Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (8 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

The Stretched Life

Take Randy Strausser, a hardworking and relatively prosperous resident of the dispersed city who won the foreclosure sweepstakes. Randy and his wife, Julie, bought a California-style ranch house in Mountain House, a partially finished exurban development south of Stockton, in 2007, when the market was tanking. At the time, Mountain House was just behind Weston Ranch in foreclosures. This was great news for the Straussers. They paid half of what some of their neighbors had paid for their places. The house seemed perfect: It had high-end fixtures, high-efficiency heating and air-conditioning, and a private fenced garden. It looked out on a green belt with a creek. According to the American dream narrative of the Repo Tour, Randy should have been an extremely happy man when I met him a couple of years later.

But he was not, and his unhappiness speaks to the dispersed city’s power to fundamentally reorder social and family life. If you accept the key message from happiness science, which is that absolutely nothing matters more than our relationships with other people, it is a story worth exploring.

Part of Randy’s problem was that, like a quarter of the people in San Joaquin County, he worked over the hills in San Jose. In fact, his was a family of long-distance commuters. At dawn on any given weekday, Randy; his septuagenarian mother, Nancy; and his daughter, Kim, would all be out on the highway, often driving alone from their respective homes, crossing two mountain ranges and speeding past half a dozen municipalities to their jobs in the Bay Area, each racking up more than 120 miles round-trip. Randy gave the highway three or four hours a day, in addition to the trips he made for his job as a heating and air-conditioning specialist. With housing prices still sky-high near San Francisco, this was what one had to do to live in a detached home in a “good” community.

One evening I hopped into the passenger seat of Randy’s Ford Ranger as he left his business park office. The sun was just setting over San Francisco Bay as we made the long merge from Route 101 to Interstate 680. The stacked overpasses of the interchange arced in silhouette across a glowing sky. Randy ignored the sunset in order to focus on that first merge. He stretched his fingers and tightened them around the wheel, adjusted the Bluetooth in his ear, eyed the taillights converging on the 680, and described his typical day.

Smack the alarm off at 4:15 a.m. Shower. No breakfast. Hit the highway at five to beat the traffic. Arrive by 6:15 a.m. Eat at work. Try to be back on I-680 by 5:30 p.m. It was harder to beat the rush in the afternoons. He was lucky to get to his front door by 7:30. No coffee on the drive, no talk radio—those just made him angry, and he wanted to control his anger in order to respond rationally to the pressures of the freeway.

“But coming home to your place in Mountain House, that’s the payoff,” I offered declaratively as we flew past the office parks of Pleasanton, forty minutes in, almost halfway home.

He shook his head. On bad traffic days, when Randy got home, he would grab a hose and water the garden until he calmed down. Then he’d hop onto the elliptical trainer to straighten out his aching back. On really bad days, when the drive calcified his fatigue and frustration, Randy drove another twenty minutes to the World Gym over in Tracy. Not slowing down for chitchat with the gym crowd, he would crank the Van Halen on his old Walkman and sweat out his aggression. Then it was back home for a shower and bed.

For now, we will forget Randy’s road-induced back pain. We will put aside his irritation with other drivers and his general bitterness at having to spend so much time on the highway. (After all, not everyone minds a long commute. Randy’s mother, Nancy, told me she enjoyed the two-hour drive to Menlo Park, near Palo Alto, in her gold Lexus.) It was Randy’s relationships with the people around him that were hurt most by his long-distance life.

Randy disliked his neighborhood intensely. He couldn’t wait to get out of Mountain House. The problem had nothing to do with the aesthetics of the place. It was still as pristine and manicured as the day he and his wife moved in. It was the people who bothered him. He did not know, like, or particularly trust his neighbors. I asked him economist John Helliwell’s trust question: What were the chances that he’d get his wallet back if he happened to drop it on his street?

“I’d never see it again!” he said with a laugh. “Look, shortly after we moved in, we were burglarized. The police were the first to say we’d never see any of our stuff ever again. This happens constantly out here. Everybody turns their head away. Nobody looks out for each other.”

We Can Trust Other People More Than We Think

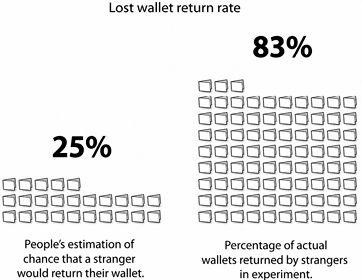

Survey respondents rate the likelihood of a stranger returning their lost wallet at only about 25 percent. But an experiment in Toronto found that among real strangers, the likelihood of return was better than 80 percent.

(Scott Keck, with data from Helliwell, John, and Shun Wang, “Trust and Well-Being,” working paper, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010)

Had Mountain House attracted a particularly untrustworthy demographic? Probably not. Randy’s mistrust actually points to the tricky twist in that lost-wallet question: your level of faith in getting your wallet back has almost nothing to do with the actual rate of wallet losses and returns in your community. The numbers are independent, just as most people’s perception of safety has more to do with the plentitude of graffiti than the density of purse snatchers. Most people’s response to the wallet question ends up having as much to do with the quality and frequency of their social interactions as it does with the actual trustworthiness of other people, Helliwell told me.

*

We may live among noble, honest, wallet-returning people, yet if we do not experience positive social interactions with them, we are unlikely to build those bonds of trust.

Randy complained that his neighbors didn’t keep an eye on one another’s homes. They didn’t chat on the sidewalks. They didn’t get to know one another.

But how would they? The urban system gave them few opportunities. There were some five thousand people living in partially finished Mountain House, but there were virtually no jobs and no services beyond a little library, a couple of schools, and a small convenience store. Most of the adults drove out of Mountain House before dawn and returned after dark, cruising, one by one, into their garages and closing the doors behind them. The only people left during the day were the kids. So Randy’s lack of trust in his neighbors was at least partly artificially induced. In stretching his daily routine, the city had sucked much of the spectrum of casual social contact right out of the neighborhood.

This is not a local phenomenon, nor is it a trivial matter.

The Social Deficit and the City

Just before the crash of 2008 a team of Italian economists led by Stefano Bartolini tried to account for that seemingly inexplicable gap between rising income and flatlining happiness in the United States, using the statistical method known as regression analysis.

*

The Italians tried removing various components of economic and social data from their models, and they found that the only factor powerful enough to hold down people’s self-reported happiness in the face of all that wealth was the country’s declining social capital—the social networks and interactions that keep us connected with others. It was even more corrosive than the income gap between rich and poor.

A healthy social network looks like the root mass of a tree. From the most important relationships at the heart of the network, thinner roots stretch out to contacts of different strength and intensity. Most people’s root networks are contracting, closing in on themselves, circling more and more tightly around spouses, partners, parents, and kids. These are our most important relationships, but every arborist knows that a tree with a small root-ball is more likely to fall over when the wind blows.

The sociologist Robert Putnam warned back in 2000 that these networks of lighter relationships had been dwindling for decades. The trend has continued. People are increasingly solitary. In 1985 the typical American reported having three people he could confide in about important matters. By 2004 his network had shrunk to two, and it hasn’t bounced back since. Almost half the population say they have no one, or just one person, in whom they can confide. Considering that this included close family members, it reflects a stunning decline in social connection. Other surveys show that people are losing ties with their neighborhoods and their communities. They are less likely to say they trust other people and institutions. They don’t invite friends over for dinner or participate in social or volunteer groups as they did decades ago. Like Randy Strausser, most Americans simply don’t know their neighbors anymore. Even family bonds are being strained. By 2004 less than 30 percent of American families ate together every night. All of these conditions are exacerbated by dispersal, as I will explain. But first, a reminder of why they constitute a happiness disaster.

As much as we complain about other people, there is nothing worse for mental health than a social desert. A study of Swiss cities found that psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, are most common in neighborhoods with the thinnest social networks. Social isolation just may be the greatest environmental hazard of city living—worse than noise, pollution, or even crowding. The more connected we are with family and community, the less likely we are to experience colds, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, and depression. Simple friendships with other people in one’s neighborhood are some of the best salves for stress during hard economic times—in fact, sociologists have found that when adults keep these friendships, their kids are better insulated from the effects of their parents’ stress. Connected people sleep better at night. They are more able to tackle adversity. They live longer. They consistently report being happier.

There are many reasons for America’s shrinking social support networks: marriages aren’t lasting as long as they used to, people work longer hours, and they move frequently (the bank-enforced exodus during the mortgage crisis didn’t help). But there is a clear connection between this social deficit and the shape of cities. A Swedish study found that people who endure more than a forty-five-minute commute were 40 percent more likely to divorce.

*

People who live in monofunctional, car-dependent neighborhoods outside of urban centers are much less trusting of other people than people who live in walkable neighborhoods where housing is mixed with shops, services, and places to work. They are also much less likely to know their neighbors. They are less likely to get involved with social groups and even less likely to participate in politics. They don’t answer petitions, don’t attend rallies, and don’t join political parties or social advocacy groups. Citizens of sprawl are actually less likely to know the names of their elected representatives than people who live in more connected places.

†

This matters not only because political engagement is a civic duty, and not just because it is one more contributor to well-being. (Which, by the way, it is: we tend to be happier when we feel involved in the decisions that affect us.) It matters because cities need us to reach out to one another as never before. A few years after convincing the world of the value of social capital, the sociologist Robert Putnam produced evidence that the ethnic diversity that is increasingly defining major cities is linked with lower levels of social trust. This is a sad and dangerous state of affairs. Trust is the bedrock on which cities grow and thrive. Modern metropolitan cities depend on our ability to think beyond the family and tribe and to trust the people who look, dress, and act nothing like us to treat us fairly, to honor commitments and contracts, to consider our well-being along with their own, and, most of all, to make sacrifices for the general good. Collective problems such as pollution and climate change demand collective responses. Civilization is a shared project.

The Lonely Everywhere

It is impossible to deny that the dispersed city has altered the ways and speeds at which we cross paths with one another. Dispersed communities can squeeze serendipitous encounters out of our lives by pushing everyday destinations beyond the walker’s reach. In that way, Mountain House is a lot like Weston Ranch. If you need anything more substantial than a slushie, you have to get into your car and drive to some other town, which is what everyone does. Randy Strausser might have the gas money, but this hypermobility alters his social landscape. That guy watering his lawn down the street is just a passing blur on Randy’s eight-mile drive to the FoodMaxx over in Tracy. He might give a nod to a couple of people in the cavernous grocery store, but chances are, he will never see them again. His network is stunted, wrapped around a social core, like the roots of a pot-bound tree.

This withering of social capital is not strictly an exurban phenomenon.

*

But a closer look at those surveys reveals the insidious, systematic power of dispersal to alter our relationships. It is a neighborhood’s place in a city, and the distance its residents travel every day, that make the biggest difference to social landscapes. The more time that people in any given neighborhood spend commuting, the less likely they are to play team sports, hang out with friends, watch a parade, or get involved in social groups. In fact, the effect of long-distance living is so strong that a 2001 study of neighborhoods in Boston and Atlanta found that neighborhood social ties could be predicted simply by counting how many people depend on cars to get around. The more neighbors drove to work, the less likely they were to be friends with one another.