Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (63 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

c.

episodes of visual disturbance – loss of acuity, pain on eye movement, loss of central visual field (optic neuritis), diplopia on lateral gaze

d.

episodes of ataxia, dysarthria and tremor – Charcot’s triad (owing to cerebellar or posterior column involvement)

e.

band sensations around trunk or limbs

f.

less common symptoms, such as vertigo, symptoms of cranial nerve disorders (e.g. tic douloureux), urinary urgency, incontinence of faeces, impotence, depression, euphoria, dementia, seizures, bulbar dysfunction (pseudobulbar palsy).

2.

Ask about precipitating factors, such as heat (hot baths, etc.), infection, fever, pregnancy and exercise. Disease activity tends to be less during pregnancy; relapse is common post-partum.

3.

Ask about family history: MS is seven times more common in immediate relatives (sibling risk is 5%).

4.

Ask about social disability – sexual function, ability to work, financial problems.

5.

Ask about place of birth: MS is more common in subjects who spent their childhood in temperate latitudes than in tropical regions. Smoking is also a risk factor.

6.

Find out what treatments have been tried and with what success and side-effects. Various unproven treatments are often tried by patients with this incurable disease. Ask whether any of these have been used.

The examination

1.

The signs can be very variable. Look particularly for signs of spastic paraparesis and posterior column sensory loss, as well as cerebellar signs.

2.

Examine the cranial nerves. Look carefully for loss of visual acuity, optic atrophy, papillitis and scotomata (usually central). Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is an important sign and is almost diagnostic in a young adult. It can also occur in patients with SLE or Sjögren’s syndrome who may have disease confined to the CNS, or with brain stem tumours or infarcts. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is weakness of adduction in one eye as a result of damage to the ipsilateral medial longitudinal fasciculus; there is nystagmus in the abducting eye. In MS, internuclear ophthalmoplegia is often bilateral. Other cranial nerves may rarely be affected by lesions within the brain stem (III, IV, V, VI, VII, pseudobulbar palsy). Charcot’s triad consists of nystagmus, intention tremor and scanning speech, but occurs in only 10% of patients.

3.

Look for Lhermitte’s sign (an electric shock-like sensation in the limbs or trunk following neck flexion). This can also be caused by other disorders of the cervical spine, such as subacute combined degeneration of the cord, cervical spondylosis, cervical cord tumour, foramen magnum tumours, nitrous oxide abuse and mantle irradiation.

4.

Rarely, Devic’s disease, usually seen in children or young adults, is present (bilateral optic neuritis and transverse myelitis occurring within a few weeks of one another) and may be a variant of MS.

Investigations

The differential diagnosis of multiple CNS lesions includes SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, Behçet’s disease, small vessel ischaemia, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis,

meningovascular syphilis, paraneoplastic effects of carcinoma, sarcoidosis, Lyme disease and multiple emboli from any source. It is important to distinguish MS affecting predominantly the spinal cord from other diseases – especially subacute combined degeneration of the cord (more common in the older population) and spinal cord compression presenting with root pain and persistent levels of sensory loss.

MS is essentially a clinical diagnosis, but the following tests may be helpful.

1.

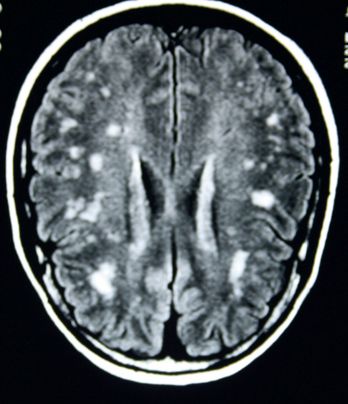

MRI is the imaging modality of choice (

Fig 12.1

).

Table 12.1

lists the typical sites of changes. Typical changes are present in the great majority of patients with MS. Gadolinium contrast studies show leakage into the brain from blood vessels for up to months after the formation of a new lesion. T2-weighted images will show persisting changes probably owing to a combination of oedema, gliosis and inflammation. The extent of these abnormalities does not correlate well with the clinical picture, but T1-weighted images may show hypodense areas whose extent does correspond to the patient’s symptoms. These probably represent irreversible damage and axonal loss. CT scan may reveal low-density, sometimes contrast-enhancing, plaques in white matter (subcortical or periventricular, but only in 10–50% of cases). CT scanning is no longer in routine use for diagnosis of MS.

FIGURE 12.1

MRI of the brain of a patient with multiple sclerosis showing numerous plaques (white patches). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

2.

Visual-evoked responses are delayed in 80% of established cases and indicate previous optic neuritis (important if there is only one other clinically detectable lesion present). Auditory-evoked responses and somatosensory-evoked responses may be abnormal, but are not usually diagnostic.

3.

Cerebrospinal fluid in chronic MS contains oligoclonal IgG bands (70%) and an altered IgG:albumin ratio. Myelin basic protein may be elevated in acute demyelination. There are usually fewer than 50 white cells per millilitre in the cerebrospinal fluid, but acute severe demyelination may result in a cell count exceeding 100/mL.

4.

Antimyelin antibodies are of uncertain value.

A definite diagnosis is not possible without the presence of two or more CNS episodes, usually separated in time and place. The first may be a clinical abnormality and the second detected by MRI or visual-evoked responses (Macdonald criteria). These include objective CNS changes usually involving long tract signs and symptoms: pyramidal, cerebellar, optic nerve, posterior columns and medial longitudinal fasciculus. Gradual progression of symptoms may be used to make the diagnosis if typical cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities are present. The MRI should show four distinct areas of abnormality at least 3 mm in diameter. There should be no other explanation for the symptoms (see above).

Treatment

There are two aspects to treatment of these patients: (1) supportive and symptomatic treatment; and (2) attempts to alter the disease progression. In addition, there are many support groups and organisations for patients with MS. These often give sensible advice to these distressed people and should be recommended to patients. It is most important, however, that the diagnosis is secure before patients are labelled with this condition with its numerous long-term implications.

1.

The course of the disease:

a.

relapsing–remitting MS:

relapses with or without complete recovery, but stable between episodes. Offer disease-modifying therapy

b.

secondary progressive MS:

about half of the patients with relapsing– remitting MS develop secondary progressive MS within 10 years. They experience gradual progression of their symptoms without distinct episodes

c.

primary progressive MS:

these patients (10%) have increasing symptoms without distinct episodes from the start

d.

progressive relapsing MS:

in these patients there is gradual worsening with episodes of deterioration occurring later in the course of the illness.

2.

General support is essential. During exacerbations, bed rest with meticulous nursing is vital. Treatment of bladder dysfunction, severe spasticity (e.g. with baclofen), urgency (e.g. with amitriptyline), tic douloureux and facial spasm (e.g. carbamazepine and physiotherapy) is important. Intention tremor can be treated with propranolol or clonazepam.

3.

Drug treatment: immunomodulators and immunosuppresants.

a.

Interferon beta 1a and interferon beta 1b have been shown to reduce the frequency of exacerbations by about one-third when used at an early stage of disease and to reduce the accumulation of CNS white matter lesions. They are more effective for the relapsing forms of the disease (see below). Remember the risk of hepatotoxicity and leucopenia; monitor blood tests.

b.

Glatiramer acetate (subcutaneous) takes up to a year to provide benefit; the drug can induce non-cardiac chest pain. It is of similar efficacy to interferon. Bradycardia can be a problem.

c.

Natalizumab (monoclonal antibody to alpha 4 integrin) is more effective than these agents, but its use is restricted to patients with very aggressive disease because 1 in 600 patients treated develop progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy due to brain infection with the Jakob-Creuztfeld agent.

d.

Fingolimod is an oral agent that has recently become available. It works via the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor to prevent lymphocyte tracking through lymph nodes. It causes reversible lymphopenia. It has been shown to be more effective than interferon with relapse rates of 25% at 2 years. Side-effects include macular oedema and increased infection risk. It should not be given to people without varicella immunisation or known previous exposure and immunity.

e.

Treatment for aggressive or unresponsive disease: methotrexate given in weekly doses of 7.5 mg reduces the progression of disability and the MRI signs of disease activity for up to 2 years. Azathioprine (2–3 mg/kg/day) is sometimes used for chronic progressive disease and appears to have a modest beneficial effect. Cyclophosphamide may slow progression in patients under the age of 40. Its side-effects make it difficult to use. Mitoxantrone has been used in rapidly progressive disease, but causes cardiac toxicity. Occasionally, autologous stem cell transplant has been used.

f.

Acute relapses are treated with methylprednislone −1 gm/day for 3 doses. Plasmapheresis and intravenous gammaglobulin may help relapses when steroids fail. Treatment of relapses may hasten recovery but does not improve the long-term outlook or reduce the risk of further relapses.

At 15 years after the first episode, 80% of patients have significant symptoms that prevent them from working and require help with normal activities. If the initial episode is limited to a single abnormality and the MRI is normal, only 10% will go on to develop a second episode over the following 10 years. If the MRI is abnormal, up to 80% will experience further episodes.

As with all chronic and debilitating diseases a discussion about the patient’s expectations and prognosis and plans for the future is important.

Myasthenia gravis

This chronic auto-immune disease presents both diagnostic and management problems. Peak incidence in women is in the third decade of life, but in men it is in the seventh decade. Overall it is more common in women (2:1). Exacerbations and remissions (incomplete) are common.

The history

1.

Ask about symptoms at presentation:

a.

ocular – diplopia (90%), drooping eyelids

b.

bulbar – choking (weakness of pharyngeal muscles), dysarthria, difficulty (especially fatigue) when chewing or swallowing

c.

limb girdle – proximal muscle weakness; there is fatigue on exertion and prompt partial recovery on resting.

2.

Ask about a history of difficult anaesthesia (owing to prolonged weakness after muscle relaxation) and past episodes of pneumonia (as a result of bulbar and respiratory weakness).

3.

Determine how the diagnosis was made, including whether electrodiagnostic studies were done and whether the patient had blood tests for acetylcholine receptor antibodies.

4.

Ask about a history of thymectomy.

5.

Enquire about other treatment – including drug dose and when the last dose was taken, plasma exchange or immunosuppressive therapy.

6.

Ask about drug use, which may interfere with neuromuscular transmission (see below).

7.

Ask about other organ-specific autoimmune disease associations (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis).

8.

Enquire about the social history.

The examination

1.

Examine for muscle fatigue, particularly the elevators of the eyelids and the oculomotor muscles (tested by sustained upward gaze), bulbar muscles (tested by counting or reading aloud) and the proximal limb girdles (tested by holding the arms above the head).

2.

Look for the Peek sign (orbicularis oculi weakness – close the eyelids: within 30 seconds in myasthenia they will begin to separate and you will see the lower sclera).

3.

Asking the patient to smile may produce a snarling expression. Speech on prolonged speaking may sound dysarthric or nasal because of weakness of the palate.

4.

Weakness of neck flexion may be prominent.

5.

Look for a thymectomy scar.

6.

Reflexes are preserved, there is no sensory loss and muscle atrophy is usually minimal.

Investigations

Tests for myasthenia gravis (

Fig 12.2

) include the following.