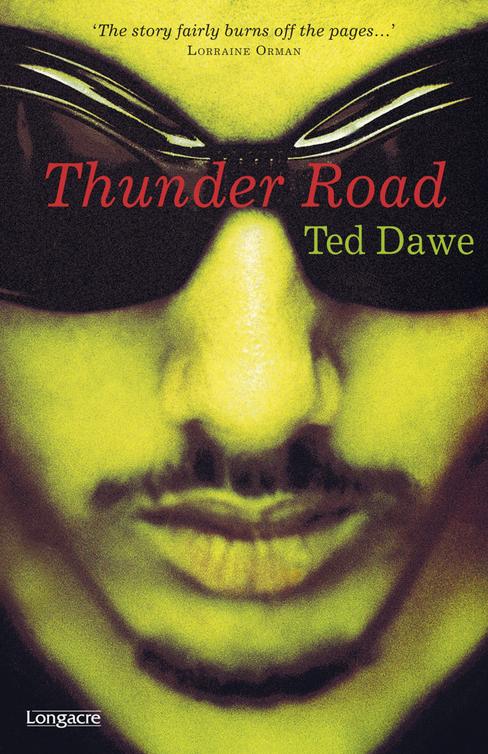

Thunder Road

Authors: Ted Dawe

Thunder Road

—

you find it in any city after dark. It’s where street racers go to test their machines — and their nerve.

Trace has grown out of small town ways. In the city he hooks up with Devon, a guy with the golden touch, who introduces Trace to burn-offs, big-city style.

When Trace falls for a girl even Devon says is out of his league, loyalties are stretched. Then Devon hits on a scheme for hauling in cash. Soon he and Trace find out who really controls Thunder Road. As trouble closes in, everyone is heading for burnout — fast.

A fast-paced, gripping novel from a remarkable talent.

‘Dawe doesn’t so much speak their language as take hold of it and turn it into a kind of poetry of the street…. half coming-of-age story, half thriller, this is an impressive debut.’

D

AVID

L

ARSEN

, NZ H

ERALD

Praise for

Thunder Road

‘The story fairly burns off the pages – older teenage boys will love it, adults will frown and talk about bad influences, so be warned.’ L

ORRAINE

O

RMAN

‘It’s a novel that revs and snarls, and never loses traction. …confronts the reader with the powerful and sometimes inexplicable impulses of youth…’ F

ROM

JUDGES

’

REPORT

, NZ P

OST

C

HILDREN’S

B

OOK

A

WARDS

‘This isn’t just a book about fast cars, danger and proving oneself, it’s about love, really, and loyalty…’ C

ASS

A

LEXANDER

,

Salient

‘I confidently predict that this novel will become the most stolen book in school libraries.’

English in Australia

‘You’ll be sucked into a world of menace, treachery and danger. Fabulous!’ B

EN

T

HORPE

, Y

EAR

9,

Around the Bookshops

‘…a riveting novel that this reviewer read in one sitting. …clever, witty and a thoroughly good read.’

Viewpoint

‘…glories in and vilifies the street-racing culture. A sobering and street-savvy revelation.’

North & South

Ted Dawe

This book is dedicated to the memory of four people.

To my cousin, Jak D’Ath, who rides beside me always.

To my grandmother, Rewa D’Ath, who taught me what love is.

To my friend, Dora Ridall, who never doubted me.

To my Rangatira, Niko Tangaroa.

Ki a koe toku Rangatira kua wheturangatia Nau te Kākano nei I Whakaawe

No reira Haere Haere Haere atu ra.

To you, my chief, among the Stars and Heavens You have inspired me, I am now the seed.

Farewell Farewell Farewell.

To Jane McKay, whose belief and enthusiasm drove me on.

To Bernard McKissock-Davis, Ross Browne, Sion McKay and David Blaker who laboured through my earlier attempts.

To Neville Byrt and Julia Brown who helped polish my later ones.

To Tipene Pai who checked te reo. Kia ora e hoa.

To the boys at Dilworth School who road-tested this beast and gave it the thumbs up.

To Barbara Larson and all her staff at Longacre Press who

embraced

this project so enthusiastically.

To Emma Neale, whose sensitivity and erudition had so much to do with how this book reads today.

To Professor J M Coetzee for his time, grace and advice.

To you all, my deeply felt thanks and appreciation.

The highway’s jammed with broken heroes On a last chance power drive Everybody’s on the run tonight But there’s no place left to hide

From ‘Born to Run’ Bruce Springsteen

I’m no writer. I’ll tell you that for nothing.

I just thought, it’s me who should set the record straight, so here I am doing it now.

Doing it for Devon.

Where to start?

I was born. No, what the hell does that matter?

My parents?

Ahh, forget it. No need to go that far back.

When I was little my father used to say, ‘Trace, there is a right and a wrong way of doing anything’.

I could live with that.

When I was about 13 or 14 it had changed to ‘Trace, there’s my way, and the wrong way’.

I couldn’t live with that.

So when I was 15 I shot through.

I’ve done a lot of dumb things between then and now, but leaving home wasn’t one of them.

I reckon you’ve got to know when to stay and fight and when to walk away.

As a kid I would lie in bed and listen to the cars gunning it down Dyson Road. I knew each car, its make and who owned it from the exhaust note. Such sweet sounds! My mates were all into heavy metal music, dope or rugby. For me it was an engine begging for mercy (there is no mercy), the steep rising pitch of the turbo, the screaming tyres and the curtain

of white smoke hanging behind me: all the stuff that spells street racing. Nothing compared to that. Anything else was second best.

We were partners, Devon and me. All this stuff I’m going to tell you took place when I first came to Auckland. So much has happened. It’s like it was a lifetime ago and just yesterday at the same time. It takes me a while so you’re going to have to be patient. There’s so much to tell.

AFTER A COUPLE of years working as a plumber’s mate on a building site, I knew that it was time to look for something else. The guys I worked with, Jesus, they looked beaten. As though life had already ripped them off. Each day, Wally, my boss, would fill his lunch box with flattened out copper pipe, smuggling it home to sell on.

‘I’ve got nearly a hundred kilos in the garage.’

One afternoon the crane broke down and couldn’t be fixed for four days. A load of heater pipes arrived that were needed on the fourth floor. Me and Patrick, being the only labourers on the site, were told to carry them up. The plumbers and the fitters wouldn’t touch them. Patrick stood next to the pipes, pondering his next move. He was over 50 years old and there were limits to what he would and wouldn’t do. After a spell in the site office he disappeared out the back. I waited by the pipes, wondering what would happen next.

After a while, Eric, the site foreman, came out. He paused in the doorway for a moment to light his pipe. He looked

awkward

. I knew what he was going to say before he opened his mouth.

‘Patrick has some holes to drill so I guess it’s going to be you laddie. Best to carry them up the stairwell.’

I was so pissed. The unfairness of it. The youngest gets the shit job.

‘Can’t be done, Eric, it’s a two-man job.’

‘No, it’s just a slow job, that’s all laddie.’

‘That’ll take days.’

‘That’s what you’re paid for, lad.’

‘To do the work of a crane?’

He closed in on me. ‘To do what ever fucking jobs need to be done. So get started, eh?’

As I hauled a pipe up to the third floor, I could hear the voices of the men mimicking Eric’s Geordie accent.

‘So get started, laddie.’

‘Upwards and onwards.’

‘Don’t make a fuss, lad, we need those pipes.’

I smouldered away angrily to myself. The injustice. There were limits. Just because I was the labourer didn’t mean that I had to do anything they said. That was slavery.

I walked to the window and looked out across the scaffolding. There was Patrick, de-nailing some timber on the far side of the yard. The work given out only when there was nothing else to do. I climbed out and sat down on the planks, feet dangling. I didn’t know what to do next, or what was going to happen, so I pulled out my smokes and waited.

Sure enough, before long Eric emerged from the site office and looked up at me. He waved his arm angrily. I waved back.

‘Get on with it, laddie.’

His voice sounded weak from this distance. I didn’t respond. He strode purposefully across the yard towards the bottom of the building.

‘Get on with it, Trace,’ one of the plumbers called out, only half joking this time.

I could sense a back-down of sorts. I stood up and looked at the three men in the gloom of the building. There was

something a bit hesitant about them this time, like schoolboys crumbling under a challenge.

‘Fuck you too,’ I said. They weren’t my mates.

Eric arrived.

‘Too good for this sort of work, lad?’

‘I’m not doing it.’

‘Two choices, lad. Think carefully.’

‘Do it yourself, Eric.’

‘Pack up. You’re out of here.’

‘So that’s it?’

‘Seems so,’ he said as he walked off.

There’s always a moment when decisions have to be made. This was one of them.

We were just coming out of winter; the last three months were the coldest I could remember. Every morning, at seven, chipping away in the gloom with a cold chisel, the afternoons spent waiting for the five o’clock whistle … I guess all they wanted was my obedience, so when I wouldn’t carry those pipes, something else was made clear to me.

‘You’re off? Fine, we’ll replace you tomorrow.’

Which is another way of saying, ‘You’re shit. See ya.’

I’d had enough of small town life, so I set off for the smoke. I’m one of those guys who sees everything that happens as an opportunity. This was an opportunity to get the hell out of the whole hometown/family scene at the same time.

I got this real buzz of freedom as I stuck my thumb out on Highway One and an even better one when I heard the gasp of airbrakes. A big furniture truck. He was going all the way to Auckland so it was like I was there already.

The truckie put me onto a room in this big old house run by a woman called Mrs Jacques. As it happened she had a spot, a room share, cheap as, in the front overlooking a busy road. Cars hooning up and down all day. Ideal.

Mrs Jacques was in her late fifties and had the battered look of an over-ripe peach. The sort that are marked down in special trays out the front of the fruiterer’s. She had known tragedy and wasn’t afraid to talk about it. In half an hour I had her life story. An hour after that I had forgotten most of it. She took pains to spell out that she ran a tight ship, her husband, ‘bless his soul’, had been in the navy. That she would ‘brook no

jiggery

pokery’.

There were two other guys living there. I shared a room with Devon; he was out of town at the time, so I had it to myself for a couple of days. I could tell from the things scattered around he was into the same sort of stuff as me. Car stuff, brand badges, posters, books and mags. A few porn type mags, too, in among everything else.

There was a framed picture on the chest of drawers: this

really

pretty girl sitting on the bonnet of an Escort. It had been taken at some beach. A pair of sunglasses and a bottle of beer that I guess he had put down to take the photo, waited on the roof. There weren’t many clothes in the room, but there were cartons of junk under the bed and an oily smell which made me think of engine parts.

The other guy, Sergei, was a music teacher. He gave piano lessons in the front room. Although he must have been over 30, his face was smooth and unlined like he had never been out in the sun. Maybe it was because he was a foreigner (he came from Poland) that everything about him seemed extreme: bushy beard, wild hair, staring eyes and this really dramatic

way of talking. Full of spit and hand movements. Whenever he spoke it was like he was making an announcement,

broadcasting

to the nation.

Mrs Jacques adored him. He was like a visiting celebrity, not a boarder – first class all the way for him. He was a big man with small hands and feet, narrow shoulders and wide hips. Too long sitting at a piano, I guess. He didn’t walk around the house, he surged from place to place. Like he was on wheels.

The large room across the hall from us was his: it was there that a procession of small kids, arriving by bike or being dropped off by waiting parents, received their weekly

instruction

on the ‘pianoforte’, as he called it.

I reckon Sergei had seen heaps of films about ‘The Great Composer’, the misunderstood genius. When we watched TV that first night he kept claiming to have written the theme music for this show or that ad: ‘Did you hear that, Mrs Jacques, that introduction … it was a steal from my theme music for… there is not an original composer in this entire country… a nation of stealers… plagiarists….’

It took a few days to get used to him. The bang of the piano lid was usually followed by Sergei bursting from his room, hand glued to his forehead, throwing himself into an armchair. Mrs Jacques would get really wound up.

‘What’s wrong Sergei? Is it not going well today?’ Trying to make him feel better. Terrified he might leave.

‘Don’t ask, Mrs Jacques. I don’t know how much more of this I can take. Every note I play seems flat and toneless. Music for a coffin.’

‘Creative work is the hardest work there is,’ she said.

‘All my energy is stolen by tuition, no wonder nothing I write these days is any good.’

Mrs Jacques hovered sympathetically; I tried to read the paper. It was sort of embarrassing.

‘Mediocrity! I’m surrounded by it. When I think of what I might be able to write, if I wasn’t driving talentless, unmotivated schoolboys towards some Grade Three pianoforte qualification.’ He paused, gathering steam. ‘Just so their shallow mums and dads can tell themselves that they are doing

the right thing

by their children. I would rather teach a dog how to knit.’

He leaned back in the armchair, eyes tightly closed for a while, then sprang up and surged back into his room where he attacked the piano so savagely I thought it might explode. I could see his face reflected in the hall mirror. Completely rapt. Eyes locked shut. Head rocking backwards and forwards, sometimes swooping low over the keys, other times facing up towards the ceiling as if trying to suck down the creative energy. It was better than TV.

We were an odd crew, but somehow we got by. Maybe because this was where I started out in the big city, I put up with all the crap that came along. I didn’t know any better in those days. I do now.