Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (12 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

6.

a history of other heart disease or heart operations, especially valve replacement

7.

a history of intravenous drug abuse, particularly for its association with tricuspid and pulmonary valve infection

8.

antibiotic allergies

9.

how the diagnosis was made – including the number of blood cultures and the use of transthoracic or transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE)

10.

management since admission to hospital, including the names of the antibiotics used, the duration of treatment and whether the possibility of valve replacement has been discussed

11.

a history of other major diseases, particularly those associated with immune suppression, such as renal transplantation or steroid use.

The examination

1.

Start by examining for the peripheral stigmata of endocarditis.

a.

Hands:

•

clubbing

•

splinter haemorrhages (

Fig 5.1

)

FIGURE 5.1

Splinter haemorrhages. M H Swartz. The skin.

Textbook of physical diagnosis: history and examination

.

Fig 8

. Saunders, Elsevier, 2009, with permission.

•

Osler’s nodes on the finger pulp (these are always painful and palpable, are probably an embolic phenomenon and are rare)

•

Janeway lesions (

non-tender

erythematous maculopapular lesions containing bacteria on the palms or pulps, which are rare).

b.

Eyes:

Roth’s spots in the fundus (

Fig 5.2

), conjunctival petechiae.

FIGURE 5.2

(a) Right fundus and (b) left fundus, showing multiple flame-shaped and blot hemorrhages in both eyes. Several hemorrhages are white centered, consistent with Roth spots. A retinal hemorrhage is centered on the fovea of each eye, accounting for the decreased visual acuity. S Nazir.

Journal of AAPOS

. 2008. 12(4):415-417. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismu, with permission.

c.

Abdomen:

splenomegaly (a late sign).

d.

Urine analysis

for haematuria and proteinuria.

e.

Neurological signs

of embolic disease.

f.

Joints

(occasionally resembles rheumatic fever pattern).

2.

Next examine the

heart

. Assess for predisposing cardiac lesions. These are, in order:

a.

acquired:

•

prosthetic valve (mechanical)

•

mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis

•

aortic stenosis

•

aortic regurgitation

•

prosthetic valve (tissue)

•

repaired mitral valve

•

mitral valve prolapse with mitral regurgitation.

b.

congenital:

•

bicuspid aortic valve

•

patent ductus arteriosus

•

ventricular septal defect

•

coarctation of the aorta.

Remember:

• an atrial septal defect of the secundum type is almost never affected

• 20% of endocarditis patients have no recognised underlying cardiac abnormality

• coronary stents and pacemaker leads do not appear to involve any risk of endocarditis.

3.

Examine for the signs of cardiac failure. Look for signs of a prosthetic valve and for scars that may be present from previous valvotomy or repair operations.

4.

Look for a source of infection and take the patient’s temperature.

Investigations

1.

Three to six blood cultures

(at least) over 24 hours (98% of culture-positive cases will give positive results in the first three bottles).

2.

Full blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

. Look for anaemia (normochromic, normocytic), neutrophilia, an elevated ESR, which may be >100 mm/h and a raised C-reactive protein (CRP) level. The ESR tends to remain elevated for months, even when treatment has been successful, but the CRP level falls quite quickly and may be useful for assessing the effectiveness of treatment.

3.

Renal function

. A freshly spun urine sample will often show red cell casts but is rarely assessed these days.

4.

Chest X-ray film

. Look for left or right ventricular hypertrophy, increased pulmonary artery markings, Kerley’s B lines, frank cardiac failure and valve calcification (lateral film). The onset of heart failure is a poor prognostic sign.

5.

ECG

. Atrial fibrillation in the elderly (particularly common) and conduction defects may occur, but are not specific.

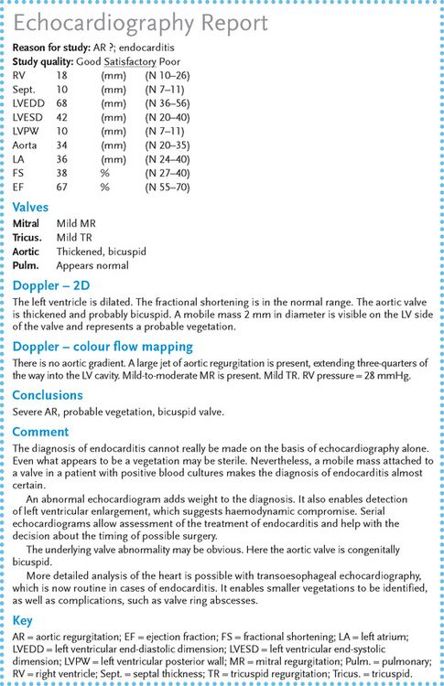

6.

Echocardiography

(

Fig 5.3

) (

2-D and Doppler

). Vegetations must be larger than 2 mm to be detected. This procedure cannot distinguish active from inactive lesions. Vegetations are seen in approximately 40% of cases. They tend to occur downstream of the abnormal jet, e.g. on the aortic surface of the aortic valve in cases of aortic stenosis and endocarditis. Colour Doppler examination is a very sensitive means of detecting new valvular regurgitation, which may be an important sign of endocarditis.

Transoesophageal echocardiography

allows better definition of valvular involvement and is more likely to detect vegetations. Perhaps more importantly, it is much more likely to detect such complications as valve abscesses. It is now in routine use for the assessment of endocarditis. Its use is routine in cases of known or suspected endocarditis.

FIGURE 5.3

Echocardiography report in a patient with possible infective endocarditis

7.

Serological tests

. These include tests for immune complexes and classical pathway activation of complement causing low C3, C4 and CH50 levels. The test for rheumatoid factor gives positive results in 50% of cases and that for antinuclear antibody in 20% of cases.

Notes

ORGANISMS

Streptococci account for approximately half of these infections.

1.

Streptococcus viridans

(non-haemolytic) – usually presents subacutely. The names of the viridans streptococci are subject to frequent revision but current important types for endocarditis include

S. sanguinis

,

S. gordonii

and

S. mitis

.

2.

Streptococcus faecalis

– traditionally more common in older men with prostatism and younger women with urinary tract infections, but now in intravenous drug users.

3.

Streptococcus bovis

– associated with colon polyps and carcinoma.

4.

Staphylococcus aureus

– particularly in drug addicts; usually presents acutely. Note, though, that only a small minority of

S. aureus

bacteraemias are associated with endocarditis.

5.

Staphylococcus epidermidis

– more common in patients with recent valve replacement but can be a contaminant in blood cultures.

6.

Gram-negative coccobacilli – rarely a cause; more common with prosthetic valves. The responsible organisms are called the HACEK group:

H

aemophilus

A

ctinobacillus

C

ariobacterium hominis

E

ikonella

spp.

K

ingella kingae

7.

Fungi (e.g.

Candida

,

Aspergillus

) – particularly in drug addicts and immuno-suppressed patients.

CAUSES OF CULTURE-NEGATIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Note:

This diagnosis should be made with caution. It condemns a patient to prolonged treatment with intravenous antibiotics.

1.

Previous use of antibiotics.

2.

Exotic organisms (e.g.

Haemophilus parainfluenzae

, histoplasmosis,

Brucella

,

Candida

, Q fever).

3.

Right-sided endocarditis (rarely).

POST-VALVE SURGERY ENDOCARDITIS

Early infection is acquired at operation; late infection occurs from another source. This condition has a worse prognosis than native valve endocarditis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually a clinical one. The Duke criteria are often used to assist. Two major criteria, one major and three minor, or five minor criteria secure the diagnosis.

MAJOR CRITERIA

1.

Typical organisms in two separate blood cultures.

2.

Evidence of endocardial involvement: echocardiogram showing a mobile intracardiac mass on a valve or in the path of a regurgitant jet, or an abscess or new valvular regurgitation.

MINOR CRITERIA

1.

Predisposing cardiac condition or intravenous drug use.

2.

Fever.

3.

Vascular phenomena or stigmata.

4.

Serological or acute phase abnormalities.

5.

Echocardiogram abnormal, but not meeting above criteria.

Treatment

Early involvement in the management by a cardiac surgeon in a cardiac surgical unit is usually indicated, particularly for staphylococcal infection.

1.

Intravenous administration of a bactericidal antibiotic. If the organism is a sensitive

S. viridans

, give benzylpenicillin, 6–12 g daily for 4–6 weeks. If it is an enterococcus, at least 4 weeks of intravenous treatment is necessary and the choice of antibiotic depends on the organism’s sensitivity. For prosthetic valves, 6–8 weeks of intravenous treatment is necessary.

2.

Follow the progress by looking at the temperature chart, serological results and haemoglobin values.

3.

The decision to go on to valve replacement is a difficult one; it is best made with the assistance of a cardiac surgeon who has been involved from the start. Indications for surgery include:

a.

resistant organisms (e.g. fungi)

b.

valvular dysfunction causing moderate-to-severe cardiac failure (e.g. acute severe aortic regurgitation)