Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (34 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Having arrived by way of Houston, to me the road felt as upside down as the bus system.

If you saw a road like this in Northern Europe or, say, Portland, you’d assume it was the product of some civic committee’s carbon reduction plan: a tool for nudging people out of their cars for the good of polar ice caps and future generations. This was not the case in Bogotá. The entire system—the upside-down road, the ultramodern bus station, the monumental library, the bike lanes, and the TransMilenio itself—had only one purpose. They were a

happiness

intervention.

Embedded within this landscape are lessons for wealthy cities in an era when budgets will be tight and resources scarce, and when every design decision will inevitably produce clear sets of winners and losers. We can learn from Bogotá because of the way its political leaders chose to act during a few short years, in a time of psychic crisis.

The Worst City in the World

When I began this story, I told you about Bogotá’s legendary decline. Colombia spent the last decades of the twentieth century mired in a civil war that left citizens caught between leftist guerrillas, government soldiers, and paramilitary forces. The chaos had crept across jungles and plantations until it infected the capital. How bad was it? Eighty thousand refugees poured into the shanties on the city’s edges every year, pushing the population to close to eight million. Those lucky enough to find jobs took hours getting there, stewing under the Andean sun inside a battered fleet of private minibuses whose rainbow colors did not make up for their stunning griminess or inefficiency. There was no public transit system worth taking, and the roads were choked with congestion. The air was a toxic soup. The city ate people’s time and chewed on their good nature. People were afraid of one another. In 1995 alone, there were 3,363 murders (a rate of 60 dead for every 100,000 people, or 10 murders a day) and 1,387 traffic deaths. The psychological landscape was depressing: three-quarters of Bogotanos thought that life was just going to get worse. Pundits dismissed the city as terminally ungovernable.

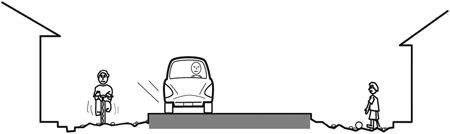

In developing-world cities with limited resources, roads are first improved by paving them for the few who drive cars, while the majority who do not drive must negotiate the mud and rubble on the shoulder …

Geometry of Equity

… But on Bogotá’s Alameda El Porvenir, the paved promenade is reserved for pedestrians and cyclists, while cars are relegated to the edge.

(Dan Planko)

The incivility and violence even seeped into the mayoral campaigns. During a televised debate between candidates Antanas Mockus and Enrique Peñalosa, a raucous student audience stormed the stage, and Mockus was caught on film brawling with the interlopers.

Peñalosa and Mockus offered Bogotans two radically different visions for urban salvation. In many ways, they represent opposite answers to a critical question: Do you save a broken city by fixing its hardware, its public space and infrastructure, or do you save it by fixing its software—the attitudes and behavior of its citizens? When Mockus won the mayor’s seat in 1995, Bogotans got a powerful and sometimes bizarre taste of the latter approach.

The City as Classroom

Antanas Mockus, the son of Lithuanian immigrants, was regarded as slightly odd, even by his admirers. He sported a bowl cut and a chinstrap beard and lived with his mother. He had been president of Colombia’s National University until the day he dropped his trousers and mooned an auditorium of unruly students. The move, which he called an act of “symbolic violence,” cost Mockus his job, but it afforded him a sudden celebrity status that helped propel him to the mayor’s seat. When he won the election, Mockus claimed all of Bogotá as his classroom. “I was elected to build a culture of citizenship,” he told me later. “What is citizenship? The notion that along with human rights, we all have duties. And the first priority is to establish respect for human life as the main right and duty of citizens.”

Bogotá had never seen a teacher like this. Mockus sent more than four hundred mimes out onto the streets to make fun of rude drivers and pedestrians. He handed out stacks of red cards so that, like soccer referees, people could call out antisocial behavior rather than punching or shooting each other. He invited people to turn in their guns on voluntary disarmament days, and fifteen hundred firearms were ceremonially melted down to make baby spoons. (Only one in one hundred of the city’s guns were retrieved, but surveys found the exercise had the effect of making many people

feel

safer and less agressive.)

Mockus actually took to dashing about the city in cape and tights as “Super Citizen” to illustrate his new code of civility, but his outlandish social marketing campaigns were supported by action. He brought in tough new rules against patronage appointments at city hall. He fired all the city’s transit police, owing to the department’s well-known bribability. It was Mockus who hired Guillermo Peñalosa, his opponent’s brother, as his parks czar and empowered him to expand both the parks system and the hugely popular Ciclovía Sunday street-closure program. Upon demonstrating his commitment to clean government, Mockus actually invited citizens to pay 10 percent more property tax to help the city deliver more services. Remarkably, more than sixty thousand households volunteered. Unorthodox as his methods were, Mockus did build a new culture of respect. Those methods may have even prepared citizens for their next mayor, who would test their very ideas of who and what the city was for.

The Urban Equity Doctrine

When Mockus quit his post to run for president in 1997, the murder, crime, and accident rates had begun to fall, but Bogotá’s physical and functional problems—congestion; pollution; and a critical lack of schools, safe streets, and public space—were still acute. The city had begun to change its mind, but it was being held back by its body.

Enrique Peñalosa, who finally won the mayor’s seat on his third try, insisted that there was an inherent connection between urban form and culture. It was not enough, he felt, to teach people a new citizenship of respect. The city itself had to manifest that philosophy in its forms, systems, and services.

“Only a city that respects human beings can expect citizens to respect the city in return,” he said in his inauguration speech. He promised that he would use his term to build that respect into the city, using concrete, steel, leaf, and lawn.

At the start of this book I credited Enrique Peñalosa with a big and simple idea: that urban design should be used to make people happier. Peñalosa is indeed a student of the happiness economists, but his program for Bogotá was grounded in a specific interpretation of well-being that, by its nature, threatens to make many urbanites uncomfortable. It asks: Who should share in the public wealth of the city? Who should have access to parks and beautiful places? Who should have the privilege of easy mobility? The questions are as much political as philosophical. Indeed, they were formed in a place and time where every big idea was political, though most were more likely to lead to revolution than urban innovation.

The Peñalosa brothers were born in the 1950s and raised in upper-middle-class privilege in Bogotá’s leafy north end, but they were made acutely aware of their country’s grinding inequities by their father, also named Enrique, who administered Colombia’s Agrarian Reform Institute. He periodically loaded Enrique junior and his brother Guillermo into a Jeep and carried them into the countryside, where, in a medieval anachronism, millions of peasants still worked the land for Colombia’s elite landowners. Enrique senior performed the work of a government-sanctioned Robin Hood, taking land from the rich and redistributing it to the ragged poor who worked it. The journeys imprinted on the boys a sense of familial mission. Since they happened to attend school with the children of the landowning elite, young Enrique and Guillermo found themselves defending their father in playground fistfights. Enrique went on to study economics, and although he wrote a book he unambiguously titled

Capitalism: The Best Option

, he continued to see city life through the lens of equity.

It could barely be otherwise. The city was just as unfair as the Colombian countryside. The biggest green space in the city was a private country club. Well-to-do residents, including Peñalosa’s own neighbors, fenced off their neighborhood parks to keep out the riffraff. Merely walking was a challenge because Bogotá’s sidewalks had disappeared under parked cars, and hawkers had completely taken over downtown plazas. The most visible injustice lay in the way that Bogotá apportioned the right to get around. Only one in five Bogotan families owned a car, but the city was increasingly using the highway-fed North American metropolis as its role model, building more road space and leaving drivers, cyclists, and bus riders to duke it out on the open road.

Before Peñalosa’s election, Bogotá had been getting technical and planning advice from the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA). This was not unusual. Poor cities often accept help from such international aid agencies. Nor was it surprising that in its new development plan for the city, JICA had prescribed a vast network of elevated freeways to ease Bogotá’s congestion. The private car and progress were symbolically intertwined. The plan infuriated the new mayor—not just because JICA’s $5 billion plan was so transparently tailored to benefit Japan’s auto industry, but because Bogotá’s elite were so keen on it as well.

“We think it’s totally normal in developing-country cities that we spend billions of dollars building elevated highways while people don’t have schools, they don’t have sewers, they don’t have parks. And we think this is progress, and we show this with great pride, these elevated highways!” he complained later.

But Bogotá would not build those elevated highways. Peñalosa began his term by scuttling the plan. He also jacked up gas taxes by 40 percent and sold the city’s shares in a regional telephone company and a hydro power utility. He poured the revenues into an aggressive agenda that put public space, transportation, and architecture to the task of improving the urban experience for everyone. His administration bought up undeveloped land on the edge of the city to prevent speculation and ensure that new neighborhoods would get affordable housing with services, parks, and greenways. He built dozens of new schools and hundreds of nurseries for toddlers. He supercharged the expansion of the parks system begun by his brother and Mockus, creating a stunning network of six hundred parks, from neighborhood nooks to Simón Bolívar, a central park more vast than Central Park. He planted a hundred thousand trees. He built three monumental new libraries in the poorer parts of town, including the one I had seen on my ride toward El Paraíso.

All this was in service of a philosophy of radical fairness.

“One of the requirements for happiness is equality,” Peñalosa told me as we rode down a side street during the election campaign in 2007. He talked so fast I had to strap a microphone to my handlebars so I could catch his words. “Maybe not equality of income, but equality of quality of life and, more than that, an environment where people don’t feel inferior, where people don’t feel excluded.”

Peñalosa pulled his bike to the curb and slapped one of the thousands of bollards that he had planted along city sidewalks. These bollards were the most symbolic salvo in his so-called war on cars. Before his term, these sidewalks would have been blocked by illegally parked cars. Not anymore. The posts stood like sentries, and indeed, the sidewalk was open and thrumming with people.

“These bollards show that pedestrians are as important as people with cars. We are creating equality; we are creating respect for human dignity. We’re telling people, ‘You are important—not because you’re rich, but because you are human.’ If people are treated as special, as sacred, they behave that way. This creates a different kind of society. So every detail in a city must reflect that human beings are sacred. Each detail!”

Later he pointed out two workmen in overalls, pedaling along one of his bicycle roads on Bogotá’s wealthy north end. “See those guys?” he said, nodding. “My bikeway gives them a new sense of pride.”