Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (20 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

But design influences our social life even in high-status landscapes where conditions are not so dire, and the evidence supports the old dictum that good fences make good neighbors, so much as they allow us to control our interactions. Consider the experience of Rob McDowell, a diplomat who bought a condominium on the twenty-ninth floor of the 501, a hip, design-heavy tower in Vancouver’s Yaletown district. Rob was single and had no kids, so five hundred square feet seemed quite enough, especially given the panoramic view from his floor-to-ceiling windows. He could see the ocean. He could see islands in the distance. He could look over the other towers to the forested slopes of the North Shore Mountains. When the fog rolled in, he floated above it. The place wrapped biophilic views, status, and privacy in a neat package.

“I invited all my friends up there to see the view,” he told me later. “I was so happy.”

But that changed as the months went past.

Whenever McDowell left his apartment, he would follow a hallway he shared with twenty people to an elevator he shared with nearly three hundred people. When the elevator door opened, he could never be sure whom he would see inside, but they were almost never his own neighbors. Standing a foot or two apart, well within the zone of personal space and unable to control the duration of the encounter, McDowell and his neighbors would studiously avoid eye contact, gazing up instead at the LED floor display.

*

Like Baum’s dorm residents, McDowell felt increasingly claustrophobic. His view was no salve for solitude. “You go up the elevator, into your apartment, the door closes, and there you are, stuck alone with your beautiful view,” he said. “I began to resent it.”

McDowell’s Vancouverist tower, so successful in delivering views of nature and a sense of status, was falling short as a social tool. This became clear when his life suddenly changed course.

The city had forced the 501’s developer to build a row of town houses along the podium base of McDowell’s tower. The town houses were a bit cramped, but their main doors all faced a garden and a volleyball court on the building’s third-story rooftop. McDowell noticed that the town house residents regularly played volleyball in the garden. He and his tower-living neighbors had every right to join in, but they never did. It was as though, by their proximity, the town house residents owned that space.

After some friends moved into the town houses, McDowell gave up his view and bought a unit next to them. Within weeks his social landscape was transformed. He got to know

all

his new neighbors. He joined in the weekend cocktail and volleyball sessions in the shared garden. He felt as if he had come home.

McDowell’s new neighbors were not inherently more likable or friendly than his tower neighbors. So what had drawn them together? In some ways, their behavior was predicted by decades of sociology similar to Baum’s campus studies. The front doors of the town houses all led to semiprivate porches overlooking the podium garden. They provided regular opportunities for brief, easy contact. These porches were a soft zone, where you could hang out or retreat as you wished. (What would happen if a tower dweller decided to just “hang out” in the hallway in the adjoining tower? Not only would he be bored and uncomfortable, but eventually someone would call the police.) Without realizing it, McDowell and his neighbors were testing out a law of social geometry identified by Danish urbanist Jan Gehl. In studying the way people in Denmark and Canada behave in their front yards, Gehl found that residents chat the most with passersby when yards are shallow enough to allow for conversation, but deep enough to allow for retreat. The perfect yard for conviviality? Exactly 10.6 feet deep.

Then there was the issue of social scale. Rather than bumping into any one of three hundred or so strangers each day in the tower elevator, McDowell experienced repeated contact with fewer than two dozen neighbors, making the social world of the garden more manageable, somewhat like a

fareej

, a domestic enclosure common in the Arab world that is big enough for several extended families. McDowell could remember the names of everyone who passed his door.

These new friendships are not trivial. Nine years on, McDowell babysits his neighbors’ kids and keeps spare keys for their doors. His fellow town house dwellers dominate the building’s management board. They vacation together. Where the tower pushes people apart, the town house courtyard draws them closer. He considers half of his twenty-two town house neighbors to be close friends.

“How many of them would you say you love?” I asked him the afternoon he showed me around. It was an intrusive question. He blushed, but counted on his fingers. “Love, like they were my family? Six.” This is a stunning figure, given the shrinkage that most people report in their social networks these past twenty years. “And we love our home. All of us.”

The Magic Triangle

These sentiments—loving your home and loving your neighbors—are related. John Helliwell’s most recent studies of national surveys show that the tight web connecting trust and life satisfaction also extends to the misty realm of our sense of belonging. They exist in a perfect triangle:

People who say they feel that they “belong” to their community are happier than those who do not.

And people who trust their neighbors feel a greater sense of that belonging.

And that sense of belonging is influenced by social contact.

And casual encounters (such as, say, the kind that might happen around a volleyball court on a Friday night) are

just as important

to belonging and trust as contact with family and close friends.

It is hard to say which condition is lifting the others—Helliwell admits that his statistical analysis demonstrates correlation rather than causation—but what is strikingly apparent is that trust, feelings of belonging, social time, and happiness are like balloons tied together in a bouquet. They rise and fall together. This suggests that it has been a terrible mistake to design cities around the nuclear family at the expense of other ties. But it also suggests that even the high-status, deeply desired, uniquely biophilic brand of verticalism embodied by Vancouverism and McDowell’s high-rise apartment is not a panacea. Helliwell produced a report in which people living in the city’s vertical core rated their happiness significantly lower than people living in most other parts of the city. (The Vancouverists are far from miserable: downtown dwellers rated their life satisfaction between 7 and 7.5 on a scale of 1 to 10—about as happy as most Americans—but less dense neighborhoods scored more than a point higher.)

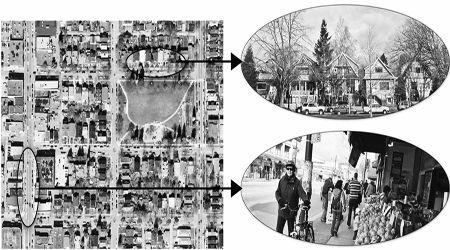

Vancouver just can’t escape the persistent link between domestic design and conviviality. People living in Vancouver’s downtown peninsula simply don’t trust their neighbors as much as people living in neighborhoods where more people live on the ground.

*

The Vancouver Foundation, the city’s largest philanthropic organization, surveyed people about their social connections. People living in towers consistently reported feeling more lonely and less connected than people living in detached homes. They were only half as likely to have done a favor for a neighbor in the previous year. They were much more likely to report having trouble making friends.

Many people love tower living, and many are skilled enough to build a social world in the tower city. They use the tools of the city—the coffee shop, the community center, the social or sports club, the neighborhood garden. They turn uncomfortable intimacies into opportunities. (John Helliwell insists on chatting with strangers in elevators, for example.) Increasingly, they use online tools and mobile applications to find each other. But for those of us who just bumble along, letting our social lives happen to us, the power of scale and design to open or close the doors of sociability is undeniable. The geometries of conviviality are not simple. We cannot be forced together. The richest social environments are those in which we feel free to edge closer together or move apart as we wish. They scale not abruptly but gradually, from private realm to semiprivate to public; from bedroom to parlor to porch to neighborhood to city, something most tower designers have yet to achieve.

The Sweet Spot Is Somewhere in Between

If you search hard enough for places that balance our competing needs for privacy, nature, conviviality, and convenience, you end up with a hybrid, somewhere between the vertical and horizontal city.

Just as McDowell and his neighbors found a rich, connected home life three stories above the surface of the earth, cities all over the world offer up surprisingly happy geometries, both by design and by accident. In Copenhagen, architect Bjarke Ingels has attempted to fuse suburban and urban attributes in one building. Ingels’s Mountain Dwellings stack eighty apartments with generous patios over eleven stories of sloping roof atop a neighborhood parking lot. Everyone gets a private “backyard” and a coveted south-facing view in a country bereft of mountains, in a district just dense enough to support decent transit.

But the happy geometry need not be so high in concept or cost. It can be found wherever scale and systems intersect with a critical density of human life. It can be found throughout the developing world, where zoning laws have not tamed the bric-a-brac mix of neighborhood housing and commerce. It can be found in Tuscan hill towns, English rail suburbs, South Pacific island villages, and the pueblos swallowed by Mexico City.

One almost-ideal urban geometry was perfected in many North American cities more than a century ago. It was invented not by utopian planners or sociologists, but by cunning men motivated by the constraints of technology and an old-fashioned wish to make as much money as they could.

After the first electrical streetcar was introduced in Richmond, Virginia, in 1887, rail lines rapidly spread across hundreds of cities, luring commuters to new streetcar suburbs from Boston to Toronto to Los Angeles. Almost no one owned a car before World War I, so land developers wishing to attract homebuyers first had to build the rail lines, then offer homes within an easy walking distance from them. Buyers also demanded shops and services and schools, and sometimes parks, all within walking range. If you didn’t offer the full package, you would have a hard time selling land. Thus, during the golden age of streetcar suburbia, property development and streetcar development went hand in hand.

“There was a perfect, organic relationship between the purveyors of transit and the purveyors of real estate for business, all of whom wanted to provide enough customers for both business and transit,” explains Patrick Condon, an urbanist at the University of British Columbia who has studied the dynamic.

The key to making a profit, said Condon, was to get that math right. The developers assumed (quite correctly, we now know) that most people are happy to walk five minutes, or about a quarter of a mile, from home to shops and streetcars. But in order to provide that critical mass of paying trolley riders and property buyers, they needed to keep residential lots relatively small. The typical street frontage for a single-family house in Vancouver’s streetcar neighborhoods was just thirty-three feet, delivering at least eight homes per acre (which makes neighborhoods from two to eight times as dense as many modern suburbs

*

). Schools were small, too, with classrooms stacked two or three stories high to make room for playgrounds.

As it turned out, the geometry of profit also created a near-perfect scale for happy living. Market streets were lively and bustling, while the residential streets behind them were quiet and leafy. Most people got their own house and yard. There were porches rather than front garages, so people could keep their eyes on the street. Kids had the freedom to walk to school. Without modern suburbia’s massive yards, wide roads, and strict segregation of uses, almost everything you needed was a five-minute walk or a brief streetcar ride away. In the streetcar city, greed helped produce density’s sweet spot.

Streetcar City 2.0

Most streetcar neighborhoods fell into decline after the 1950s. They suffered multiple wounds. Many lost their streetcars when the systems were bought up by motor interests and replaced with buses. Their ease and charm was eroded by the mass adoption of automobiles, which clogged the main streets and slowed both streetcars and buses. Freeways ripped through their vulnerable fabric. Many were abandoned by governments and wealthier citizens in the flight toward increasingly distant suburbs. Tax dollars fled. Schools and services declined. As household sizes shrank and retailers followed the flight to the urban edge, the metrics of scale, system, and human density lost their alchemic balance. But the geometry of the streetcar city has survived, and actually been improved upon, in places like Toronto, Seattle, Portland, and Vancouver.

I discovered the streetcar neighborhood almost completely by accident. My leap into the property market, buying a share of my friend Keri’s house in 2006, was driven by the most superficial aspirations. I wanted more rooms, a bigger kitchen, my own piece of ground. I was bugged that the house sat on a tiny lot—twenty-five feet by one hundred, less than a quarter of the size of the lots typically sold in the suburbs in the last three decades. The backyard was the size of a squash court. If you reached out the windows to the north or south, you could scrape the paint on the neighbor’s clapboard. At first I felt that the whole setup was a bit on the stingy side. I didn’t realize that these dimensions actually helped my house and my neighborhood achieve the delicate balance between privacy, conviviality, and biophilia. What mattered most was that house’s place in the system around it: the density of people per acre, the length of each block, the distance to the nearest market street, and the mixing of all kinds of different activities.