Insectopedia (60 page)

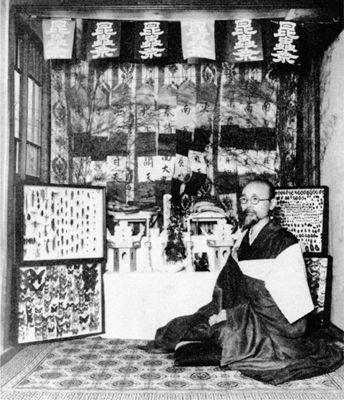

Shiga Usuke also experienced this unease. One year, on the anniversary of the opening of his store, he invited a Buddhist priest to come to Tokyo from the mountains and perform

kuyou

to console the souls of the departed. Instead of photos of the dead, he arranged specimens. Instead of favorite human foods, he arranged insect food. This was more than seventy years ago, in the 1930s. The sense of guilt about other beings, he writes, the sensibility that killing living things is wrong, is far from new.

He tries not to care about this, but he can’t escape it. He often wonders which is better: to live as a mayfly for only one day or to survive as a specimen for hundreds of years.

I’m happy that I’ve known insects, says Yajima Minoru. Shiga Usuke feels the same way and adds that it’s easy to get to know them. All you need is a magnifying glass and a net (maybe one of his inexpensive folding pocket nets).

As you observe tiny insects, writes Shiga-san, you’ll grow more interested in nature and you’ll find more pleasure and more satisfaction in the world around you. There is really nothing better than getting to know insects. The relationship between human beings and nature starts with insects and ends with insects, he says. And then he adds: my life has been exactly like that.

en and the Art of Zzz’s

1.

In 1998, I was lucky enough to get a job teaching at the University of California in Santa Cruz, a beach town in northern California. I hadn’t expected the offer and it came as a surprise. Both Sharon and I were raised in cities, and apart from my extended stay in Amazonia, neither of us had spent much time anywhere smaller. We were happy in our barely heated apartment in downtown Manhattan, even though the cold from the refrigerated warehouse below would often eat right through the floorboards and into our bones. But California seemed like an adventure, a whole new world. We packed up our stuff, rented a car, and set off like a couple of pioneers, trying to imagine what we’d find on the far side of the Holland Tunnel.

Our favorite beach in Santa Cruz was at Wilder Ranch State Park. It’s called Three Mile Beach. To get there, we would walk along the cliff tops overlooking the Pacific at the northern tip of Monterey Bay. Because it’s so exposed, Wilder Ranch is usually windy and often much colder than Santa Cruz itself, which, only two or three miles away but sheltered by the bay, is a miracle of balmy weather.

The walk along the cliffs is blustery but astonishingly beautiful. We couldn’t tire of it. The ocean, like all large bodies of water, never looks the same from one day to the next, and its mood always caught us unawares. Feet planted firmly on the cliff edge, high above the waves, we would

look out on sea otters, seals, and sea lions far below. Sharon was the champion at spotting whales, and she’d point out gray whales and humpbacks spouting, sometimes pretty close to shore. We would tip back our necks, back, back, back into the sharp glare of the sun just as flocks of pelicans—the most inspiring of all—soared overhead, the whitest white against the bluest sky.

Once we came across a dead whale. For days, we’d smelled the stench of something rotting as we drove out past the flat fields of artichokes that line the ocean side of Highway 1, a stench so strong that despite the summer heat, we rolled up the windows on our un-air-conditioned Datsun pickup and kept them up for miles. The next time we went to Wilder Ranch, we realized that the source was nearby. As we walked out along the cliffs, the smell grew more intense until the path fell away above a narrow inlet, and below we saw a discolored hulk, something indefinite that slowly became a whale.

The animal was melting, dissolving into viscous liquid. Its mouth gaped open. Its massive penis dug awkwardly into the sand. Everything

was awkward. Everything about it was wrong. Its skin peeled away in slimy blues and greens. All around it buzzed clouds of flies.

When the weather was warm enough and the wind not whipping up the sand, we’d sit and read on Three Mile Beach. It was usually deserted, and sometimes I’d strip off and swim out a short distance, cautious of the crosscurrents and riptide, the icy water shocking my warm skin.

The beach is a pocket, a cove between the cliffs that slopes down gently into the ocean on one side and gives out into wetlands on the other. It has fine pale-golden sand and dotted clumps of tough marsh grass. We’d spend hours there, stretch out, breathe the sun into our bodies, the open sky above us, around us the roar of the surf as it rushed in, the tumble of smooth rocks as it poured out again.

But despite all this, it was often hard to relax on Three Mile Beach. There were tiny flies, maybe the same flies that swarmed around the whale. They were fast and they were determined, too, impossible to deter. Every few seconds, one would deliver a sharp pinprick to an exposed leg or arm and then zoom off. The pinpricks hurt. They didn’t leave a mark, not even any redness, but they made it difficult to sit still and even harder to sleep.

Recent research suggests that insects sleep. Or at least like most other creatures, they go through regular periods of rest and inactivity, during which their responses to external stimuli are greatly reduced.

1

It would have been helpful if we’d known how to coordinate our visits to the beach with the flies’ inactivity, but that just wasn’t possible.

The sleep research doesn’t investigate whether insects dream. That’s

a little too speculative for biologists right now. Perhaps the methodology isn’t obvious. But what if they do … What do they dream of? Yet more unanswerable questions.

The insects are all around me now. They know we’re at the end. They’re saying, “Don’t leave us out! Don’t forget about us!” I’m trying hard to include them all. But, honestly, there are just too many. Even the most ambitious and richly illustrated insectopedia wouldn’t have room. Even Vincent Resh and Ring Cardé’s monumental

Encyclopedia of Insects

had to perform some triage.

The beach flies stopped us from sleeping. Their bites were sharp stabs. They refused to leave us alone. In other ways, they were very Californian. They kept repeating the same thing, a four-part mantra: This is our beach too. Learn to live with imperfection. We’re all in this together. The minuscule, a narrow gate, opens up an entire world.

Air

1.

P. A. Glick,

The Distribution of Insects, Spiders, and Mites in the Air

, U.S. Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin 671 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1939), 146.

2.

For these and other examples of airborne dispersal, see C. G. Johnson,

Migration and Dispersal of Insects by Flight

(London: Methuen, 1969), 294–96, 358–59. I have drawn heavily on Johnson’s classic book and on Robert Dudley’s

The Biomechanics of Insect Flight: Form, Function, Evolution

(Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000) for this chapter.

3.

B. R. Coad, “Insects Captured by Airplane Are Found at Surprising Heights,” in

Yearbook of Agriculture

, 1931 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1931), 322.

4.

Glick,

Distribution of Insects

, 87. On ballooning, see Robert B. Suter, “An Aerial Lottery: The Physics of Ballooning in a Chaotic Atmosphere,”

Journal of Arachnology

27 (1999): 281–93.

5.

Johnson,

Migration and Dispersal

, 297.

6.

See, for instance, A. C. Hardy and P. S. Milne, “Studies in the Distribution of Insects by Aerial Currents: Experiments in Aerial Tow-Netting from Kites,”

Journal of Animal Ecology

7 (1938): 199–229.

7.

William Beebe, “Insect Migration at Rancho Grande in North-Central Venezuela: General Account,”

Zoologica

34, no. 12 (1949): 107–10.

8.

Dudley,

Biomechanics of Insect Flight

, 8–14, 302–9.

9.

L. R. Taylor, “Aphid Dispersal and Diurnal Periodicity,”

Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London

169 (1958): 67–73.

10.

Dudley,

Biomechanics of Insect Flight

, 325–6.

11.

Johnson,

Migration and Dispersal

, 606.

12.

Ibid., 294, 360.

Chernobyl

1.

In English, these insects, classified as a suborder of the Hemiptera, are known as the true bugs.

2.

Cornelia Hesse-Honegger,

Heteroptera: The Beautiful and the Other, or Images of a Mutating World

, trans. Christine Luisi (New York: Scalo, 2001), 90.

3.

Hesse-Honegger reflects on her career in a number of short published articles and, more extensively, in two books:

Heteroptera

and

Warum bin ich in Österfärnebo? Bin auch in Leibstadt, Beznau, Gösgen, Creys-Malville, Sellafield gewesen …

[

Why Am I in Österfärnebo? I Have Also Been to Leibstadt, Beznau, Gösgen, Creys-Malville, Sellafield …

] (Basel, Switzerland: Éditions Heuwinkel, 1989). A short article that includes four good-quality color reproductions can be found in

Grand Street

70 (Spring 2002): 196–201. Two beautifully produced exhibition catalogs also contain autobiographical accounts and useful critical essays: Hesse-Honegger,

After Chernobyl

(Bern, Switzerland: Bundesamt für Kultur/Verlag Lars Müller, 1992), and Hesse-Honegger,

The Future’s Mirror

, trans. Christine Luisi-Abbot (Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K.: Locus+, 2000). My thanks to Steve Connell for all translations from the German.

4.

Hesse-Honegger,

Heteroptera

, 24.

5.

Hesse-Honegger,

After Chernobyl

, 59.

6.

Hesse-Honegger,

Heteroptera

, 9.

7.

Galileo Galilei,

Sidereus nuncius, or The Sidereal Messenger

, trans. Albert Van Helden (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 42, quoted in Hesse-Honegger,

Heteroptera

, 8.

8.

Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, “Wenn Fliegen und Wanzen anders aussehen als sie solten” [When Flies and Bugs Don’t Look the Way They Should],

Tages-Anzeiger Magazin

, January 1988, 20–25.