Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (39 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Retail sales in the resurgent downtown have exploded since 1991. So has the taxable value of downtown properties, which cost a fraction to service than sprawl lands. The reborn downtown has become the greatest supplier of tax revenue and affordable housing in the county—partly because it relieves people of the burden of commuting, and partly because it mixes high-end lofts with modest apartments. All of this, while growing what one local newspaper emotionally described as, “a downtown that—after decades of doubt and neglect—is once again the heart and soul of Asheville.”

The Unequal Geography of Density

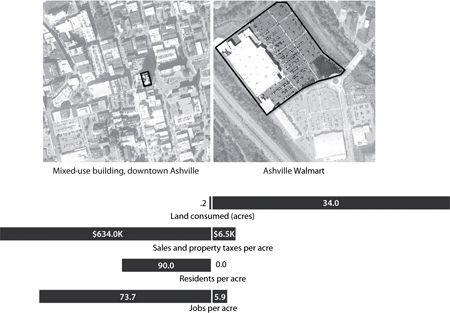

By investing in downtowns rather than dispersal, cities can boost jobs and local tax revenues while spending less on far-flung infrastructure and services. In Asheville, North Carolina, Public Interest Projects found that a six-story mixed-use building produced more than thirteen times the tax revenue and twelve times the jobs per acre of land than the Walmart on the edge of town. (Walmart retail tax based in national average for Walmart stores.)

(Scott Keck, with data from Joe Minicozzi / Public Interest Projects)

By paying attention to the relationship between land, distance, scale, and cash flow—in other words, by building more connected, complex places—the city regained its soul and its good health.

Growth Within Limits

By now you won’t be surprised to hear that what Joe Minicozzi and his friends are doing to improve downtown Asheville also happens to be a strategy for fighting climate change. In Asheville, everything is just as connected to everything else as it is in large cities. Efforts to create nodes of jobs density, residential density, and tax density also produce nodes of energy efficiency that lower the cost of running the city. “The low carbon community is also about ensuring that you can finance the sewage, the water, and roads to sustain your community on the long-term basis,” Alex Boston points out.

An average city can end up collectively spending more than $4,000 per household per year on energy, typically moving vehicles or heating and lighting buildings. Most of that money gets sucked right out of the community and paid to distant energy utilities or oil companies. How do you turn that around? By changing the city’s relationship with distance and with energy.

Few cities have done this as dramatically as Portland, Oregon. Back in the 1970s the state of Oregon ordered its cities to create urban growth boundaries in order to protect agricultural land. Then, while other cities kept pouring resources into freeways, Portland began investing in light-rail, streetcars, and bicycle lanes. Between 1990 and 2007, as people in most cities drove farther and farther every day, Portlanders were reversing the trend. Drivers now travel about 20 percent fewer miles every day than citizens of other major cities in the United States, shaving about nine minutes off the average daily commute. Traffic fatalities fell by 80 percent between 1985 and 2008, again bucking the national trend.

Aside from the millions saved in emergency and medical services, the trip shortening has had a salubrious effect on the local economy. Thanks to their shorter commutes, by 2008, people in the Portland region were saving about $1.1 billion every year on gas, or 1.5 percent of all personal income in the region. This means that Portlanders send less money out of the city to car companies and oil barons and spend more at home in their city on food, fun, and microbrewed beer.

*

The result: Portland has more restaurants per capita than any large city in the country other than Seattle and San Francisco. All this good living allowed Portlanders to spare the world about 1.4 million tons of greenhouse gas per year. It was a gift to their children and to their planet, but what got people really excited was that Portland’s climate-friendly systems attracted wealth. An investment of $100 million in slow-moving downtown streetcars actually pulled in $3.5 billion in new office, retail, and hotel development within a couple of blocks of the new lines.

Portland’s experience proves that a city can make massive carbon reductions without turning to hyperdensity, argues Boston. “Density alone doesn’t lead to carbon reductions, or happiness for that matter. You can live in a forest of apartment towers and still be forced to drive everywhere. But when cities find ways to mix housing and jobs and places to shop, then carbon goals and lifestyle goals start to converge.”

Boston has experienced these dividends firsthand. First he helped create a climate action plan for the City of North Vancouver, a mountainside suburb just across a broad saltwater harbor from Vancouver. His metrics were straightforward: if the city was going to reduce its carbon footprint, it needed to give lots more people a chance to do a lot more things closer together. This did not necessarily mean building a mini-Manhattan. It meant weaving more apartments, more town houses, more shops, and more jobs along Lonsdale Avenue, the city’s central spine. Indeed, that’s what the city was already doing in the name of prosperity. The area had attracted hundreds of new residents—including Boston and his partner, who moved there to start a family two years after he helped hammer out the city’s climate action plan. They bought a duplex beneath a huge cedar tree on a quiet street, just a couple of blocks off Lonsdale. They immediately started reaping the benefits of the climate-friendly system.

For one thing, it made them richer: Since 2005, the city’s efforts to build more efficient communities had cut per capita energy costs by about 10 percent—saving citizens each about $400 every year. Boston’s utilities bill (which covers water, sewage, garbage collection, and recycling) was about three-quarters what it would have been if he had moved to the similarly named but more sprawling District of North Vancouver, which bordered the city.

The changes also made Boston’s everyday life easier, healthier, and more convenient. This was apparent when I joined him on his daily commute to downtown Vancouver. The ritual included a twenty-minute walk and a fifteen-minute ride across the harbor on the SeaBus, a small passenger ferry. As we walked, he pushed his rosy-cheeked year-and-a-half-old son, Kenson, along in a stroller.

The most remarkable thing about the trip was not the ease of the transition from quiet backstreet to busy Lonsdale. Nor was it the wonderful urban collage Boston noted as we walked—from typical main street businesses to light industrial shops, including a metalworks, an auto body repair garage, and a cabinetmaker—land uses that meant people could live, shop, and work steps from home. What impressed me most was the detour Boston took just before getting on the SeaBus.

We headed past the market at the foot of Lonsdale and past the office block that sat above the bus exchange, and Kenson grew increasingly excited. As we approached a spiffy-looking mid-rise condominium tower, he broke into a wide-mouthed grin. He pointed and cawed as a white-haired gentleman emerged from the lobby. His babysitter for the day was Boston’s own father. The climate technician had convinced his aging parents to trade their home in sprawl for a condominium in North Vancouver’s low-carbon complexity.

“So you moved for the sake of the climate?” I prompted Boston senior.

“Well, it rains here just as much as it did at our old house,” he replied.

“No, Dad, he’s talking about climate change. About greenhouse gas emissions,” Boston junior interrupted.

Boston senior gave me a wink. He didn’t seem to give a damn about the city’s carbon credentials, but he loved its sheer handiness. They walked to pretty much everything they needed. The price? More babysitting—a dividend for Alex that would have been much more difficult to collect in the dispersed city.

The Boston family is not alone in appreciating the city’s low-carbon payoff. During the years that the City of North Vancouver was making its carbon U-turn, pollsters found that citizens were getting happier and happier with their quality of life.

Body Heat

Sometimes the dividends of proximity and complexity are invisible, intangible among the myriad relationships, geometries, and systems of the city. But sometimes they are clearer than even Bjarke Ingels’s architectural metaphors, and they reveal new truths about the interconnectedness of city systems.

In its role as host city for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games, Vancouver built a village for athletes on the southeast shore of False Creek, a former industrial waterway on the edge of its downtown. The Village, as the area is now known, is a showcase of green urbanism, from its rainwater-fed mini-wetland to its LED-lit central plaza. Eventually sixteen thousand people will live in the low-rises and town houses that line its narrow pedestrian-friendly streets. The last time I strolled through—about three years after the Olympics—residents had colonized the new bakery-café, children were clambering over the feet of the giant sculpted fiberglass starlings that rule the plaza, and the seawall hummed with skaters, stroller-pushing joggers, and bike commuters. Outside the new community center, teams of Lycra-clad paddlers stretched and chatted, preparing to launch their dragon boats off a nearby dock into False Creek.

The social energy converging on the Village is impressive. But this energy convergence goes beyond metaphor: all those human bodies are vessels of

thermal

energy. As human density increases at the Village, so does the density of energy its residents cycle through the air and water systems of their buildings, through their machines, and through their own bodies, concentrating a resource that has now been harnessed by a remarkable new power system. This is how the Southeast False Creek Neighbourhood Utility works: Every time residents of the Village do their dishes or take a shower or use the toilet, they flush thermal energy—either in the form of room-temperature water or considerably warmer human waste—down the drain. The wastewater gets piped to a sewage pumping station submerged under a nearby bridge. Inside that station is a small energy plant that uses a process of evaporation and compression to suck the heat from the wastewater. That energy gets transferred to clean water, which is then sent back to provide radiant heat and hot water for everyone in the Village. This is one reason that residents have cut their household greenhouse gas emissions by three-quarters.

The energy plant emits no odor or toxins, but its exhaust flues have been turned into public art: five stainless steel pipes reach several stories into the sky, like the outstretched fingers of a giant robot hand. The designers Bill Pechet and Stephanie Robb fitted the flues with LED lights, so that when energy output is high, the steam puffing from them is tinted with a hot-pink glow. Once upon a time, smokestacks symbolized all that was toxic and unpleasant about inner cities. Not anymore. These pink fingertips are a reminder that residents are heating their homes, in part,

with their own bodies

.

This model has begun to realize the aspiration contained in Bjarke Ingals’s power-producing mountain: a system where energy production, consumption, and human experience are drawn into a hedonic loop. But it suggests that we don’t need grand architectural metaphors to solve the challenges posed by human settlements. Real power lies not in singular objects, but in the sinew and systems and invisible relationships that run through everything, from emotions to urban geometry to systems of energy distribution. We have only begun to understand the potential of these overlapping systems, but we do know that when regular people and city builders alike embrace complexity and the inherent connectedness of city life, when we move a little closer, we begin to free ourselves from the enslaving hunger for scarce energy. We can live well and save the world at the very same time.

12. Retrofitting Sprawl

First they built the road, then they built the town

That’s why we’re still driving round and round

—Arcade Fire, “Wasted Hours”

There is a rash of studies under way designed to uncover the bad consequences of overcrowding. This is all very well as far as it goes, but it only goes in one direction. What about undercrowding? The researchers would be a lot more objective if they paid as much attention to the possible effects on people of relative isolation and lack of propinquity. Maybe some of those rats they study get lonely too.

—William H. Whyte

There is a problem with almost all the urban innovations I have been describing, and a creeping disparity at play in cities that borrow ideas from places like Bogotá, Paris, Vancouver, and Copenhagen. Jeremy Bentham would call this problem a failure to maximize utility. Ethicists would call it a problem of equity. It is both. The problem is that the happy city’s matrix of freedom, rich public spaces, leisure time, and safe streets is not much use to people like Randy Strausser and his family, or anyone else who lives far from denser, more connected places. As the wealthy recolonize downtowns and inner suburbs, and as property values rise accordingly, millions of people are simply being excluded. Meanwhile, many of these improvements are next to impossible to pull off in the city of dispersal and segregated functions, whose systems and forms are too inflexible to accommodate them and too stretched to make the civic investments affordable. This unfairness, and its intractability, gnawed at me until the afternoon I met a die-hard suburbanite named Robin Meyer.