Insectopedia (35 page)

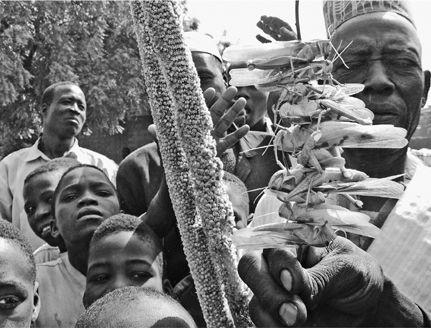

Fifteen years ago, the questioner explained, a team of agricultural-extension workers had come to the village. They trained people to use pesticides and left a supply for the residents’ use. Everyone applied the chemicals as instructed and was happy to see that they worked: insect

damage was significantly reduced, yields increased, and there seemed to be no harmful effects on crops, people, or other animals. Soon, though, the chemicals ran out, and fifteen years later the stock has still not been replenished. Nowadays, he continued as we all listened attentively, the only people who use pesticides in this village are the rich farmers, those with more than twenty-five acres, who can afford to buy chemicals privately. The

houara

avoid their fields and concentrate their appetites on the rich men’s less fortunate neighbors. Every year the insects and birds (those terrible birds!) eat our millet, our sorghum, and our cowpeas; sometimes they eat half our crop or more. We stretch wire for the birds, and we set fire to the

houara.

We burn the birds, too. But none of it helps. He lapsed into quiet and another man in the group spoke. Actually, he said, you

should

go to the ministry. When you do, if you look hard enough, you’ll find thick folders of paperwork about this village. You should go, but you shouldn’t bother talking to anyone about us. You shouldn’t imagine they’re not aware of the situation here. Whatever else is going on in the capital, it’s not ignorance.

The bus arrives and we clamber aboard. With the hugest red sun rising ahead of us, we’re soon barreling out of Niamey and across the baked landscape, its flatness punctuated by low rounded hills and sharp lateritic escarpments. For the next few hours, the two-lane highway is lined by ocher villages filled with family compounds of rectangular mud-brick houses. Graceful onion-shaped granaries overflow with sheaves of millet from the recent harvest. People sit outside their homes or at stalls along the road. Men build and renovate walls and fences, repair the granaries, hoe fields. Women thresh tall heaps of grain, pound millet for porridge, gather around village wells, carry large bundles of firewood or millet stalks, their dazzling cotton cloths billowing as they walk. Children collect wood too, or tend other children or herds of goats. We stop briefly to buy food in the crowded bus station at Birni N’Konni and then continue east, ignoring the turning that cuts north to Tahoua, Agadez, and the uranium town of Arlit. From this point on, everything feels a little

greener, a bit more prosperous: large herds of long-horned cattle, flocks of camels, their front legs loosely bound to stop them from straying too far too fast, droves of donkeys, more granaries, more fields, and the startling dark splash of irrigated onion patches.

Maradi hums with commercial energy, but its position at the hub of Niger’s economic life dates only from the end of the Second World War. Because of its geographic location and an inability to secure its supply lines, the town was excluded from the great trans-Saharan caravan routes that for centuries linked Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and other Mediterranean ports first to Zinder, Kano, and destinations close to Lake Chad, and then to the rest of Africa. This trans-Saharan trade supplied the eighteenth-century Hausa city-states, commercial powerhouses that in turn supplied gold, ivory, ostrich plumes, leather, henna, gum arabic, and, most lucratively, sub-Saharan slaves to Tuareg and Arab traders, who carried them north, returning from the coast with firearms, sabers, blue and white cotton cloth, blankets, salt, dates, and the multi-purpose mineral natron, as well as candles, paper, coins, and other European and Maghrebi manufactured goods.

17

By 1914, the British rail network through Nigeria had reached Kano, close to the border with Niger. It was now both cheaper and safer to send goods by train to Lagos and the other Atlantic ports than to ship them north on the cross-desert camel trains. Taking advantage of the decline of the caravans and the sudden access to transportation, the French administration pushed aggressively to provide the Maradi Valley with the initial capital and infrastructure needed to cultivate groundnuts for the colonial oil market. By the mid-1950s, Maradi was competing as a regional center for a crop that had been strongly commercialized by the French in Senegal and elsewhere in their West African colonies but until then had barely taken hold in Niger. Forced to pay colonial taxes in cash—and drawn to the new European trading houses selling imported goods—Maradi’s farmers brought more and more land into groundnut cultivation and initiated two dynamics that would prove devastating during the extended drought and famine that lasted from 1968 to 1974: the undermining of already-fragile food security through the large-scale substitution of groundnuts for staple crops, especially millet, and the encroachment on and effective privatization of grazing areas used by

Tuaregs, Fulanis, and other pastoralists, who, pushed with their animals onto increasingly marginal lands, would make up the significant majority of famine victims.

18

The border that split Hausaland between French-ruled Niger and the British Protectorate of Northern Nigeria was fixed in a series of conventions agreed to by the two colonial powers between 1898 and 1910. Insecure about the transborder loyalty of their Hausa subjects, the French funneled their patronage to the Djerma of western Niger, moving the capital from Zinder to Niamey in 1926. “While roads, schools, and hospitals were gradually introduced [by the British] into Northern Nigeria,” writes the anthropologist Barbara Cooper, “the French permitted Maradi to languish as a neglected backwater in a peripheral colony, where infrastructure developed fitfully if at all.”

19

The effects of these policies were, predictably, not quite as intended. Even though precolonial Hausaland had been riven by violent rivalries, the common experience of colonial exaction under both British and French rule, plus the persistence of cultural, linguistic, and economic connections, created powerful cross-border identifications that continue to this day. One mark of this linkage is the emergence in Maradi of the

alhazai

(from the Islamic honorific Alhaji—he who has completed the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca), powerful Hausa merchants who began their careers in the groundnut industry and the European trading houses but rapidly diversified to exploit the opportunities for commerce, licit and illicit, offered by the border. As Cooper notes, it was the ability of the

alhazai

to capitalize on British investments in northern Nigeria—such as the rail link to Kano—that propelled them to prominence and allowed them to weather such crises as the famine of 1968–74 (from which many profited handsomely) and the devaluations of the Nigerian naira in the 1990s.

The

alhazai

are also lively participants in the global Islamic geography that links Maradi to Egypt, Morocco, and other sites of higher education, and to Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and other centers of big capital. And they are conspicuous in the resurgent Islamic networks that tie the city to the twelve sharia-governed states of northern Nigeria. Recalling his experience as a leftist student activist confronting the rise of a newly politicized Islam in the university, Karim predicts that the young urban intellectuals

leading the Islamist organizations will take power in Niger within twenty years. Their discipline, probity, and commitment has a powerful appeal, modeling a future radically distinct from the remoteness and opportunism—the lack of ideology, as Karim puts it—of the politicians in Niamey and the debilitating combination of ineffectuality and neocolonial authority that has come to characterize the aid organizations.

Discourses of political and moral decadence easily merge. The riots that shook Maradi in November 2000 were led by Islamist activists protesting the Festival international de la mode africaine, a fund-raising fashion show backed by the United Nations that drew leading designers from Africa and overseas. Demonstrators denounced single women as prostitutes, targeting them in the streets and in a refugee village to which many had fled from prior Islamist violence in Nigeria. Rioters torched brothels, bars, and betting kiosks. They invaded Christian and animist compounds.

20

People in Niamey point to signs of change in public culture: stores that just a couple of years ago stayed open during Muslim prayers now shutter; large numbers of women on the university campus now wear veils. Maradi is in the vanguard of this complex struggle among “reformist” and “traditional” Muslims, evangelical Christians, and secular Nigeriens. Karim tells me it’s a very different place from when he lived here in the 1990s. Even so, one evening we’re taken by surprise in the city’s giant open-air movie theater when our undubbed, unsubtitled Hindi-language Bollywood gangster film cuts without warning into cheap hillbilly porn that someone has spliced into the pirated DVD. A thick sexual silence descends on a theater that moments before had almost as much life in the all-male audience as it had on-screen. But the surreal effect soon wears thin, and we head off to our hotel on the back of zippy motorbike taxis under starry black skies. When we arrive, Karim tells me that (despite the theater) the Islamists are the future now. With international development and its version of modernity discredited, with the nation in tatters, with no alternatives in sight, time is on their side. When I reply that I didn’t come all this way to write a lament for Africa, he offers a quote he attributes to Lenin: The facts, he says, are unavoidable.

January is as slow a month for

criquets

here as in Niamey. Yet, passing through the fortresslike gate of the Grand Marché, we’re right away in conversation with a friendly young guy who sells some

houara

here but mostly exports to Nigeria. The Nigerians look for insects from Maradi because they know that farmers in this area don’t use pesticides, he tells us. We ask where he gets his animals and he calls to a man sitting chatting at the back of the stall. Hamissou is a supplier with whom the owner of this stall has a long-term contract. He shyly describes how he’s been traveling through the villages north of Maradi on his motorbike for ten years buying millet,

bissap

(hibiscus flowers), and

houara.

Two days later there are four of us: Karim, Hamissou, Boubé (who usually drives for Médecins Sans Frontières), and me. We’re heading fast but cautiously—because of land mines—out of Maradi along a red dirt road so straight it seems it will never end. Hamissou is next to me in the backseat, dressed all in white, his cotton scarf thrown across his face against the dust.

Visiting villages with Hamissou was a pleasure. Everyone was excited to see him. His arrival generated laughter and excitement. Men jumped up to playact wrestling with him. They affectionately made fun of his shyness. His trade was a happy, relaxed affair with no economy of distrust.

That morning he took us into the bush to meet women collectors. They’d left their village after the 6 a.m. prayers, and when we caught up with them four hours later, they were far from home. They showed us where they find the

houara

under low shrubs, how they poke at them with millet stalks, catch them in one hand with swift, sure movements, snap the back legs of the lively ones to stop them from jumping, and secure them in a cotton pouch. If this were September, they said, they’d be collecting pounds every day, making 2,000 or 3,000 CFA from Hamissou and still having a good quantity left to eat.

Houara

replace meat, they said, reminding me of the conversation in Mahaman and Antoinette’s yard in Niamey. They’re full of protein and—also like

meat—they’re not something you eat every day (or, if you want to avoid vomiting and diarrhea, too much of). They’re delicious fried with salt or ground up to make a sauce for millet. In September, there are so many out here in the fields that we bring the children with us to hunt. But now, in January, it’s too cold in the mornings for children, and there aren’t any insects anyway. Look at this sad collection: it takes two days to fill this pouch, and it sells for just 100 CFA. Even the higher price this time of year doesn’t compensate for the poor supply.

If the returns are so low, why spend all these hours in such backbreaking work? I asked, stupidly. An older woman responded, not troubling to hide her scorn: Because we’re hungry. Because we have no money. Because we have to buy food. Because we have to buy clothes. Because we have to stay alive. Because in one month we won’t have even these few insects. Because there’s nothing else we can do to make money at this time. Because it’s something, and doing something is better than sitting at home doing nothing.

She continued: Sometimes there are years when the

houara

don’t arrive at all. But when they do, they help us build capital. With the proceeds from collecting, we can buy cooking oil, plastic bags, and everything else we need to sell

masa

, deep-fried millet cakes. With the proceeds from that, we can save a little more, buy our children things they need, create a little security. There are years when so many

houara

come to the village, she added, that we can even buy a cow. But what we can’t do is store the surplus against the times of hunger. They keep—that’s not the problem—but we can’t do without the cash.