Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (27 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

If you have ever flown a spaceship through an asteroid belt or driven the Santa Ana Freeway from Anaheim to Los Angeles on a Friday evening, you will understand and have benefited from the heightened focus and alertness offered by the full-on adrenal rush. It can be thrilling in the short term, but if you bathe in these hormones for too long, they can be toxic. Your immune system will be compromised, your blood vessels and bones will weaken, and your brain cells will begin to die off from the stress. Chronic road rage can actually alter the shape of the amygdalae, the brain’s almond-shaped fear centers, and kill cells in the hippocampus.

This is part of the reason why urban bus drivers get sick more often, miss work more frequently, and die younger than people in other occupations. One stress-medicine specialist, Dr. John Larson, reported that many of his heart attack patients had one thing in common: shortly before their hearts gave out, they had been enraged while driving. No wonder people start to report steady drops in life satisfaction the more their commute time exceeds Mokhtarian’s utopian sixteen minutes, even if they don’t attribute their misery to their commute.

†

Cars once promised us unparalleled freedom and convenience, but despite fantastic investments in roads and highways, and the almost complete configuration of North American cities to favor automobile travel, commute times have been getting steadily longer. Americans, for example, clocked in relatively the same average daily commute times for years—about forty minutes round-trip, not including time spent on other errands—since as far back as 1800. But the average American now spends more than fifty minutes commuting. Return commute times have shot past sixty-eight minutes in the New York megalopolis, seventy-four minutes in London, and a whopping eighty minutes in Toronto. Dozens of studies have now confirmed beyond doubt what Atlantans know from experience: the obvious solution to congestion—building more roads—simply produces more traffic, creating a hedonic treadmill of construction and frustration.

Happy Feet

One group of commuters reports enjoying themselves more than everyone else. Their route to happy mobility is simple. These are people who travel on their own steam like Robert Judge. They walk. They run. They ride bicycles.

Despite the obvious effort involved, self-propelled commuters report feeling that their trips are

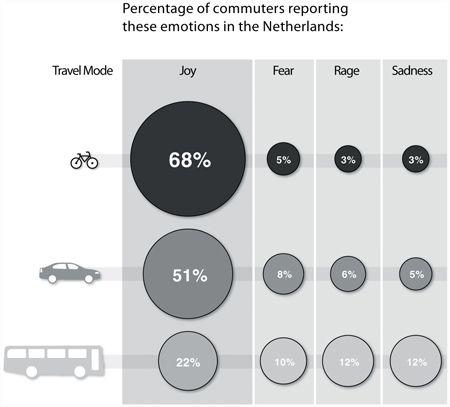

easier

than the trips of people who sit still for most of the journey. They are the likeliest to say their trip was fun. Children overwhelmingly say they prefer finding their own way to school rather than being chauffeured. These are the sentiments of people in American and Canadian cities, which tend to be designed in ways that make walking and cycling unpleasant and dangerous. In the Netherlands, where road designers create safe spaces for bikes, cyclists report feeling more joy, less fear, less anger, less sadness than both drivers and transit users. Even in New York City, where the streets are loud, congested, aggressive, and dangerous, cyclists report enjoying their journeys more than anyone else.

Why would traveling more slowly and using more effort offer more satisfaction than driving? Part of the answer exists in basic human physiology. We were born to move—not merely to be transported, but to use our bodies to propel us across the landscape. Our genetic forebears have been walking for four million years.

*

Happy Travels

In the Netherlands, where road space is provided for everyone, cyclists are by far the happiest people on the road. Public transit users report being the most miserable, as they do in most other places.

(Scott Keck; from Harms, L., P. Jorritsma, and N. Kalfs,

Beleving en beeldvorming van mobiliteit

, The Hague: Kennisinstituut voor Mobiliteitsbeleid, 2007)

How much did we once walk every day? Loren Cordain, a professor of health and exercise science at Colorado State University, tried to find out by comparing the daily energy expenditure of the average sedentary office worker to modern hunter-gatherers such as the!Kung of southern Africa. In some parts,!Kung women still spend their days collecting nuts, berries, and roots while the men hunt lizards, wildebeests, and whatever else they can track down in the desert. The women tend to walk about six miles per day and the men as much as nine, often burdened by heavy loads. The average American office worker gets barely a fifth of that exercise.

This is a troubling state of affairs, given that immobility is to the human body what rust is to the classic car. Stop moving long enough, and your muscles will atrophy. Bones will weaken. Blood will clot. You will find it harder to concentrate and solve problems. Immobility is not merely a state closer to death: it hastens it. Just spending too much time sitting shortens your life span.

We have evolved to get smarter and cheerier when we exercise, provided we can do it someplace where we aren’t burning, freezing, terrified, or in other mortal danger. Robert Thayer, a professor of psychology at California State University, fitted dozens of students with pedometers, then sent them back to their regular lives. Over the course of twenty days, the volunteers answered survey questions about their moods, attitudes, diet, and happiness. The average student walked 9,217 steps a day—much more than the typical American, though much less than a!Kung tribesman.

*

But within that volunteer group, people who walked more tended to feel more energetic and upbeat. They had higher self-esteem. They were happier. They even felt that their food was better for them.

“We’re talking about a wider phenomenon here than just walk more, feel more energy. We’re talking about walk more, be happier, have higher self-esteem, be more into your diet and also the nutritiousness of your diet,” Thayer said. The psychologist has devoted his life to the study of human moods. In test after test he proved that the most powerful way to fix a dark mood is simply to take a brisk walk. “Walking works like a drug, and it starts working even after a few steps.”

As the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard put it, there is no thought so burdensome that you cannot walk away from it. We can literally walk ourselves into a state of well-being.

The same is true of cycling, although a bicycle has the added benefit of giving even a lazy rider the ability to travel three or four times faster than someone walking, while using less than a quarter of the energy. A bicycle can expand the self-propelled travelers’ geographical reach by an astounding nine or sixteen times. Quite simply, a human on a bicycle is the most efficient traveler among all machines and animals.

Even those who endure the most severe bicycle trips seem to take pleasure in them. They feel capable. They feel free. They feel and are healthier. The average convert to bike commuting loses thirteen pounds in the first year. They may not all attain Robert Judge’s level of transcendence, but cyclists report feeling connected to the world around them in a way that is simply not possible in the sealed environment of an automobile or a bus or a subway car. Their journeys are both sensual and kinesthetic.

All this points to two problems in urban mobility. First, people are not maximizing happiness on their commutes, especially in North American cities. Second, and perhaps more urgent, most of us are overwhelmingly choosing the most polluting, expensive, and place-destroying way of moving. As I discussed in the previous chapter, cars, whether they are caught in congestion or moving fast and free, can rip apart the social fabric of neighborhoods. They are by far the biggest source of smog in most cities. They produce more greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile than almost any other way of traveling, including flying by jet airliner. It seems preposterous that we would choose a way of moving that simultaneously fails to maximize pleasure while maximizing harm. But once again, we are not all as free to choose as we might hope.

Behavior by Design

Of every one hundred American commuters, five take public transit, three walk, and only one rides a bicycle to work or school. If walking and cycling are so pleasurable, why don’t more people choose to cycle or walk to work? Why do most people fail to walk even the ten thousand daily steps needed to stay healthy? Why do we avoid public transit?

I was naive enough to ask that question of a fellow diner I met in the food court of the bunkerlike Peachtree Center in downtown Atlanta. Her name was Lucy. She had driven her car in that morning from Clayton County (a freeway journey of about fifteen miles), pulled into a parking deck, followed a skyway a few dozen paces to an elevator and then a few more to her desk. Trip time: about half an hour. Total footsteps: maybe three hundred. She flashed me a broad smile.

“Honey, we don’t

walk

in Atlanta,” Lucy told me. “We

all

drive here. I can’t say why. I guess we’re just lazy.”

Lazy? The theory doesn’t stand up. Lucy’s own commute was proof. She could not have made it to work any other way. Suburban Clayton County parked its entire bus fleet in 2010.

*

In the midst of a cash crunch, the county just couldn’t afford to run buses through the sparsely populated dispersed city.

No, the answer to the mobility conundrum lies in the intersection between psychology and design. We are pushed and pulled according to the systems in which we find ourselves, and certain geometries ensure that none of us are as free as we might think.

Few places design travel behavior as powerfully as Atlanta. The average working adult in Atlanta’s suburbs now drives forty-four miles a day.

†

Ninety-four percent of Atlantans commute by car. They spend more on gas than anyone else in the country. In Chapter 5, I explained how the centrifugal force of Atlanta’s extensive freeway network enabled its population to spread far across the Georgia countryside—and then left them vulnerable to world-class road congestion. But in a study of more than eight thousand households, investigators from the Georgia Institute of Technology led by Lawrence Frank discovered that people’s environments were shaping their travel behavior and their bodies. They could actually predict how fat people were by where they lived in the city.

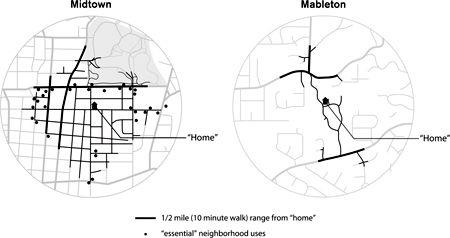

Frank found that a white male living in Midtown, a lively district near Atlanta’s downtown, was likely to weigh ten pounds less than his identical twin living out in a place like, say, Mableton, in the cul-de-sac archipelago that surrounds Atlanta, simply because the Midtowner would be twice as likely to get enough exercise every day.

Here’s how their neighborhoods engineer their travel behavior:

Midtown was laid out long before the dispersalists got their hands on the city. It exhibits the convenient geometry of the streetcar neighborhood even though its streetcars disappeared in 1949. Housing, offices, and retail space are all sprinkled relatively close together on a latticelike street grid. A quart of milk or a bar or a downtown-bound bus are never more than a few blocks away. It is easy for people to walk to shops, services, or MARTA, the city’s limited rapid transit system, so that’s what they do.

But in suburbs like Mableton, residential lots are huge, roads are wide and meandering, and stores are typically concentrated in faraway shopping plazas surrounded by parking lots. Six out of every ten Atlantans told Frank’s team that they couldn’t walk to nearby shops and services or to a public bus stop. They just didn’t have the mix. Road geometry was partly to blame. Frank and others have found that that iconic suburban innovation—the cul-de-sac—has become part of a backfiring behavioral system.

When designers try to maximize the number of cul-de-sacs in an area, they create a dendritic—or treelike—system of roads that feeds all their traffic into a few main branches. The system makes just about every destination farther away because it eliminates the most direct routes between them. Connectivity counts: more intersections mean more walking, and more disconnected cul-de-sacs mean more driving.

*

The long-distance story is not unique to Atlanta. In 1940 the average person in Seattle lived less than half a mile from a store. By 1990 the distance had grown to more than three-quarters of a mile, and it has grown since. In 2012, after Facebook and architect Frank Gehry unveiled designs for a new 10-acre base across the Bayfront Expressway from Facebook’s old base in Silicon Valley, Gehry explained that his plan strove for “a kind of ephemeral connectivity” through its single-level, open-concept floor design. But no magical configuration of the office-park geometry could make up for the fact that half of Facebook’s workers actually lived thirty miles away in dense, walkable, networked San Francisco. Facebook would just have to keep busing them in.