Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (43 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Presumably because of their historical lack of success, Olsen’s philosophy seems to have been more widely accepted in Norway than the long-ball game was elsewhere. As Larson notes, under him Norwegian fans became used to dealing in ‘goal-chances’: a 1-1 draw in a World Cup qualifier at home to Finland in 1997, for instance, did not prompt anguish because it was recognised that they had won 9-2 on chances; they then beat the same opponents away, having won just 7-5 on chances. The issue, though, as it should have been for Reep and Hughes, is the quality of the chances. An open goal from six yards is not the same as a bicycle kick from thirty: not all chances are equal.

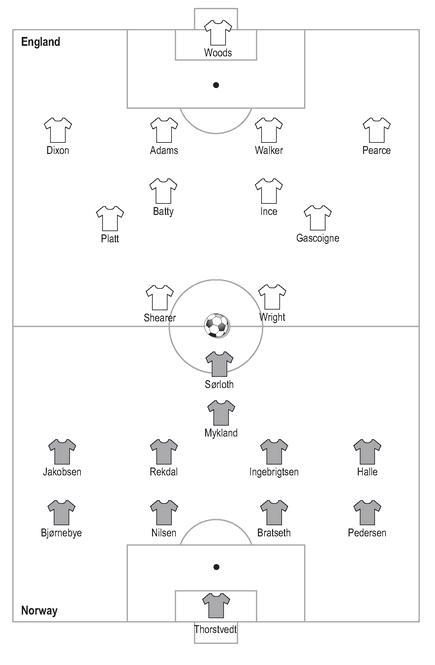

England 1 Norway 1, Wembley, World Cup Qualifier, 14 October 1992

More significant was the qualifying campaign for the 1994 World Cup. When Norway beat England 2-1 in qualifying for the 1982 World Cup, it was such a shock it sent the radio commentator Børge Lillelien into barely coherent delirium: ‘Lord Nelson, Lord Beaverbrook, Sir Winston Churchill, Sir Anthony Eden, Clement Attlee, Henry Cooper, Lady Diana,

vi har slått dem alle sammen, vi har slått dem alle sammen

[we have beaten them all, we have beaten them all]. Maggie Thatcher, can you hear me? Maggie Thatcher [...] your boys took a hell of a beating! Your boys took a hell of a beating!’ When Norway beat England 2-0 in Oslo in 1993, a game that also produced a notorious catchphrase - Taylor’s ‘do I not like that’ - it was entirely predictable.

The more damaging result, though, had been the 1-1 draw at Wembley, a game England had dominated and led until Kjetil Rekdal, a defensive midfielder, thrashed a 30-yard drive into the top corner fourteen minutes from time. This, for the dice-rollers, was vindication. Did Rekdal really think he would score? Did he send screamers like that flying in on a regular basis? Or was he simply, as Hughes would have urged him to do, buying another ticket for the raffle? Either way, random chance, as Reep no doubt saw it, had its revenge on Taylor.

Chapter Sixteen

The Coach Who Wasn’t a Horse

∆∇ It was AC Milan’s success in Europe in the sixties that introduced the

libero

as the Italian default and, a quarter of a century later, it was AC Milan’s success in Europe that killed it off. Hamburg’s victory over Juventus in the 1983 European Cup final may have alerted coaches and pundits to the flaws in

il giocco all’Italiano

, but Juventus’s 1-0 victory over Liverpool amid the horror of Heysel two years later confirmed its predominance.

There were efforts to move away from the

libero

and man-marking, but they were isolated. Luis Vincio introduced zonal defence at Napoli in 1974, but the experiment fizzled out, and then the former Milan forward Nils Liedholm employed a form of zonal marking with Roma, a tactic that got his side to the European Cup final in 1984. He moved on to Milan, but it was only after Arrigo Sacchi had succeeded him in 1987 that Italian football was awakened to the possibilities of abandoning man-marking altogether and adopting an integrated system of pressing. ‘Liedholm’s zone wasn’t a real zone,’ Sacchi said. ‘My zone was different. Marking was passed on from player to player as the attacking player moved through different zones. In Liedholm’s system, you started in a zone, but it was really a mixed zone, you still man-marked within your zone.’ It is probable no side has ever played the zonal system so well as Sacchi’s Milan. Within three years, he had led them to two European Cups and yet, when he took charge, he was a virtual unknown and the club appeared to be stagnating.

Born in Fusignano, a community of 7,000 inhabitants in the province of Ravenna, Sacchi loved football, but he couldn’t play it. He worked as a salesman for his father’s shoe factory and, as it became apparent he wasn’t even good enough for Baracco Luco, his local club, he began coaching them. Not for the last time, he faced a crisis of credibility. ‘I was twenty-six, my goalkeeper was thirty-nine and my centre-forward was thirty-two,’ he said. ‘I had to win them over.’

Even at that stage, though, for all the doubts he faced, Sacchi had very clear ideas about how the game should be played. ‘As a child I loved the great sides,’ he said. ‘As a small boy, I was in love with Honvéd, then Real Madrid, then Brazil, all the great sides. But it was Holland in the 1970s that really took my breath away. It was a mystery to me. The television was too small; I felt like I need to see the whole pitch fully to understand what they were doing and fully to appreciate it.’

Those four sides were all great passing sides, teams based around the movement and interaction of their players. Honvéd, Real Madrid and Brazil - with varying degrees of self-consciousness - led the evolution towards system; the Holland of Rinus Michels were one of the two great early exponents of its possibilities. Tellingly, when watching them, the young Sacchi wanted to see not merely the man on the ball, not merely what most would consider the centre of the action, but also the rest of the team; he approached the conclusion Valeriy Lobanovskyi had come to, that the man out of possession is just as important as the man in possession, that football is not about eleven individuals but about the dynamic system made up by those individuals.

Most simply, though, Sacchi warmed to attacking sides, and that alone was enough to set him apart from the mainstream of a football culture conditioned by the legacy of Gipo Viani, Nereo Rocco and Helenio Herrera. ‘When I started, most of the attention was on the defensive phase,’ Sacchi said. ‘We had a sweeper and man-markers. The attacking phase came down to the intelligence and common sense of the individual and the creativity of the number ten. Italy has a defensive culture, not just in football. For centuries, everybody invaded us.’

It was that that led Gianni Brera to speak of Italian ‘weakness’, to argue that defensive canniness was the only way they could prosper, an idea reinforced by the crushing defeat of the Second World War, which seemed to expose the unreliability of the militarism that had underlain Vittorio Pozzo’s success in the Mussolini era. Sacchi, though, came to question such defeatism as he joined his father on business trips to Germany, France, Switzerland and the Netherlands. ‘It opened my mind,’ Sacchi said. ‘Brera used to say that Italian clubs had to focus on defending because of our diets. But I could see that in other sports we would excel and that our success proved that we were not inferior physically. And so I became convinced that the real problem was our mentality, which was lazy and defensive.

‘Even when foreign managers came to Italy, they simply adapted to the Italian way of doing things; maybe it was the language, maybe it was opportunism. Even Herrera. When he first arrived, he played attacking football. And then it changed. I remember a game against Rocco’s Padova. Inter dominated. Padova crossed the halfway line three times, scored twice and hit the post. And Herrera was crucified in the media. So what did he do? He started playing with a

libero

, told [Luis] Suárez to sit deep and hit long balls and started playing counterattacking football. For me,

La Grande Inter

had great players, but it was a team that had just one objective: winning. But if you want to go down in history you don’t just need to win, you have to entertain.’

That became an abiding principle, and Sacchi seems very early to have had an eye on posterity, or at least to have had a notion of greatness measured by something more than medals and trophies. ‘Great clubs have had one thing in common throughout history, regardless of era and tactics,’ he said. ‘They owned the pitch and they owned the ball. That means when you have the ball, you dictate play and when you are defending, you control the space.

‘Marco van Basten used to ask me why we had to win and also be convincing. A few years ago,

France Football

made their list of the ten greatest teams in history. My Milan was right up there.

World Soccer

did the same: my Milan was fourth, but the first three were national teams - Hungary ’54, Brazil ’70 and Holland ’74. And then us. So I took those magazines and told Marco, “This is why you need to win and you need to be convincing.” I didn’t do it because I wanted to write history. I did it because I wanted to give ninety minutes of joy to people. And I wanted that joy to come not from winning, but from being entertained, from witnessing something special. I did this out of passion, not because I wanted to manage Milan or win the European Cup. I was just a guy with ideas and I loved to teach. A good manager is both screenwriter and director. The team has to reflect him.’

The sentiment is one with which Jorge Valdano, these days the eloquent philosopher prince of aesthetic football, is in full agreement. ‘Coaches,’ he said, ‘have come to view games as a succession of threats and thus fear has contaminated their ideas. Every imaginary threat they try to nullify leads them to a repressive decision which corrodes aspects of football such as happiness, freedom and creativity. At the heart of football’s great power of seduction is that there are certain sensations that are eternal. What a fan feels today thinking about the game is at the heart of what fans felt fifty or eighty years ago. Similarly, what Ronaldo thinks when he receives the ball is the same as what Pelé thought which in turn is the same as what Di Stefano thought. In that sense, not much has changed, the attraction is the same.’

As Gabriele Marcotti pointed out in an article in

The Times

, for Valdano that attraction is rooted in emotion. ‘People often say results are paramount, that, ten years down the line, the only thing which will be remembered is the score, but that’s not true,’ Valdano said. ‘What remains in people’s memories is the search for greatness and the feelings that engenders. We remember Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan side more than we remember Fabio Capello’s AC Milan side, even though Capello’s Milan was more successful and more recent. Equally, the Dutch Total Football teams of the 1970s are legendary, far more than West Germany, who beat them in the World Cup final in 1974, or Argentina, who defeated them in the 1978 final. It’s about the search for perfection. We know it doesn’t exist, but it’s our obligation towards football and, maybe, towards humanity to strive towards it. That’s what we remember. That’s what’s special.’

Even as Sacchi entered his thirties, though, his quest for perfection was in its infancy. From Baracco Luco, he moved on to Bellaria before, in 1979, joining Cesena, then in Serie B, where he worked with the youth team. That was a Rubicon. ‘I was still working for my father’s business, so that was a real lifestyle choice,’ Sacchi said. ‘I was paid £5,000 a year, which is roughly what I made in a month working as a director for my father’s company. But in a way that freed me. I never did the job for money because thankfully I never had to think about it.’ It was a gamble that was to bring an almost unthinkably rapid return.

After Cesena, Sacchi took over at Rimini in Serie C1, almost leading them to the title. Then he got his great breakthrough as he was taken on by Fiorentina, a Serie A club at last, where Italo Allodi, once the shadowy club secretary of Inter and Juventus, gave him the role of youth coach. His achievements there got him the manager’s job at Parma, then in Serie C1. He won promotion in a first season in which they conceded just fourteen goals in thirty-four matches - his attacking principles were always predicated on a sound defence - and the following year took them to within three points of promotion to Serie A. More importantly for Sacchi, though, Parma beat Milan 1-0 in the group phase of the Coppa Italia, and then beat them again, 1-0 on aggregate, when they were paired in the first knockout round. They may have gone out to Atalanta in the quarter-final, and they may not have won a single game away from home in the league that season, but Silvio Berlusconi, who had bought Milan earlier in the year, was impressed by what he had seen. He, too, had dreams of greatness and seems to have bought into Sacchi’s idealism. ‘A manager,’ Sacchi said, ‘can only make a difference if he has a club that backs him, that is patient, that gives confidence to the players and that is willing to commit long-term. And, in my case, that doesn’t just want to win, but wants to win convincingly. And then you need the players with that mentality. Early on at Milan I was helped greatly by Ruud Gullit, because he had that mentality.’

Still, the problem of credibility remained. Sacchi admitted he could barely believe he was there, but responded tartly to those who suggested somebody who had never been a professional footballer - Berlusconi, who had played amateur football to a reasonable level, was probably a better player - could never succeed as a coach. ‘A jockey,’ he said, ‘doesn’t have to have been born a horse.’

Sacchi addressed the issue straightaway, reputedly saying to his squad at their first training session, ‘I may come from Fusignano, but what have you won?’ The side may have been expensively assembled, but the answer was not a lot. Milan had lifted the

scudetto

just once in the previous twenty years, and were still struggling to re-establish themselves after their relegation to Serie B in 1980 as part of the Totonero match-fixing scandal. The previous season they had finished fifth, pipping Sampdoria to the last qualification slot for the Uefa Cup only in a play-off.

Sacchi’s resources were bolstered by the arrival of Gullit from PSV Eindhoven and Marco van Basten from Ajax for a combined fee of around £7million, but still there was no great expectation, particularly as Van Basten suffered a series of injuries, required surgery and ended up playing just eleven league games, most of them towards the end of the season. They lost their second game of the campaign, 2-0 at home to Fiorentina, but that was one of only two defeats they suffered that season as they won the

scudetto

by three points.

That summer, Frank Rijkaard became the third Dutchman at the club. He had walked out on Ajax the previous season, having fallen out with their head coach Johan Cruyff, and had joined Sporting in Lisbon. Signed too late to be eligible for them, though, he ended up being loaned out to Real Zaragoza; when Sacchi insisted on signing him, there was a distinct element of risk, particularly as Berlusconi was convinced that the best option was to attempt to resurrect the career of the Argentina striker Claudio Borghi, who was already on the club’s books, but had been loaned out to Como. Sacchi was vindicated, emphatically so, as Rijkaard’s intelligence and physical robustness helped Milan to their first European Cup in twenty years.

‘The key to everything was the short team,’ Sacchi explained, by which he meant that he had his team squeeze the space between defensive line and forward line. Their use of an aggressive offside trap meant it was hard for teams to play the ball behind them, while teams looking to play through them had to break down three barriers in quick succession. ‘This allowed us to not expend too much energy, to get to the ball first, to not get tired. I used to tell my players that, if we played with twenty-five metres from the last defender to the centre-forward, given our ability, nobody could beat us. And thus, the team had to move as a unit up and down the pitch, and also from left to right.’