Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) (19 page)

Read Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Lilian Stoughton Hyde

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

I

N

a certain pleasant valley, surrounded by low mountains, there was once a very wicked village. Strangers who had passed through this village on their travels complained bitterly of the inhabitants. They said that as they passed along the road, if they were tired and hungry, and looked at the open doors of the houses, hoping for hospitality, it was only to see the doors slammed in their faces, and to hear the grinding of bolts. Not only this, but they had been stoned and ill-treated in every possible way. It was no wonder that the news of these things reached the gods of Olympus.

One day two strangers, who were somewhat different from travellers in general, passed through the place. It was almost dark, and the night air felt sharp and frosty. The strangers knocked at door after door, without finding any one who was willing to admit them, till they had tried every house but one in the village.

The last house of all stood out a little beyond the others, on the edge of a great swamp. It was a small cottage with only two rooms, and the roof was thatched with straw and with reeds from the swamp. Here lived two old people, Philemon and Baucis.

This old couple, who were not at all like the rest of the people in the village, would never have thought of throwing stones at strangers, of setting dogs on them, or of bolting their doors when they saw them coming. Instead of doing any of these things, they opened their doors, and invited the two strangers to come in.

The door of this modest little cottage was so low that the taller of the two strangers had to bend his head as he entered. Inside, the two rooms were almost bare of furniture. But Philemon and Baucis, poor as they were, made the strangers welcome to the best of all they had.

Baucis drew the ashes from the fire, which had been kept from the day before, brought in fagots, and soon had them crackling under a small kettle. While the water was heating, she brought vegetables from her little garden, and sat down to strip off the leaves.

Meanwhile, Philemon lifted down a side of bacon which hung on a beam overhead, and cut off a piece for Baucis to cook.

Then Baucis brought out a rickety table, blocked up one of the legs to make it stand level, and polished it off with a handful of fragrant mint. Next she placed upon the table a few figs that had grown in her own garden, a brown loaf, and a bottle of home-made wine, still sweet. When the bacon and the vegetables were done, she roasted some fresh eggs in the embers. The dinner was now ready, and the strangers were invited to seat themselves at the table.

If Philemon and Baucis had been alone, their dinner would have consisted of nothing more than the brown bread and the home-made wine, with perhaps a small scrap of bacon. But Baucis thought that the strangers must be tired and hungry, and besides, it seemed to her that it was her duty to show these chance guests such hospitality as her small means would allow.

YOUTHFUL BACCHUS

Almost at the beginning of the meal a very strange thing happened. The cup of sweet wine, as it was passed round the table from one to another, was always full to the brim, no matter how much had just been drunk.

When Philemon and Baucis saw this, they were frightened. They had heard of such things happening, when people had been entertaining the gods, unawares. Looking at their guests more closely, they saw that the taller one certainly had a majestic air. The other had a face whose expression was constantly changing, and there was a look of mischief in his bright eyes.

The first thought of both of the old people, now, was that they had not done enough for such guests. Baucis jumped up from her chair, and ran out to catch the goose—the only thing that she and Philemon had left—intending to cook that, too. Philemon tried to help her, but neither of the old people could see very well, and they could not catch the goose. It raised its great white wings, and ran hither and thither. At last it ran into the cottage and straight up to the two strange guests, who said it should not be killed.

Then the guests told Philemon and Baucis who they were, and why they had come to the village. It was Jupiter and Mercury. They had heard the complaints of the travellers who had been so badly used, and had come to see whether the people of that village really were as wicked as they had been reported to be. They had found it all too true, and now, they said, these people must be punished.

Then they told the old couple, who had taken no share in the wickedness of the other villagers, to follow them up the mountain-side. There was a full moon, and Philemon and Baucis could see almost as clearly as their old eyes would let them see in the daytime. When they had nearly reached the top of the mountain, Jupiter told them to turn and look back at the village. The houses were slowly sinking out of sight, and presently a lake took their place, and looked as peaceful in the moonlight as if no village had ever been there. Not one of the village people was ever seen again.

Then a change came over the house of Philemon and Baucis. The thatched roof began to look yellow, like gold, while the sides grew white, and it became a marble temple, with a golden roof.

Jupiter told Philemon and Baucis to wish for whatever they liked, and their wish should be granted. The two old people could think of nothing better than that they might die at exactly the same moment, so that neither one should be left to mourn the other. Jupiter and Mercury then vanished and the old people went back down the mountain, and became priest and priestess in the temple, where they lived happily for many years.

One morning early, a long, long time afterward, some peasants came up to the temple with a present of new-laid eggs for the old priest and priestess. On coming near the temple what was their astonishment to see two grand old trees, an oak and a lime, standing just in front of the temple doors, where no tree had ever stood before. This was a marvel to them. When they came to look for Philemon and Baucis, they could not find them, and the two old people were never seen in that country again. But the two trees stood there for many, many centuries, even after the temple had grown old and fallen to ruin. Travellers who rested in their hospitable shade, used to tell each other the story of the wicked villagers, and of Philemon and Baucis.

O

RPHEUS,

the son of Apollo, was a wonderful musician. He had a lyre of his own, and learned to play on it, when he was very young. This lyre was not quite so fine a one, perhaps, as Apollo's famous golden lyre, but it could produce marvellous music.

Orpheus often went to a lonely place, outside the village, where he would sit on the rocks and play all day long. Then the spiders stopped their spinning, the ants left off running to and fro, and the bees forgot to gather honey; for none of them had ever heard such sweet music before. The little birds who had their nests in the grass did not know what new singer had come among them. They gathered around Orpheus to listen, some hopping around on the rocks, and others swinging on tall weeds, and trying to catch the tune.

One day a cobra, gliding by slyly under the grass-heads, in the hope of finding eggs or young birds in some ground-nest, heard the music, and stopped to listen. He coiled himself up, raised his head, and swayed back and forth, in time to the music. The birds had nothing to fear from him while such music was filling the air. But they knew him well, as he lived close by under a rock.

As Orpheus grew older, his music became more and more wonderful. When he went to the old place to play, all the animals and birds in the fields and in the forest gathered around him. Lions, bears, wolves, foxes, eagles, hawks, owls, squirrels, little field-mice, and many other kinds of creatures were in the audience. Even the trees in the grove, near by, tore themselves up by the roots, and came and stood in the circle around Orpheus, so that they could hear better. Their branches cast a pleasant shade over the other listeners, and over Orpheus, as well, keeping off the hot rays of the afternoon sun.

The nymphs of the valley soon made friends with Orpheus, and when he had grown to be a man, one of them, whose name was Eurydice, became his wife.

One day, as Eurydice was running carelessly through the meadows, she stepped on the cobra that lived under the rock. Although the cobra was always gentle when under the influence of the magical music of Orpheus, he was not so at other times. He turned, instantly, and bit Eurydice on the ankle.

Then Eurydice had to go down to the dark underworld, where Pluto was king, and Proserpine queen.

When Orpheus came back to the meadows, he could not find Eurydice. He took his lyre, and played his sweetest, most entrancing strains, while he wandered all about the mountains and valleys, calling to her. Her sister nymphs joined him in the search, and everywhere the hills echoed their calls of "Eurydice, Eurydice!" but there was no answer.

Orpheus could not bear to give up Eurydice for lost. After he had looked everywhere on earth, without finding her, he knew that she must be in the underworld. He made up his mind that he would go down and play before King Pluto. He thought perhaps he could persuade Pluto and Proserpine to let her come back to the sunny valley again.

So he went down into Pluto's kingdom, and there he played such a very sweet, sad song that tears came into the eyes of all who heard it. Even Pluto, whom men thought very hard-hearted, could not help feeling sorry for the singer.

When the song was over, Orpheus implored that Eurydice might be allowed to return with him to the upper world, saying that he could not return without her. Pluto consented to let her go on one condition, and that condition was, that Orpheus must have faith to believe that Eurydice was following him, and until he reached the upper air, must not look back to see.

So Orpheus started back again, playing softly on his lyre. The music was not sad now. You would have thought that the dawn was coming, and that young birds were just waking in their nests. In the darkness, for it is always dark in the underworld, Eurydice was following; but Orpheus could not be sure of this. He slowly climbed the steep path over the rocks, back to the world of light and warmth. Just as he had almost reached that familiar world; just as he could feel the fresh air from the sea on his forehead, and could see the glimmer of a sunbeam reflected on the rocks, he felt all at once as if Eurydice were not there. The thought flashed into his mind that King Pluto might be deceiving him. He turned his head, and by the dim light which was beginning to break over his path, saw Eurydice fading away and sinking down into the underworld. Her arms were stretched out toward him, but she could not follow him any farther. He had broken the condition imposed by Pluto, hence Eurydice must go back among the shades.

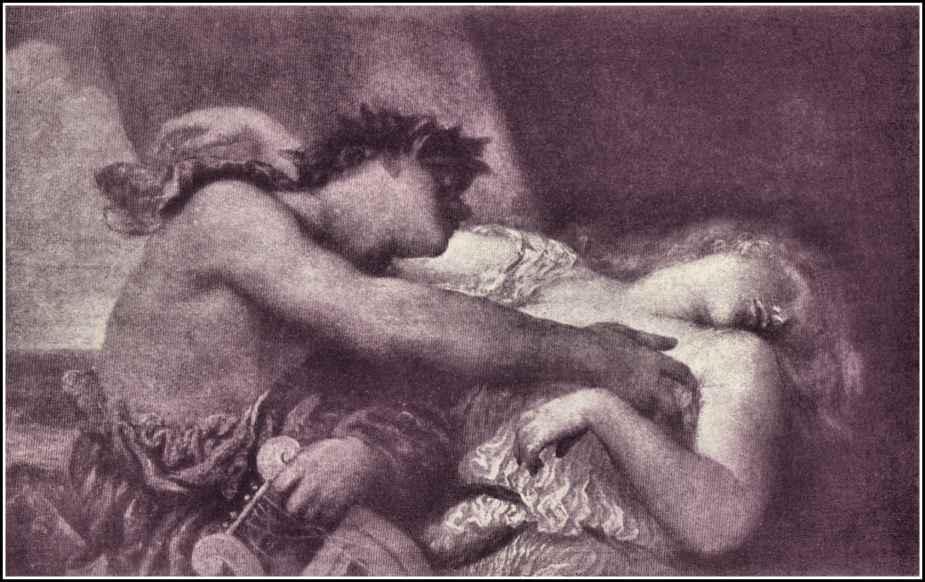

ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE

Oh, if only he had not looked back! Eurydice was lost indeed now. Orpheus knew that it would be of no use to try again to bring her to the upper world. He did not go back to the pleasant valley in which he had grown up, but went to live on a lonely mountain, where he spent all his days in grieving for Eurydice.