Insectopedia (36 page)

She turns back to catching insects under the shadeless sun. The rest of us follow suit and are soon scrambling around chasing

houara

in the dust. And what I remember best about this is that Boubé was really good at it, that he kept going long after Karim and I had given up, that he really didn’t want to leave, and that in no time at all the rest of us were standing out there under that everlasting blue sky watching him digging in the bushes and laughing at his success.

A few days later, there were again four of us passing through the police roadblocks and bouncing along the red road north from Maradi. This time, Hamissou was busy elsewhere, and we were accompanied by Zabeirou, an energetic presence in the front seat next to Boubé, explaining

in a stream of Hausa, French, and English how he had become the largest

criquet

merchant in Maradi, if not in the entire country.

From 1968 to 1974, a savage drought and famine, compounded by outbreaks of

Schistocerca gregaria

, destroyed Niger’s groundnut economy. Hunger forced farmers to abandon export cropping and return land to subsistence foods, the displacement of which had so undermined their security. Across the Sahel, between 50,000 and 100,000 people died. In Niger, groundnut production plummeted from 210,541 tons in 1966 to 16,535 tons in 1975.

21

But by the mid-1970s, some of the world’s largest deposits of uranium, discovered by the French atomic energy commission in the Aïr region, were filling the fiscal void. At its height, uranium provided well over 80 percent of the country’s export revenues and stimulated a national economic boom. But by the early 1980s, following the meltdown at Three Mile Island and the success of the anti-nuclear movement in Europe and the United States, the price of uranium began its long fall, a slump from which it is only now emerging.

22

Production of uranium in Niger collapsed along with the price, once more throwing the economy into a revenue crisis and even further on the mercies of the multilateral donor agencies and their punishing financial prescriptions.

At the beginning of this cycle, the uranium enterprise SOMAIR—a subsidiary of the French nuclear conglomerate COGEMA—built a new mining town out in the desert 150 miles north of Agadez. This was Arlit, called Petit Paris for its expat-focused amenities, such as supermarkets stocked directly from France. It was here that Zabeirou had worked as a laborer until 1990, when he left with a payment of 150,000 CFA (something like $550 in those days). He moved back to Maradi and, once there, started to study the markets. He quickly saw that there was a high demand from women for

criquets

and that—unlike other popular goods—there were no big operators working the trade. The

alhazai

of Maradi had failed to step in, and business was dominated by petty entrepreneurs.

As he tells it, Zabeirou moved decisively to become Niger’s first serious

criquet

merchant. Armed with his Arlit capital, he built up his stock by buying all the animals he could from rural collectors. Once he’d cornered the market, he slashed his price deep enough to force out the competition. With his monopoly in place, he raised his prices again and soon recovered his losses.

Nowadays, the competition is more serious and Zabeirou’s business more elaborate. He has a network of informants scattered in towns and villages around Niamey, Tahoua, and Maradi and across the border in northern Nigeria whose job is to seek out

houara

in times of scarcity. He also has buyers, each with a budget of 300,000 CFA, whom he sends out from Maradi and Niamey to procure in villages and markets. It’s a wary world. Zabeirou keeps his sources secret. Often, he keeps his own location hidden too, moving around clandestinely, letting people think he’s in Maradi checking on supply when he’s actually doing business in Niamey. It’s a wary world, but it pays off: there have been times when he has made 1 million CFA in a week.

When he is in Maradi, Zabeirou is most likely to be at Kasuwa Mata, the Women’s Market, a mostly wholesale market on the northern edge of the city dominated by women traders. Kasuwa Mata is a staging area for goods arrived from the countryside. From here, they go to the Grand Marché and other outlets in town, to markets elsewhere in Niger, and to buyers in Nigeria. Zabeirou has a well-stocked stall here, a destination for middlemen like Hamissou and for women collectors arriving from their villages with

houara

for sale.

He has four resale options: he can retail directly from his stall; he can

wholesale to traders in Kasuwa Mata and elsewhere in Maradi who then resell in the local markets; he can send sacks by truck for his employees to sell in Zinder, Tahoua, or Niamey; or he can take the

houara

to Nigeria. At this time of year, a time of high prices and scarce supply, many of his customers are women who prepare the animals for their preteen children to sell from metal trays balanced confidently on their heads. It’s a popular spicy snack, tiny packs of five or six insects for 25 CFA that other children buy outside their elementary schools or bigger packs for 50 CFA that the drivers of

kabu-kabu

, motorbike taxis, stand crunching as they wait for their next fare.

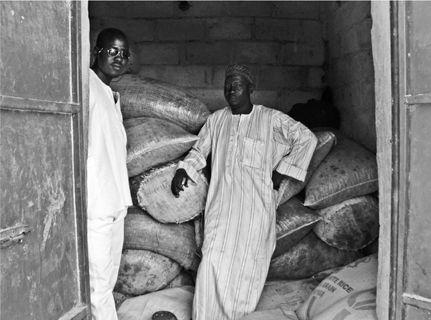

Zabeirou led us to a storage facility behind his stall and showed us some of his stock. Sacks and sacks of

criquets

, several months’ supply, 2 million CFA worth, he said. He would add to them over the next few weeks—until there were no more in the countryside and the price started to rise. Then he’d release them to the market. Good business, we all agreed.

Three wives and ten children. A large house with a walled yard close to Kasuwa Mata. Zabeirou’s prosperity was matched by his expansive manner. Karim and I were cautiously pleased that he’d decided to adopt

us. After a couple of hours on the road, we stopped in the market town of Sabon Machi, where he insisted on buying us a breakfast of

masa

and sweet tea. Another couple of hours and we arrived in the village of Dandasay.

Zabeirou’s brother Ibrahim is one of the three schoolteachers here. He has a quiet and gentle manner quite different from that of his older sibling. As we talk, I’m thinking what a sympathetic teacher he must be. He is telling me that parents in the village have so little cash that he is scared when he sometimes has to ask them for 10 CFA for supplies. He introduces me to his colleague Kommando, a strikingly tall, thin man with a similarly kind demeanor. Karim figures out that Zabeirou hasn’t been here before. Off-road on the last stretch of the journey to Dandasay, we’d been forced to stop for directions more than once. As we pulled into the village, he’d ordered the children who raced to greet us to run and tell their mothers that he’s here to buy

houara.

It turns out to be a complicated day. Assuming the twin roles of tour guide and impresario, Zabeirou has decided we need to see

houara

being prepared for sale. He begins to organize the performance but has barely started rounding up likely women when he discovers that the collectors have yet to come back from the bush and no one here has any fresh

criquets.

In the meantime, women alerted by their children have emerged from their houses with small bags of insects. Normally, they take these to the nearby market in Komaka or to Sabon Machi, bigger and further away, or, on a Friday, to Maradi, much bigger and further still. Normally, Zabeirou would have buyers waiting for him in those markets. But today is a special day, and he sets up shop behind our truck and starts to deal.

He hasn’t got very far when a group of men arrives to invite us to a

cebe

, a baby’s naming ceremony. It’s on the far side of the village, so Zabeirou suspends operations, and we make our way through the narrow sandy lanes to where the first row of chairs has been vacated in front of a thatched patio beside a small house. The imam takes his place on a mat among a group of senior men, and the audience watches, periodically joining in to recite the blessings, as the dignitaries move through the solemn ceremony. It’s calmly meditative, and everyone is focused on the chants with a quiet intensity. But as the service proceeds, I gradually become aware of what sounds like a spirited debate going on behind us.

I turn around, and there’s Zabeirou in position again at the back of the truck, bargaining with a line of women waiting to sell their

houara.

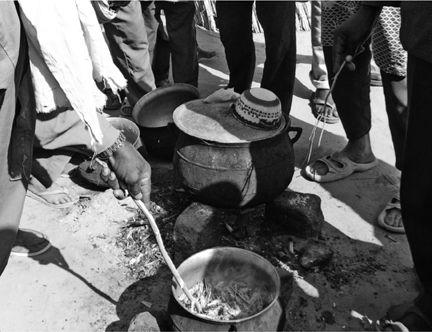

We’re treated too well here. After the ceremony, the father of the child invites us all to eat first, before his other guests. Karim, Boubé, Zabeirou, Ibrahim, and I enter a small round building and are served an elaborate meal of millet and meat. We reemerge to hear that the collectors have returned from the bush. A fire is hastily lit outside a nearby house, and a young woman (decidedly unimpressed) begins heating a large pot of water under the gaze of what is by now a sizable crowd. As the scene develops, Zabeirou offers detailed

National Geographic–

style commentary for our benefit and repeatedly cautions me not to miss the opportunity to take photos. When the

houara

arrive, he dumps them in the boiling water, takes the young woman’s stick, and not letting up his patter, shoves the flailing animals deep into the pot. The women who perform this mundane operation on a daily basis are shut out of the circle and wander off to more compelling things. The men take turns poking at the pot, closely watching something that they, too, must have seen untold times but takes me entirely by surprise: as they churn in the roiling water, the tan-colored insects rapidly turn pink, resembling nothing so

much as cooked shrimp and, in that moment, opening an unlucky door into other universes of possible fates.

The insects boil for thirty minutes. Meanwhile, Ibrahim and I chat with the

maigari

, the headman of this large village, and with a few other men. They tell us that the

criquet pèlerin

was here sixty years ago but has not been back since. These older men remember the destruction but—like the men in Rijio Oubandawaki—it’s not something they dwell on. Rather than this once-in-a-lifetime apocalypse, it’s the less exotic

houara

like the

birdé

, with their grinding away at everyday food security, that preoccupy them.

Kommando is part of this conversation, too. As it ends, he tells me that he used to work in a village about sixty miles north of here called Dan mata Sohoua. We should visit, he says. The chief there can tell us about the locust invasion of 2005. It’s quite a story. Just then I spot Zabeirou across the crowd. He has a

tia

and is using it to measure out the women’s insects. To the sellers’ dismay, he piles the animals high, mounding more and more until there must be as much as 40 percent extra heaped on the basin, which he then tips into his sack. As I watch, I recall how he always gives an additional “social payment” when he sells in Kasuwa Mata, how he piles on varying amounts depending on the status of the buyer (a widow, for instance, may get more), so that the

houara

spill over the lip of his

tia

in a gesture of generosity that is, however, somewhat more modest than the one he’s managing today.