Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (31 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Britton insisted that without actually riding a bike, it was impossible to understand how the shared bicycle was transforming Paris. He checked the tires on a second bike. Fine. He adjusted the seat. Good. I poked my credit card into the kiosk, pulled my bicycle from its dock, and we rolled out into the Paris traffic, sans helmet, like everyone else. I followed Britton down a narrow side street, we hit Boulevard du Port-Royal, and all hell broke loose. Taxis bounced past like cartoon go-karts. Delivery trucks and motorbikes jostled frenetically. Bus engines screamed as they sucked at the warm air. At first I was disoriented and scared. I had been warned about the pathological aggression of Parisian drivers, and the streets were still full of them.

But Britton and I were not the only ones on two wheels. There were dozens of other Vélib’ users around us. There were so many of us out there that drivers had to pay attention. They had to make room. In

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

, Jane Jacobs described the ballet that takes place on crowded sidewalks as people make eye contact and find their way around one another. I felt a similar if supercharged dynamic coming to life in Paris’s traffic lanes. With cars and bikes and buses mixed together, none of us could be sure what we would find on the road ahead of us. We all had to be awake to the rhythm of asymmetrical flow. In the contained fury of the narrow streets we were forced to choreograph our movements, but with so many other bicycles flooding the streets, cycling in Paris was actually becoming safer. As more people took to bicycles in Vélib’s first year, the number of bike accidents rose, but the number of accidents per capita fell. This phenomenon seems to occur wherever cities see a spike in cycling: the more people bike, the safer the streets get for cyclists, partly because drivers adopt more cautious habits when they expect cyclists on the road. There is safety in numbers.

*

I left Britton with a high five and peeled onto Rue Monge, heading toward the Seine.

Between lights and lane changes, through windshields and helmet visors I caught split-second glances of turned heads, nods, angled shoulders—all clues to drivers’ intentions. I found my place in the stampede, waving a hand, pointing, moving into open ground, claiming space as I wound my way downhill, across the Seine. I kept riding as the sun fell and the slate roof tiles turned pink. I barreled toward Bastille and the monument to the Revolution of 1830. There, atop the great copper column, the gold figure of Auguste Dumont’s Spirit of Freedom was leaping into flight, holding his broken chains to the sky. The last rays of the sun exploded from his wings. The roundabout beneath the monument was a spinning whorl of headlights. I joined them, pedaling hard to keep up with the circling taxis and tour buses and motorbikes.

It was absolutely thrilling. I felt free, like Robert Judge the winter rider. But the elements that made this ride thrilling also happened to render it a travel mode unavailable to most other people. You have to be strong and agile to ride a bicycle in city traffic. You need excellent balance and vision. (Children and seniors, for example, have worse peripheral vision than fit adults, and more trouble judging the speed of approaching objects.) Most of all, you must possess a high tolerance for risk. Even the blood of adventurous riders gets flooded with beta-endorphins—the euphoria-inducing chemical that has been found in bungee jumpers and roller-coaster riders—not to mention a stew of cortisol and adrenaline, the stress hormones that are so useful in moments of fight and flight, but toxic if experienced over the long term.

The biologist Robert Sapolsky once said that the way to understand the difference between good and bad stress is to remember that a roller-coaster ride lasts for three minutes rather than three days. A superlong roller coaster would not only be a lot less fun but poisonous. I personally like roller coasters, and I loved the challenge of riding in the Paris traffic. But what is thrilling to me—a slightly reckless, forty-something male—would be terrifying for my mother or my brother or a child.

So if we really care about freedom for everyone, we need to design for everyone—not just the brave. This means we have got to confront the shared-space movement, which has gradually found favor since the sharing concept known as the

woonerf

emerged on residential streets in the Dutch city of Delft in the 1970s. In the

woonerf

, walkers, cyclists, and cars are all invited to mingle in the same space, as though they are sharing a living room. Street signs and marked curbs are replaced with flowerpots and cobblestones and even trees, encouraging users to pay more attention. It’s a bit like the vehicular cyclist paradigm, except that in a

woonerf

, everyone is expected to share the road.

*

Before his death in 2008, Hans Monderman, a Dutch traffic engineer, achieved cult status among road wonks for exporting the shared-space concept from Dutch back streets onto busy intersections. Monderman removed road markings and signs to force all travelers to think and communicate more with one another. He insisted that such shared spaces were more safe

because they felt less safe.

As in

woonerven

, pedestrians and cyclists who entered Monderman’s shared spaces were confronted with an uncertainty they could solve only by heightening their awareness of other travelers, establishing eye contact, and returning to the social rules that governed movement in busy places before cars took over. When the journalist Tom Vanderbilt joined him in the town of Drachten, Monderman actually closed his eyes and walked

backward

into a busy four-way crossing to prove his point. Drivers avoided him because they were already looking for surprises. When he heard that residents of the area did not feel safe crossing his shared-space intersections, Monderman was pleased. “I think that’s wonderful,” he told Vanderbilt. “Otherwise I would have changed it immediately.”

Accidents and injuries plummeted around Monderman’s intersections, but he wasn’t recording anyone’s stress levels. And there is a vast difference between safe travel and travel that feels safe. Not everyone is as brave or agile as the hero cyclist or the backward-walking traffic expert. If you really want to give people the freedom to move as they wish, you must go beyond accident statistics to consider how people actually feel about moving.

Traffic planners learned this in Portland, Oregon, a city that has spent two decades trying to coax people onto bikes. The city painted bike lanes along busy roads before the turn of the century. But by the mid-2000s the lanes remained mostly empty most of the time. Roger Geller, the city’s bicycle coordinator, looked at surveys of the city’s commuters and realized that they were building infrastructure for a rare species. Only about 5 percent of Portlanders were strong and fearless enough to negotiate most busy streets by bicycle. Another 7 percent of the population were enthused and confident enough to try the on-street bike lanes. Nobody else had the moxie to ride amid all that fast-moving metal. About a third of the population fell into what Geller called the “no way, no how” group: people who would never be into cycling.

“That made me just really depressed,” said Geller, but then he realized that close to 60 percent of the population fell into a group he called the “enthused but concerned.” These were people who were interested in cycling but worried about the difficulty, the discomfort, and the danger. They would cycle only if the experience was as safe and comfortable as riding in a car or a bus. So Geller and his colleagues set out to create a network of “low-stress” bikeways that either physically separated cyclists from cars or slowed cars down past the speed of fear on shared routes. It worked. Commuting by bike more than doubled in Portland between 2000 and 2008. But their investment, and the behavior change they engineered, were almost insignificant compared with the European cities where Portland found its inspiration.

A City of Reassurance

What happens when you build mobility systems entirely around safety? I found out the morning I arrived in Houten, a design experiment set amid the soggy pastures of the Dutch lowlands.

I stepped off the train, eyes blurry with an Amsterdam-size hangover, and found a bustling downtown without a car in sight—just throngs of white-haired senior citizens wheeling past on bicycles, their baskets loaded with shopping. I was greeted at Houten’s city hall by the mild-mannered traffic director, Herbert Tiemens, who insisted that we go for a ride. He led me down Houten’s main road, which was not actually a road but a winding path through what looked like a golf course or a soft-edged set from

Teletubbies

: all lawns and ponds and manicured shrubs. Not a car in sight. We rolled past an elementary school and kindergarten just as the lunch bell rang. Children, some of whom seemed barely out of diapers, poured out, hopped on little pink and blue bicycles, and raced past us, homeward. It was like Vauban, only softer, safer, calmer.

“We are quite proud of this,” Tiemens boasted. “In most of the Netherlands, children don’t bike alone to school until they are eight or nine years old. Here they start as young as six.”

“Their parents must be terrified,” I said.

“There’s nothing to fear. The little ones do not need to cross a single road on their way home.”

Once upon a time, Houten was a tiny village clustered around a fourteenth-century church. But in 1979 the Dutch government declared that Houten needed to do its part in absorbing the country’s exploding population. The hamlet of five thousand needed to grow by ten times in twenty-five years—an expansion similar to what many American suburbs would experience. Faced with such an overwhelming change, the local council adopted a plan that turned the traditional notion of the city inside out.

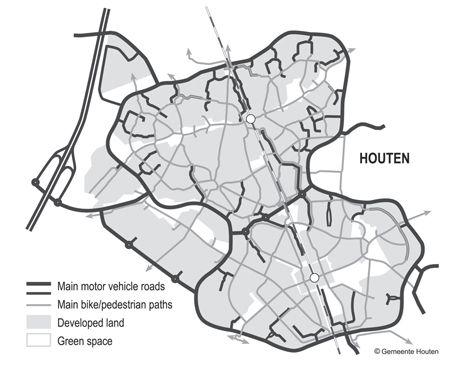

The new Houten was designed with two separate transportation networks. The backbone of the community is a network of linear parks and paths for cyclists and pedestrians, all of which converge on that compact town center and train station (and, incidentally, a plaza laid out with the same dimensions as Siena’s Piazza del Campo). Every important building in the city sits along that car-free spine. If you walk or cycle, everything is easy. Everything feels close. Everything feels safe.

The second network, built mostly for cars, does everything it can to stay out of the way. A ring road circles around the edge of town, with access roads twisting inward like broken spokes. You can reach the front door of just about every home in town by car, but if you want to drive there from the train station, you need to wend your way out to the ring road, head all the way around the edge of the city, and drive back in again.

Where bicycles and cars do share roads, signs and red asphalt make it clear that cyclists have priority. It is common to see cars inching along behind gaggles of seniors on two wheels.

The result of this reversing of the transportation order? If you count trips to the train station, two-thirds of the trips made within Houten are done by bike or on foot. The town has just half the traffic accident rate of similar-sized towns in the Netherlands and a tiny fraction of the rate found in most American towns. Between 2001 and 2005 Houten saw only one person killed in traffic—a 73-year-old woman on her bike, crushed by an impatient garbage-truck driver. If it was a comparably sized American town, that number would have been twenty times as high.

A Town Built for Children

The Dutch suburb of Houten is crisscrossed with paths for cyclists and pedestrians, while roads for cars lead only out to the town’s ring road.

(Gemeente Houten / José van Gool)

By the end of the day in safe town, I could barely keep my eyes open. Houten was as sedating as a glass of warm milk at bedtime. This was, of course, the point. The town was

supposed

to be dull: it was the kind of place where young couples moved to have kids, just as North Americans move to quiet cul-de-sacs on the edge of suburbia. Old folks moved in, too. The market streets were packed with them, gliding back and forth on bicycles loaded with groceries and grandchildren. The place is so popular with buyers young and old, it is currently being doubled in size, its ring road looping around a second town center and train station.

The difference between Houten and North American commuter towns is that Houten actually makes good on its promise of safety, security, and good health. If protecting children from harm was really a priority in wealthy economies, we could have built ten thousand Houtens rather than ten thousand Weston Ranches in the past thirty years.

The downside? The reversed road scheme did almost nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared with other Dutch towns, because people who

did

drive had to take longer routes to go wherever they were headed (though emissions were still much lower than in North American cities). This reflects the externalities cities always experience when they adopt one grand solution to their problems.

Redesigning for Freedom