Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (29 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

The Saga of “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap.

That’s how Sunbeam’s infamous “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap managed to look so smart—at least for a while. When Dunlap arrived in July 1996, Sunbeam was a struggling company. Dunlap had a reputation as a turnaround artist.

During his prior 18-month gig leading the Scott Paper Company, Dunlap’s shenanigans had helped to drive up the stock price by 225 percent, increasing the company’s market value by $6.3 billion. The company was then sold to Kimberly-Clark for $9.4 billion, with Dunlap pocketing $100 million as a going-away present. During his short stay at Scott, Dunlap fired 11,000 employees, slashed expenditures on plant improvements and research, and then sold the company to a major rival. Wall Street cheered as Scott became the sixth company sold or dismembered by Dunlap since 1983.

So, not surprisingly, the day Sunbeam announced that Dunlap would become its new CEO, its share price jumped 60 percent—the largest one-day jump in the company’s history. By the following year, the apparent turnaround had begun to impress investors. The stock, which had been $12.50 the day before Dunlap’s hiring was announced, peaked at $53 in early 1998. Dunlap was given a new contract, doubling his base salary.

Then the truth became known. On April 3, 1998, the stock plunged 25 percent when the company disclosed a loss for the quarter. Two months later, negative statements in the press about the company’s aggressive sales practices prompted Sunbeam’s board to begin an internal investigation. The investigation uncovered numerous accounting improprieties and resulted in the termination of both Dunlap and the CFO and extensive restatement of earnings from the fourth quarter of 1996 through the first quarter of 1998. The restatement wiped out nearly two-thirds of Sunbeam’s reported 1997 net income, and the company eventually filed for bankruptcy.

Improperly Writing Off Intangible Assets

. In a manner similar to the accounting treatment of plant and equipment, most intangible assets (with goodwill as a notable exception) will be amortized over a set period established by management. Under EM Shenanigan No. 4, stretching out the time horizon provides an artificial boost to income by lowering the quarterly amortization expense. And, of course, curtailing the time horizon serves to mute profits. Since this is the precise objective of EM Shenanigan No. 7, investors should be mindful of such a shortened useful life on intangible assets.

Watch for Restructuring Charges Just Before an Acquisition Closes

. Remember from the previous chapter that U.S. Robotics gave its new friend 3Com a gift by holding back hundreds of millions in revenue to be released by 3Com after the merger closed? Well, U.S. Robotics had a second wonderful welcoming gift that was just as simple to create by using one of the techniques under EM Shenanigan No. 7. Just before the merger, U.S. Robotics took a $426 million “merger-related” charge, which prevented 3Com from having to record those costs as part of normal operations after the merger. Of the total charge, $92 million was related to the write-off of fixed assets, goodwill, and purchased technology. Naturally, writing off these assets would reduce future-period depreciation and amortization expense and increase net income. What a great way to make a new friend smile!

Be Wary When Restructurings Occur with Uncommon Regularity.

Restructuring costs for streamlining operations and cost containment programs often are warranted during tough economic times. However, restructuring events should not become an every year occurrence. As we discussed in Chapter 5, “EM Shenanigan No. 3: Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities,” some companies abuse the ability to present charges below the line by recording charges for “restructuring costs” or “one-time items” in every single period. A case in point was Alcatel and its restructuring charges in just about every quarter for years on end. After a while, investors must question whether companies actually know the difference between nonrecurring and recurring. If a company incurs a certain type of cost every year, it should be shown with all the other recurring operating items.

2. Improperly Recording Charges to Establish Reserves Used to Reduce Future Expenses

In the first section of this chapter, we discussed how companies record an expense today in order to prevent past expenditures (which remain as assets on the Balance Sheet) from becoming future expenses. In this section, we highlight a similar trick in which companies record an expense today in order to keep future expenditures from being reported as expenses. With this trick, management loads up the current period with expenses, both taking some from future periods and even making some up. In so doing, when the future period arrives, (1) operating expenses will be underreported, and (2) bogus expenses and the related bogus liabilities will be reversed, resulting in underreported operating expenses and inflated profits. Let’s examine those two results in more detail.

Using Restructuring Charges Today to Inflate Operating Income Tomorrow

Just as AOL was anxious to remove the $385 million in deferred marketing costs from future periods’ amortization expense, any company that is taking a restructuring charge (such as laying off workers) might consider padding the total dollars written off in order to lower future-period operating expenses. Thus, salary expense to employees who are laid off today will decline in future periods, as any future severance payments received will be bundled into today’s one-time charge. The result: future periods’ above-the-line operating expense disappears, and the current period’s below-the-line restructuring charge increases by that same amount. But remember, investors generally ignore restructuring charges, so the more a company throws into the charge-off, the better. More below-the-line expense and less above-the-line is viewed as a win-win situation.

Watch for Dramatic Improvement in the Numbers Right After the Restructuring Period

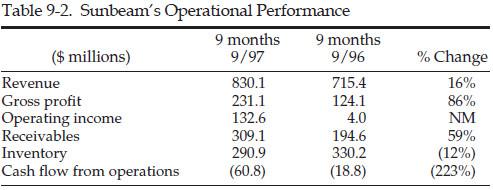

. Let’s return to Sunbeam to see the huge impact on future earnings from a prior restructuring charge. As shown in Table 9-2, Sunbeam’s operating income surged to $132.6 million in the nine months following the restructuring charge, from $4.0 million in the prior-year period. Consider the impact of Sunbeam’s accounting policy changes shortly after Dunlap took the reins. During the December 1996 quarter, Sunbeam recorded a special charge of $337.6 million for restructuring and another $12 million charge for a media advertising campaign and “one-time expenditures for market research.” According to the SEC lawsuit, the 1996

restructuring charge was inflated

by at least $35 million, and Sunbeam also improperly created a $12 million litigation reserve.

Watch for “Big Bath” Charges During Difficult Times.

Perhaps there is no better time to record huge charges than when the market is in a downturn. Since during these times investors are more focused on how companies will emerge from the downturn, large charges are rarely frowned upon; indeed, they are often seen as a positive. Amazingly, during the 2002 market slump, 40 of the 54 largest U.S. utility companies (74 percent) recorded “unusual” charges (according to a survey by CFRA). As we discussed earlier, it is not difficult for management to use these charges to inappropriately write off productive assets or establish bogus reserves.

Creating a Larger-Than-Needed Restructuring Reserve and Inflating Future Earnings by Releasing the Reserve

The previous chapter explained how companies tend to obsess over reporting smooth and predictable earnings. Remember the example of Freddie Mac reserving so much that it got caught before it was ever able to release more than $4 billion that it had squirreled away? This technique of creating and releasing reserves, as needed, works great for management playing the opposite game.

Using a Restructuring Reserve to Smooth Earnings.

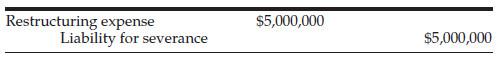

When a company takes an appropriately sized restructuring charge (e.g., when it plans to lay off 100 people and takes a charge for only those 100), salary expense will be shifted to the earlier period and classified as below the line. That intraperiod movement to below the line works fine for most, but some managements become too greedy and use a second (and unethical) trick. When it is planning to lay off employees, management instead takes an inappropriately large restructuring charge (e.g., it plans to lay off 100 people but announces and takes a charge for 200). By announcing a 200-person layoff when 100 would be sufficient, management doubles the restructuring expense and liability. Let’s assume that management provides a $25,000 severance package for each person who is laid off. That works out to $2.5 million if management acts ethically; alternatively, by doubling the 100 employees to 200, it takes a $5 million charge, as shown in the following entry:

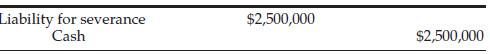

The company then pays out the promised $25,000 to each of the 100 folks who are now out of work and makes the following accounting entry:

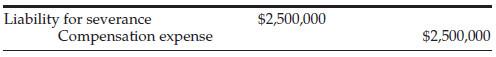

Of course, another $2.5 million still remains in the liability, with no more expected severance obligations. So, management takes the plunge and releases the bogus reserve in the liability account, reducing compensation expense. This sure seems like an enticing trick for an unethical company that needs a few more pennies to beat Wall Street’s estimates. We call this “the gift that keeps on giving.”

Lucent Fills the Cookie Jar

. Consider Lucent’s focus on using reserves with restructuring charges in the late 1990s. It put aside far more than it needed to cover the restructuring expenses, and the excess reserves then helped the company to smooth out choppy earnings. Over three years, Lucent allegedly lowered its expenses and pumped up earnings by releasing $442 million from reserve accounts.