Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) (16 page)

Read Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Lilian Stoughton Hyde

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

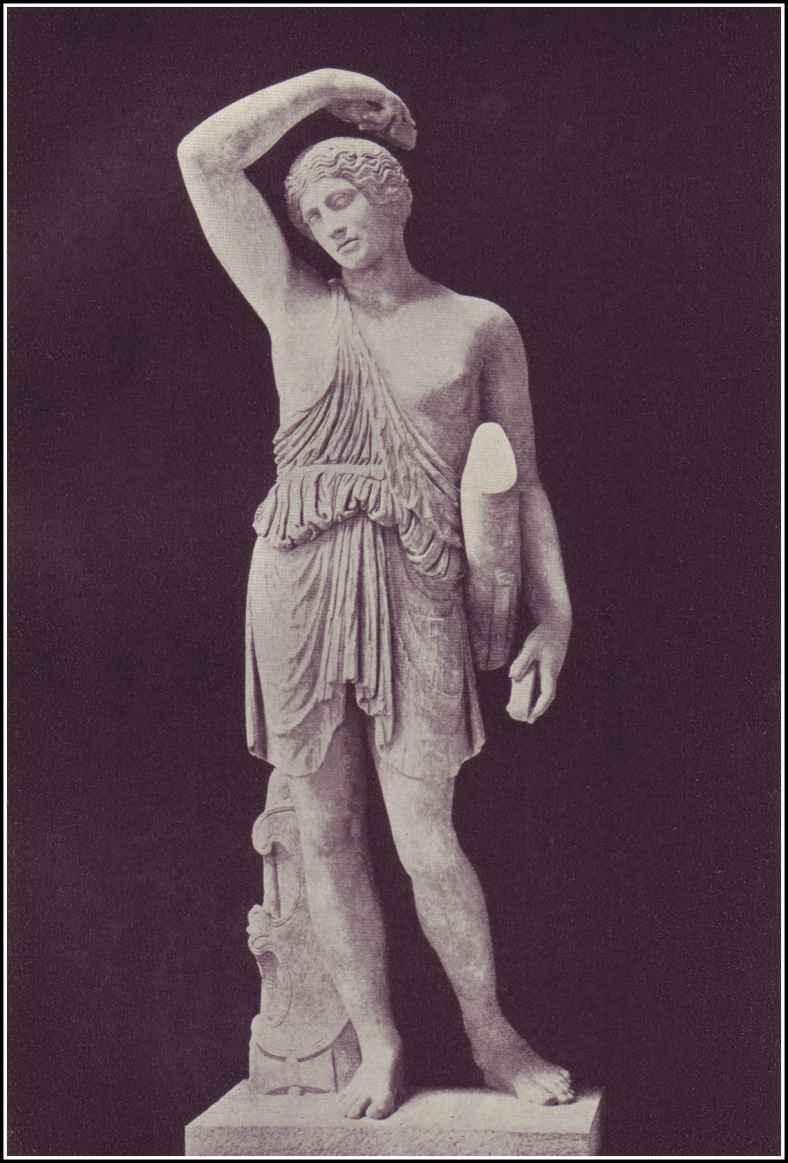

DIANA OF THE HIND

The Fifth Labor

The Destruction of the Stymphalian Birds

K

ING

E

URYSTHEUS

now sent Hercules to drive away the Stymphalian Birds.

The valley of Stymphalus was often visited by enormous flocks of strange birds. These birds did great damage to the crops and to the herds, for it was an easy matter for them to kill a sheep or a cow and feed on the carcass. Besides, they had been known to carry off children. These birds had sharp claws of iron, and feathers which were sharp at the quill end like the point of an arrow, and which they had the power of throwing at their enemies, as the porcupine was supposed to throw its quills. Of course these birds must have been a thousand times worse than any porcupine, because they could fly through the air, and throw their feathers from above. Their nests were in a thick, dark wood, in the midst of which was a pool.

Instead of trying to fight birds like these with his bow and arrows, or his club, or his hunting spears, Hercules thought of another plan. He went quietly to the edge of the pool, and holding his bronze shield above his head to protect himself from the birds' feathers, he rang a large bell, and at the same time beat upon the shield with his lance.

The birds, frightened at the sudden clattering noise, flew up in such numbers that it seemed as if a great dark cloud had come over the sky. As they flew over the head of Hercules, their sharp feathers fell fast, rattling on the shield, and tearing the leaves of the surrounding trees into strips.

Hercules kept on ringing the bell and beating the shield till every bird had left the wood, except a half-dozen that had stayed behind to watch from the tops of the tallest trees. These few that were left, he easily shot with his poisoned arrows.

After this the birds built their nests on the Island of Mars, and never came back to trouble the valley of Stymphalus.

The Sixth Labor

The Cleaning of the Augean Stables

T

HE

next labor of Hercules was the cleaning of the Augean stables. King Eurystheus told him that he must do this work alone, and do it in one day.

King Augeas was a son of Helios, and one of the heroes who sailed with Jason on the Quest of the Golden Fleece. He was a king of Elis. His herds were so large that, toward sundown, when the cattle came up to the stables from their pastures, they seemed to pour across the plains endlessly, as the fleecy white clouds, driven by the west wind, sometimes roll across the sky.

Among these cattle were twelve snow-white bulls, which were sacred to Helios. One of them, the leader, was so very white that he shone among the other cattle, like a star, and had been named Phaethon, after the son of Helios. When wild beasts—panthers or wolves or even lions—came down from the mountains to attack the herds, as they often did, the twelve white bulls always went first to drive them back, lowering their curly foreheads, shaking their sharp horns, and bellowing, as they went, in a way to frighten any beast that ever roamed the plains.

When Hercules went among the cattle of Augeas, he wore his lion's skin as usual. The wind brought the scent of the skin to Phaethon, who, connecting that scent with the worst of the enemies from which it was his duty to defend the herd, came rushing up to attack Hercules. But Hercules, being so exceedingly strong, had no fear of the bull; he simply caught him by one white horn, turned his head and bent it to the ground, showing himself to be the master. After this, whenever Hercules came near, Phaethon stood off respectfully, and the other cattle followed his example.

The stables of Augeas stood in a long line, close to the bank of a river. Hercules made quick work of this labor, for since the stables must be cleaned in one day, he dug a trench and turned the river through them. Numerous as the stables were, the running water soon swept them clean.

The Seventh Labor

The Capture of the Cretan Bull

W

HEN

Minos was chosen king of Crete, he wished to begin his reign by offering a sacrifice to Jupiter. Accordingly, he went down to the seashore, and built an altar of rough stones. Then he called on the sea-god, Neptune, asking him to send an animal for the sacrifice. He had scarcely expressed this desire, before there rose up out of the sea, a snow-white bull with silvery horns. There could not have been a more beautiful animal, or one more perfect for a sacrifice; but Minos thought it a pity that he could not keep such a superb creature, and when he found that it was gentle, as well as perfect in every other respect, instead of sacrificing it on the altar that he had built, he led it to the pasture where his own herd were feeding, and let it go.

This was wrong, because Neptune had sent the bull to be sacrificed to Jupiter, and for no other purpose. Therefore, the gods caused the beautiful creature to lose its gentle disposition, and to become wild and dangerous. It roamed through the woods of Crete, and was a terror to every one who lived on that island.

At last, King Eurystheus sent Hercules, for his seventh labor, to capture this Cretan bull.

Armed only with his club, Hercules went into a wood where the bull had been oftenest seen, and waited by a spring. Soon he heard a hoarse bellowing, and caught a glimpse of something white, through the trees. A moment later, he saw the animal coming up to attack him and tossing its white horns fiercely. Throwing his club to the ground, he caught the bull by the horns, and held it firmly, in spite of its struggles, for he was the stronger of the two.

When the bull saw that it had found its master, its former gentle disposition returned to it, and it forgot all its wild ways, and followed Hercules about as if it had been a pet lamb. Afterward, in taking it to Mycenæ, Hercules let it swim across the sea, while he rode on its back.

The Eighth Labor

The Capture of the Horses of Diomedes

D

IOMEDES,

a king of Thrace, was a fierce, war-loving monarch, who was said to be a son of Mars. He had no regard for the laws of hospitality. When people were wrecked on his coasts, they were seldom heard from again.

He had a pair of war-horses, so vicious and dangerous that they had to be fastened with chains. It was whispered that the reason why the horses of Diomedes were so very dangerous was that they were fed on human flesh; and furthermore, that this explained the complete disappearance of all who had been wrecked on the coasts of King Diomedes.

King Eurystheus sent Hercules to bring the horses of Diomedes to Mycenæ, and as usual, to make the task harder, he desired him to bring them alive.

Hercules went to the country of Diomedes, and here he soon found that the dreadful reports he had heard about this ruler were all true. He went straight to the king's stables, and easily overpowered the guards. Then he unfastened the horses, fierce as they were, and led them by their chains to the shore. But here he was overtaken by a crowd of angry men, all calling upon him to stop.

He soon found himself fighting with King Diomedes himself. This strange king liked nothing better than fighting, and fully intended that Hercules should furnish a meal for his horses. But Hercules soon overpowered the king and made him a prisoner, thus putting an end to his cruelty.

Then Hercules took the horses to Mycenæ, and presented them to King Eurystheus, who doubtless was delighted at receiving such a valuable present. The horses soon escaped from his stables, and ran wild in the Arcadian hills, where they were finally eaten by wolves.

The Ninth Labor

The Securing of the Girdle of Hippolyte

S

OON

after the capture of the horses of Diomedes, Hercules was sent to the country of the Amazons to get Queen Hippolyte's girdle.

The Amazons were a race of women who delighted in warfare and hunting. They lived at some distance from Greece, on the Caucasus Mountains and on the borders of the Black Sea. Their queen, Hippolyte, had a very famous girdle, which was a gift to her from Mars, the war-god. It was said to be some magic power in this girdle which made the onslaught of the Amazons so like a rushing, irresistible storm. The Greeks, in their wars, had more than once found themselves opposed to the Amazons, and knew them for a formidable enemy.

AMAZON

The daughter of Eurystheus, who was a priestess, thought that Hercules could not do a better service for the Greeks than to secure this girdle of Queen Hippolyte. So Eurystheus sent him for it.

Hercules, therefore, crossed the Black Sea, and went to the country of the Amazons. He anchored his ship in the harbor, not far from the queen's palace, and Queen Hippolyte and some of her women went on board, to see who had come among them. The queen, who was brave herself, and admired courage in others, welcomed the famous Hercules in a kindly manner, and gave him the girdle. But one of the Amazons, seeing the queen on board the ship, raised the cry that a stranger was carrying off Queen Hippolyte by force. The Amazons then armed themselves and flew toward the ship from all directions. In spite of this, Hercules escaped with the girdle,—although not without fighting,—and was soon crossing the Black Sea on his way home.

When he reached Mycenæ, he presented the famous girdle, which was set with precious stones and heavy with gold, to the daughter of King Eurystheus. So ended his ninth labor.

The Tenth Labor

The Fetching of the Cattle of Geryon

Y

OU

would think that all the monsters in the neighborhood of Mycenæ must have been slain by this time, and all the near-by kings and queens who were enemies of King Eurystheus, overcome. In fact, Eurystheus did find it necessary to send Hercules a long distance from Mycenæ, next time; for he ordered him to go to an island that lay just beyond the country where the sun sets, and bring back the red cattle of the giant, Geryon.

This Geryon was a most extraordinary giant. He had three bodies, three heads, six legs, and six arms, besides a pair of wings. He had an enormous herd of cattle, which he kept, at night, in a dark cave.

To aid him in this tenth labor, Hercules borrowed the golden cup in which the sun-god, Helios, was borne round the world, from west to east, every night. This cup would float on the water like a boat, and had the remarkable power of becoming larger or smaller, according to the needs of the person using it. In it Hercules was carried straight west for a long time—farther west than any one had ever gone before.

Oceanus, the god of the ocean, was angry at having his dominions invaded, and raised a great storm. The golden cup was caught in a whirling cloud of spray, and tossed up and down as if it had been a bubble. But Hercules, nothing daunted, aimed one of his arrows at Oceanus, who laughed heartily at this impertinence, and then quieted the waters.

When Hercules reached the island, he climbed a high mountain, in order that he might look out over all the land, and see where the cattle of Geryon were grazing. As he stood there he was attacked by Geryon's savage two-headed dog. He killed the beast with his club, but hardly had time to draw a long breath before he was attacked by Geryon's herdsman, who was quite as savage as the dog, and would gladly have torn Hercules limb from limb. With a single blow from his ponderous club, he killed the herdsman also.

Then he saw the cattle grazing in a meadow, and began to drive them away. By this time Geryon himself had seen him, and came striding toward him swinging six clubs at a time with his six hands, and bellowing threats of death and destruction from all three of his huge throats at once. He looked like an animated windmill as he came down the hill, and would have frightened most people out of their wits. But Hercules remembered his poisoned arrows, and he sent a shaft so straight, that it made an end of the giant before he came near enough to do any harm.

Then Hercules gathered the cattle together and drove them into the cup of Helios, in which he transported them to the mainland. Afterward, some of them died, having been attacked by enormous swarms of flies; and others were lost through meeting with robbers and giants, but he succeeded in driving the remainder all the way to Mycenæ.

The Eleventh Labor

The Procuring of the Golden Apples

A

FTER

Hercules brought the cattle of Geryon to Mycenæ, King Eurystheus, wishing the hero farther away than ever, sent him once more to the country beyond the sunset. This time the king's excuse was, that he wished to have three of the golden apples which grew in the Garden of the Hesperides.

Although all had heard of this famous garden, no one at Mycenæ could tell Hercules where to find it. Some said it was far to the north, others that it was far to the west.

So Hercules started out, and walked in a north-westerly direction, till he reached the river Rhone.