Insectopedia (21 page)

To establish his case, he turned to physical principles that owed much to Aristotle. The cosmos that held sway in Renaissance Europe was divided into two realms: above, filled with the perfect and incorruptible ether, which moved in perfect and uniform motion, were the celestial heavens; below, abutting the lunar sphere, lay the terrestrial realm, constant only in its flux, composed of fire, earth, air, and water, the four types of terrestrial matter. Of those four elements, it was fire, the outermost surface of the terrestrial region, that occupied the most elevated natural place. Unimpeded, fiery bodies would always rise naturally toward the celestial realm, and in this sense they were closest to perfection.

26

By attaching his insects to fire, Hoefnagel fused them to the most exceptional element, the element associated with generation and dematerialization, the most protean, the most dynamic, the most unfathomable, and in early-modern Europe, the most wondrous. And crucially, in contrast to the logic of the other volumes of

The Four Elements

, fire is not the medium in which the insects live. Instead, it represents the properties they embody.

27

Rather than insects, though, the opening folio of

Ignis

depicts a human couple. The strange man with the penetrating gaze, whose wife rests her hand on his shoulder in a protective gesture, is Pedro González, the first of Hoefnagel’s

animalia rationalia.

Encountered on Tenerife and brought back to France, where he received a humanist education at court, González, as Hoefnagel’s inscription relates (and there is other historical documentation, too), was a man of letters well known in European society. His dress and demeanor indicate considerable cultivation, but his congenital hirsutism, as well as that of his similarly somber children, depicted in the following folio, places him in a tradition of wildness, a wildness further suggested by the blasted landscape. The landscape accentuates the couple’s solitude, and the golden circle within which they, too, are enclosed seems an ironic comment on their civilized careers. Imprisoned as they are by physical accident and perverse celebrity, any doubt as to their aloneness is dispelled

by the verse from the book of Job beneath the portrait: “Man born of woman, living briefly, a life replete with many miseries.”

28

But what kind of man? González and his children—as well as the projected, though never painted, giant and dwarf of folio 3—are the

animalia rationalia

, the only humans (along with González’s wife) in the entire

Four Elements.

Hovering on the edge of humanity, they are more wondrous still for remaining within its fold, bringing together rationality (which defines the human) and animality (against which the human is defined), unsettling the very idea of natural order. Physically, they are instantly recognizable as members of the races of wild men and monsters that populate the outer shores of the Renaissance imagination, beasts rather than men, the opposites of men through which we come to understand what men really are. Culturally, though, there can be no question that González is human; indeed, as Hoefnagel’s inscription makes clear, that he is a humanist. And in this decisive sense, his outsideness poses a profound challenge to the very idea of a humanity defined by its capacity to reason, a challenge that echoes that posed in the same years by Montaigne in his essay “On Cannibals,” in which it is the encounter with native Brazilians at the French court that throws into question the superiority of European civility.

29

The exotic problem of the Gonzalez family was widely recognized at the time. Important portraits were commissioned. Prominent physicians were consulted. Aldrovandi himself examined the family and included images of them in his

Monstrorum historia.

30

But of all the commentaries, Hoefnagel’s goes furthest. If these are victims, their sad situation is an indictment of intolerance, and in being invited to see them in this way, we are also, as the art historian Lee Hendrix suggests, reminded of the intolerance sweeping Europe that made a victim and a refugee of Hoefnagel himself.

31

If these are victims, then, like the victims of religious persecution, they are radically misunderstood. And these victims—and perhaps all the victims—are unmistakably wondrous. Imbued with fire, they rise above their earthly condition to soar naturally toward the celestial sphere. It is a powerful image, and it has stayed with me since that day at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The strange man whose penetrating gaze is fixed unflinchingly on the viewer. The sad but self-possessed woman who looks neither at her husband nor at the artist

but instead stares with blank resignation into an undefined distance and who is perhaps the most haunting figure of all: the one who chooses to transgress and thereby elects to suffer, the one positioned to mediate between the fully human and the

animalia rationalia

, the one about whom nothing is written, the one whose name and biography don’t appear to have been recorded.

Why does Hoefnagel bring the González family together with the

insecta

in this novel order of nature? Or more precisely, why does he use these human prodigies to frame and preface his book of insects? The answer must lie in what these beings share: a wondrousness brutally misconceived as imperfection, a common existence at the margins of nature. If González stands on the borders of humanity, insects stand both at the edge of nature and on the lip of the visible. On the threshold of hidden truths, they point beyond themselves, portals to the deep unknown, taking us—in this age before the microscope—“on an optical voyage into uncharted terrain.”

32

It took me a while to recognize

Ignis

as a form of what Sir James Frazer, the encyclopedist of early anthropology, called homoeopathic magic, that form of sympathetic magic based on the law of similarity, in which like

begets like.

33

I already knew that the work of the early-modern natural philosopher was to use the

ars magica

to reach through that gap between the visible and the intuited universe.

34

So why was I so slow to see that

Ignis

and its insects were themselves magical objects?

Perhaps it was that none of Frazer’s innumerable examples—refracted as they are through the imperial prism of early-twentieth-century social science

35

—appeared to correspond. Hoefnagel didn’t seem much like the “Ojebway Indian” who works his evil with “a little wooden image of his enemy and runs a needle into its head or heart.” Nor did he remind me of the “Peruvian Indians [who] molded images of fat mixed with grain to imitate the persons whom they disliked or feared, and then burned the effigy on the road where the intended victim was to pass.”

36

Nor were Hoefnagel’s so precisely realized insects reminiscent of these fetishes of wood and fat whose morphological likeness to their victims seems in Frazer’s account to be casually and abstractly gestural, perhaps even irrelevant.

Although he has his doubts, Frazer allows that when intentionality is clearly evident, the term “mimetic magic” may be permissible. This should have alerted me, or at least would have if I hadn’t been thinking of imitation as ruled by tragedy, of mimicry as always haunted by the repetition of its failure to become its object. I could still think of Hoefnagel as some sort of (very-ahead-of-his-time) Surrealist and of his mimetic method as a tactic of disruption calculated to destabilize his viewer and produce the psychic conditions for revelation. But maybe there was more? Frazer’s phrase reminded me of how, in his strange essay “On the Mimetic Faculty,” Walter Benjamin argues that the aspiration is not in vain. In Benjamin’s understanding of mimesis, there is no limit to the identification with the object made possible by the copy. Instead, in the words of anthropologist Michael Taussig, under the right circumstances, the object “passes from being outside to becoming inside.… Imitation becomes immanence.”

37

As were the insects it revealed, so was

Ignis

itself a wonder, its revelatory images the fruit of Hoefnagel’s astonishing capacity to breathe life into his subjects. Even though, like most painters of the time, he based much of his work on other artists’ representations, his was a celebrated ability to move beyond simple copying. In his hands, even Dürer’s

famous stag beetle was re-inspired and in its new aliveness took the viewer that much closer, tantalizingly closer, to the promise of whatever lay beyond.

38

Try not to think of this copying as imitation. Think of it as philosophical art in the service of something greater and more mysterious. It expresses piety, of course—these are God’s creatures—but also the associated desire to reach deeper, to cross the gap between representation and the real, between vellum, paint, and insect, between subject and object, between human and divine, between human and animal. Rather than producing a likeness of a being to act upon that being—as in Frazer’s examples—Hoefnagel’s likenesses aim to bring us to a point of identity with the being depicted. This is imitation striving for immanence and doing so through empathy—an empathy generated through wonder and a wonder created by an array of destabilizing tactics (those tactics that let me imagine Hoefnagel as an early-modern Surrealist).

Central to it all is the work of active viewing which Hoefnagel demands. It is impossible to pass lightly over his insects. Just as Pedro González locks us in his stare, holds our attention, and insists that we acknowledge him as subject (as person, as citizen, as topic, and as victim), so the detailed precision of Hoefnagel’s insects draws us into their individuality and elicits the same type of concentrated focus on the being in itself as would a lens, pulling us into the mysterious vitality of animate nature.

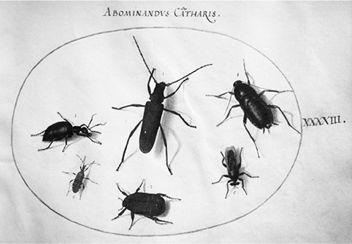

The dramatic staging heightens the effect: the background, usually blank, offers both depth and surface (note the delicate shadowing) yet removes the distraction of earthly context, leaving the insects in an independent, featureless space, a space I think of as ontological rather than—as we might expect today—ecological or historical. Abruptly, and this is part of what provokes that sudden gasp, Hoefnagel draws us into the tiny creatures’ scale. We become small, as if we have passed through his looking glass. Variations in the animals’ size—from the teeniest flies to the most monstrous spiders—are startling, frightening, but also exciting. He emphasizes their movement, their sense of purpose, intimating a motivating intelligence. Such wonders demand humility. They confront us with the limits of our understanding and with the poverty of the normality in which we dwell. This encounter wrought by mimetic magic takes us further and further into a secret realm. Deeper and deeper, closer and closer, up against the limits of communication, up against the ineffable.