Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) (13 page)

Read Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Lilian Stoughton Hyde

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

When bright Adonis went down to the dark underworld, all things on earth mourned for him. The flowers faded in the fields, the trees cast down their leaves, the dolphins wept near the shore, and the nightingales sang the saddest songs they knew. The Muses cried, "Woe, woe for Adonis! He hath perished, the lovely Adonis!" And Echo, from the dark forests where the youth had so often hunted, answered, "He hath perished, the lovely Adonis!"

At last Jupiter said that Adonis should return, and that he should spend at least one-half of his time in the upper world and the other half in the underworld. So the Hours brought him back.

Then the flowers sprang up again, the trees put forth new leaves, and all became light-hearted and happy once more.

King Midas and the Golden Touch

I

T

happened one day that Silenus, who was the oldest of the satyrs and was now very feeble, became lost in the vineyards of King Midas. The peasants found him wandering helplessly about, scarcely able to walk, and brought him to the king.

Long ago, when the mother of Bacchus had died, and when Mercury had brought the infant Bacchus to this mountain and put him in the care of the nymphs, Silenus had acted as nurse and teacher to the little wine-god. Now that Silenus had grown old, Bacchus in turn took care of him. So King Midas sent the peasants to carry the satyr safely to Bacchus.

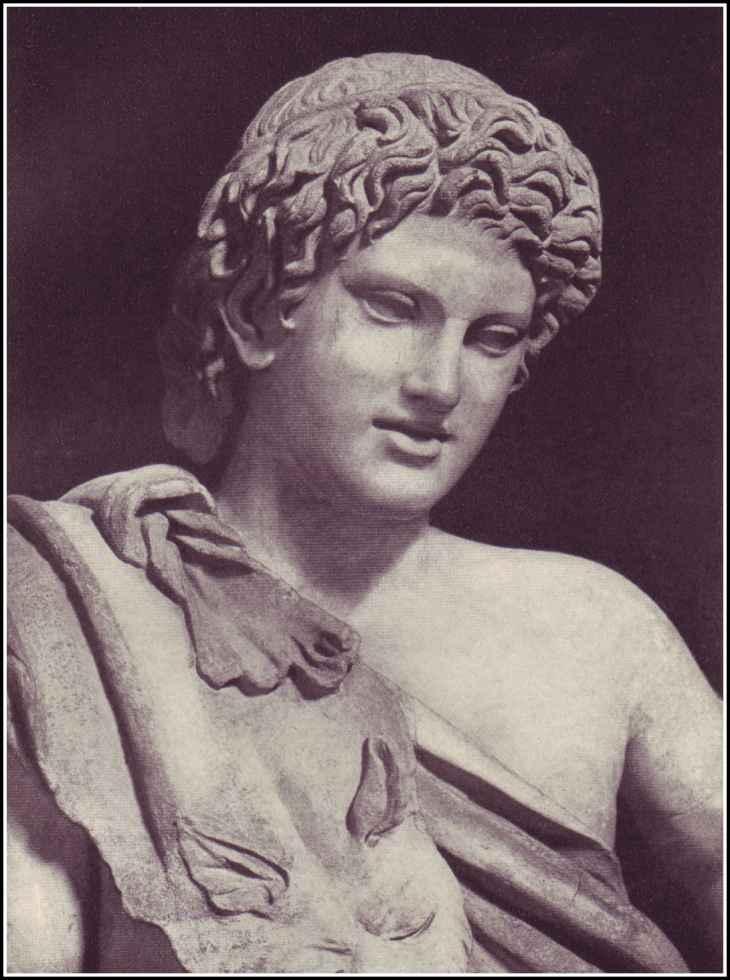

YOUTHFUL BACCHUS

In return for this kindness, Bacchus promised to grant whatever King Midas might ask. King Midas knew well enough what he most desired. In those days, kings had treasuries in their palaces, that is, safe places where they could lay away valuable things. The treasury of King Midas contained a vast collection of rich jewels, vessels of silver and gold, chests of gold coins, and other things that he considered precious.

When Midas was a very little child, he used to watch the ants running back and forth over the sand near his father's palace. It seemed to him that the ant-hill was like another palace, and that the ants were working very hard carrying in treasure; for they came running to the ant-hill from all directions, carrying little white bundles. Midas made up his mind, then, that when he grew up, he would work very hard and gather treasure together.

Now that he was a man, and the king, nothing gave him more pleasure than to add to the collection in his treasury. He was continually devising ways of exchanging or selling various things, or contriving some new tax for the people to pay, and turning all into gold or silver. In fact, he had gathered treasure together so industriously, and for so many years, that he had begun to think that the bright yellow gold in his chests was the most beautiful and the most precious thing in the world.

So when Bacchus offered him anything that he might ask for, King Midas's first thought was of his treasury, and he asked that whatever he touched might be turned into gold. His wish was granted.

King Midas was hardly able to believe in his good fortune. He thought himself the luckiest of men.

At the time his wish was granted he happened to stand under an oak tree, and the first thing he did was to raise his hand and touch one of its branches. Immediately the branch became the richest gold, with all the little acorns as perfect as ever. He laughed triumphantly at that, and then he touched a small stone, which lay on the ground. This became a solid gold nugget. Then he picked an apple from a tree, and held a beautiful, bright, gold apple in his hand. Oh, there was no doubt about it. King Midas really had the Golden Touch! He thought it too good to be true. After this he touched the lilies that bordered the walk. They turned from pure white to bright yellow, but bent their heads lower than ever, as if they were ashamed of the change that the touch of King Midas had wrought in them.

Before turning any more things into gold, the king sat down at the little table which his slaves had brought out into the court. The parched corn was fresh and crisp, and the grapes juicy and sweet. But when he tasted a grape from one of the luscious clusters, it became a hard ball of gold in his mouth. This was very unpleasant. He laid the gold ball on the table and tried the parched wheat, but only to have his mouth filled with hard yellow metal. Feeling as if he were choking, he took a sip of water, and at the touch of his lips even this became liquid gold.

Then all his bright treasures began to look ugly to him, and his heart grew as heavy as if that, too, were turning to gold.

That night King Midas lay down under a gorgeous golden counterpane, with his head upon a pillow of solid gold; but he could not rest, sleep would not come to him. As he lay there, he began to fear that his queen, his little children, and all his kind friends, might be changed to hard, golden statues.

This would be more deplorable than anything else that had resulted from his foolish wish. Poor Midas saw now that riches were not the most desirable of all things. He was cured forever of his love of gold. The instant it was daylight he rushed to Bacchus, and implored the god to take back his fatal gift.

"Ah," said Bacchus, smiling, "so you have gold enough, at last. Very well. If you are sure that you do not wish to change anything more into that metal, go and bathe in the spring where the river Pactolus rises. The pure water of that spring will wash away the Golden Touch."

King Midas gladly obeyed, and became as free from the Golden Touch as when he was a boy watching the ants. But the strange magic was imparted to the waters of the spring, and to this day the river Pactolus has golden sands.

Why King Midas Had Asses' Ears

A

FTER

his strange experience with the Golden Touch, King Midas did not care for the things in his treasure chests any more, but left them to the dust and the spiders, and went out into the fields, and followed Pan.

Pan was the god of the flocks, the friend of shepherds and country folk. He lived in a cave, which was in a mountain not far from the palace of Midas. He was sometimes seen, playing on his pipe, or dancing with the forest nymphs. He had horns and legs like a goat, and furry, pointed ears.

HEAD OF FAUN

Pan was a sunny, careless, happy-go-lucky kind of god, and when he sat playing on his pipe—which he himself had made—the music came bubbling forth in such a jolly way that it set the nymphs to dancing, and the birds to singing.

When King Midas heard Pan's pipe, he used to forget that he was a king, or that he had any cares whatever. He was content to feel the warmth of the sun, and breathe the sweet air of the mountain.

One day Pan boasted to the nymphs, in a joking way, that the music of his pipe was better than that of Apollo's lyre. The nymphs laughed, and said that he and Apollo ought to play together, with Tmolus, the god of the mountain, for the judge. Pan said that he was ready to try his skill against Apollo's. Tmolus consented to be the judge. So a day was appointed for the contest.

Apollo came with his lyre. He had a laurel crown on his head, and wore a rich purple robe which swept the ground. His lyre, which was a beautiful instrument, was made of gold, and was inlaid with ivory and precious stones. This made Pan's pipe, which consisted of seven pieces of a hollow reed lightly joined together, look very simple and rustic.

Both Apollo and Pan began to play. Tmolus turned toward Apollo, to listen, and all his trees turned with him. Before they had played long, the mountain-god stopped Pan, saying, "You must know that your simple pipe cannot compare with Apollo's wonderful lyre."

Pan took this in good part; he knew that the contest had been only a joke. While the nymphs and the shepherds made light of the decision against their friend, Midas, who could not appreciate the lyre, but who was just suited by the music of the pipe, jumped up and cried out, "This is unjust! Pan's music is better than that of Apollo!"

At this, all but Apollo laughed. He was angry. He looked severely at the ears of Midas, which must have heard so crudely. All at once King Midas felt his ears growing long and furry. He clapped his hands over them, and rushed to a spring near by, where he could see himself. His ears had been changed into those of an ass.

So Midas was punished by the gods a second time for his foolishness. He was very much ashamed of those long, furry ears, and always after that wore a great, purple turban to hide them.

One day, when the court-barber was cutting Midas's hair, he discovered the king's secret, and was so much astonished that he dropped his shears on the floor with a great clatter. He knew he might lose his head if he should tell what he had seen. So he said not a word to any mortal soul; but one day, to relieve his mind, he went to a lonely place, dug a hole in the ground, and whispered what he had seen to the earth. Then he put the soil back, and so buried the secret.

But after a secret has once been told, it is not so easy to hide it. After about a year, some reeds grew up in that place. When the south wind blew, they whispered together all day, and told one another that, under his turban, King Midas had asses' ears. And so the secret was spread abroad.

T

HERE

was once a beautiful grove, in Thessaly, which was sacred to Ceres. The trees in it had been growing there for nobody knows how many hundreds of years. They were very, very large, and their great branches grew so close together that scarcely a ray of sunshine could penetrate to the ground underneath.

It was cool in this grove, even on the hottest summer day. Little fawns and their mothers lay on the pine needles in the shade, feeling safer there than anywhere else. Birds sang from the tops of the tallest trees, and many a nest was hidden under their leaves.

The temple of the goddess stood in an open glade, in which were sparkling fountains, whose waters kept everything fresh and green. Here grew the grandest tree of all, a gigantic oak, so tall that its top seemed to reach almost to heaven. Its lower branches were thickly hung with wreaths, and votive tablets, on which were written the thanks of people who had received the help of Ceres.