lot of attention to gymnastic exercises, using training sessions to improve our coordination. An hour could go by and you wouldn’t touch the ball, yet somehow it helped us to be more skilful. Kuzmich made us think on the pitch. Before each game he would gather the team together and we would discuss the plan for the match. As far as I’m aware, other coaches didn’t do this.

‘How we played depended on our opponents. If we were playing Dinamo, for instance, and their forward line was Trofimov, Kartsev, Beskov, Soloviov, Ilyin, then of course you had to take measures to counter such a star quintet. At that time most teams played with three defenders, but our half-backs would help them out more. Usually that meant me and [the left-half] Nikolai Pozdyanakov.

‘We didn’t man-mark as such. We tried to play flexibly, and the system meant that the range of action of each player became broader. Sometimes a reserve player would come in and he would try to chase his opponent all over the pitch - his man would go and have a drink and our novice would follow him. We would laugh at players like that, because we regulars had been taught that we should act according to the circumstances.’

As when Nikolai Starostin first had his brother operate as a third back, there were those who protested at Abramov’s innovation, seeing it as a betrayal of the ideals of Russian football, but gradually the system became accepted, as Lev Filatov puts it in

About Everything in an Orderly Manner

, as ‘the right of the weak’. The forward Viktor Voroshilov, who also captained the side under Abramov, was scathing of the system’s critics. ‘Let’s say we were playing against CDKA,’ he said. ‘In attack they had Grinin, Nikolaev, Fedotov, Bobrov and Doymin. So we’re supposed to venture upfield? That’s why we played closer to our own goal. Once against Dinamo Moscow we opened up, [their coach] Mikhey Yakushin outwitted us and we lost 5-0.’

The Volga clip’s success as a spoiling tactic could hardly be faulted. After winning just three of twenty-two games in 1946, and finishing tenth of the twelve top-flight sides, Krylya climbed to seventh of thirteen in 1947, recording a famous win over Dinamo Moscow. They beat them again in 1948 and, in 1949, they won 1-0 both home and away against CDKA. ‘Their famous opponents tried to make it a game,’ Filatov wrote. ‘They combined in passing moves, won corners and free-kicks, but every time they were denied and the ball flew into the sky or on to the running track that ran round the pitch. Eventually their spirits dropped, because they realised they were banging their heads against a wall.’

Essentially, though, the clip was seen as a small team’s tactic, a means of countering superior sides rather than a pro-active strategy in its own right. Krylya finished fourth in 1951 and got to the Soviet Cup final two years later, and Karpov recalls man-marking the giant Hungarian forward Gyula Szilágyi as the USSR employed the clip to win a B-international 3-0 in Budapest in 1954, but it largely remained confined to Krylya. The bolt had to move to Italy before it became mainstream.