Insectopedia (40 page)

As might be expected, there soon appeared a black market in crickets, fueled by parents determined that their children would experience the pleasures of selecting a fanciful cage and its tiny occupant, carrying home their new chirping friend, releasing it in their backyard, and if they were lucky, feeling its companionship as it sang for them throughout the summer. These were deeply felt pleasures of which people were reluctant to let go. But those deputies who supported the change didn’t simply reject such tradition; they saw themselves as embracing a dynamic conception of its possibilities, a conception in which intimacies with these animals were anachronistic, archaic. Somehow, in this official pro-cricket vision, the crickets themselves, the crickets as living beings, were so incidental to the

festa del grillo

that there was no question that it would persist without them, as a celebration of their absence and as a celebration of the enlightened thinking which made that absence possible. “Freeing the crickets we leave behind an aspect of the past that doesn’t reflect modern sensibility, without subtracting anything from the flavor of the event at the Cascine,” Vincenzo Bugliani of the local Green Party, the deputy with responsibility for the environment, told the national press. “The tradition,” he asserted, “evolves and improves.”

18

“The

animalisti

,” shouted a headline in

La Repubblica

, “have won.”

The new

festa

made its debut on Ascension Sunday 2001, along with a high-profile public-education campaign encouraging students to understand, honor, and respect the

grilli.

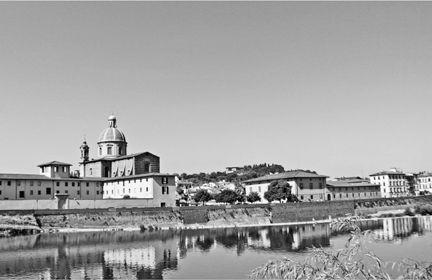

Exactly five years later, full of anticipation, we left our

pensione

, crossed the Ponte Vecchio, and walked out eagerly along the bank of the Arno to the Parco delle Cascine and the

festa del grillo

, excited to know what kind of event it had become. A cricket festival without crickets. The river gleamed, placid as a pond under the bluest Tuscan sky.

It was hot and humid. The air was thick and still. We’d been wandering around the park for hours. There was not a cricket in sight or earshot. Terra-cotta, mechanical, or even alive. And there weren’t any of Dorothy Spicer’s painted cages either. Were we in the right place? Had we got the date right?

As promised, there were plenty of vendors. They just weren’t selling crickets. There were toys, food, clothes, belts, caps, housewares. There were plenty of fake designer watches but not even one fake cricket. There were two long lines of stalls, tightly packed along the park’s main thoroughfare. Right in the middle, attracting the biggest crowd of all, was a large stand with sad-looking caged animals, dogs, cats, exotic birds—none wild, autochthonous, or illegal.

We walked up and down the strip yet again, then cut out to cover the park more systematically in case the cricket action was elsewhere. We

stumbled upon the Fonte di Narciso, where Shelley (who elsewhere wrote of insects as his “kindred”) composed “Ode to the West Wind,” and we puzzled over a mysterious overgrown pyramid, which, we later found out, was one of the Cascine’s famous icehouses. We found the amusement park and the handsome eighteenth-century façade of the School of Agricultural Science, in which Italo Calvino studied briefly before joining the partisans. And we saw the “no thoroughfare” signs beside the market that read “Divieto di Transito per Festa del Grillo,” the sole indication that this was the event for which we’d come all the way to Florence.

But it must be somewhere, surely. We must be somehow missing it, surely. And simultaneously, we both remembered a hazy afternoon more than twenty years before when we’d stood on the terrace in front of Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre, looking out over the soothing gray panorama of Paris and trying without success, for a full ten minutes, to locate the Eiffel Tower until, all of a sudden, as if clouds had cleared, the city’s most prominent structure suddenly appeared soaring high above the landscape in the very center of our view and we couldn’t imagine how we’d failed to see it. And as that memory surfaced, we discovered that the man who runs the immaculate public restrooms in the middle of the Cascine was Brazilian, from Fortaleza, in Ceará; that he was a great conversationalist; that he was delighted to talk in Portuguese; that he had arrived in Florence thirty years ago after passing through Paris; and that, unlike the Eiffel Tower two decades earlier, the

festa del grillo

would not be appearing miraculously from the ether that afternoon.

So here was Seu Edinaldo from Fortaleza, full of life and energy, with just a touch of the melancholy of exile. I don’t know if he and his wife lived in the building, but they’d turned it into a tropical home, the most beautiful restrooms you can imagine, magical restrooms, all beaded curtains, whitewashed walls, cutout magazine photos of birds and landscapes, floors so burnished you could take your reflection as a dance partner. Seu Edinaldo’s family is in Rio and São Paulo, but it’s too late to go back. Oh, the

saudades

, the longing, the absence.

The crickets? A few years ago they changed the law and banned the sale of live crickets at the

festa

, he said. And since then, well, it’s not really the

festa del grillo

anymore. It used to be such a special day; at one time

tens of thousands of people came out for it, grown-ups, children—it filled the park. Now … he gestured toward the market and the sparsely occupied lawns. On the other hand, he continued, seeing our disappointment, if you’re lucky, if you search carefully in the stalls, you might find one of the little battery-operated insects they’ve been selling for the last few years. And maybe you’ll find one of the cages, though it’s been a while since I’ve seen one, he added.

So we did look again, and this time we saw a T-shirt with a bee on it, and some painted clay ladybugs, and a diamanté (or maybe cubic zirconia) butterfly pin, and some plastic Chinese singing birds in green and gold cages that just for a second we thought held crickets, and one table with some very blond dolls and a few Tamagotchi, the lovable-egg virtual pets that were such a phenomenon in Japan in the late 1990s and which in that moment, on that table, made perfect sense as reincarnations of the

grillo parlante

, returned from the dead, just as he returns, without explanation, at the end of Collodi’s masterpiece.

Why so perfect? Because through the Tamagotchi—its fans claimed—young people could learn to care for other creatures, could grow to appreciate the needs of beings apart from themselves, could acquire an early intimacy with mortality and the uncertainties of life, could gain a practical knowledge of the connectedness, the pleasures, and the sadnesses of life. And it seemed serendipitous to see them here at the new

festa del grillo

because these claims for the Tamagotchi are exactly the same as the claims for crickets advanced by their admirers, that is, by those cricket lovers who love being around crickets, who love having a cricket as a personal friend to talk to, to listen to, to play with, to feed, and to share their house with for the summer of its life. These are the claims they used against those other lovers of crickets who are so determined to save crickets from that kind of possessive love and the confinement and loss of freedom that is its gift, who see themselves as the selfless lovers, the pure lovers, the lovers who can love without demanding anything in return, whose theme song might well be Sting’s “If You Love Somebody Set Them Free.”

But that battle was over, at least for now. There were no more crickets in the Parco delle Cascine on Ascension Sunday, and there were no more cricket intimacies to serve as the stuff of moral education and future nostalgias. There were only the Tamagotchi. And no one seemed to be buying them anyway.

Q

uality of Queerness Is Not Strange Enough

1.

Have a look at this photograph. It was taken in Rondônia in the southwest Brazilian Amazon on March 15, 1991, by George O. Krizek, a psychiatrist and amateur entomologist from Florida. On the left is a butterfly of the genus

Dynamine;

on the right, a rove beetle.

1

Dr. Krizek was observing the beetle when the butterfly showed up. He or she (the article doesn’t specify) landed on the left-hand leaf, extended its proboscis, and right away began exploring the beetle’s raised anus.

Krizek whipped out his camera. But by the time he’d adjusted the focus, the sheepish-looking butterfly—maybe not wanting to be caught

at such an intimate moment—had withdrawn. Still, it’s not hard to imagine what this picture would have looked like had the doctor moved a bit faster.

Who knows what Dr. Krizek witnessed that day in Rondônia? Let’s suppose it really was some casual interspecies ass play (I’m sorry, I can’t think of a more polite term). And let’s suppose, as Krizek suggests, that the two animals had no ulterior motives: the beetle wasn’t a mantis trying to lure the butterfly for a next meal; the butterfly wasn’t an ant tailing an aphid for sugary anal exudates. Let’s suppose, instead—as Dr. Krizek supposes—that these were just two little animals enjoying a little action, getting to know each other, and feeling pretty good about it.

Krizek had no doubt about what he saw. Both insects were “calm” throughout their six or seven seconds of intimacy. (Calmer than he was, in fact.) All signs were that their interaction was consensual. If this cross-species “orogenital contact” had occurred between a human and another mammal, he said—and as a practitioner in the field, he spoke with some authority—it would have been instantly recognized as a “sexual paraphilia,” that is, a fetish.

But, Krizek adds, international psychiatric terminology is restricted to humans, so this interaction needs another name. He suggests

zoophilia.

He must know that this is the current term for the activities of people who enjoy sex with animals of other species, the term that even the animal lovers themselves now use for what was once bestiality. Could his just-too-late photo be an open invitation to sexual explorers of all species to launch their brave new world of truly diverse diversity?