Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (16 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

10.

A patient with familial hypertriglyceridaemia will have been managed in a similar way and may have required treatment for acute pancreatitis.

11.

Patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia are unlikely to live long enough to be present in clinical examinations, but treatment can sometimes involve repeated plasma exchange and even liver transplantation.

12.

When patients have muscle pains on statin treatment, reducing the dose or even giving the drug second daily may be worth trying. However, there are no trials showing that second daily treatment is effective.

Hypertension

Many long cases are likely to provide the examiners with an opportunity to ask about the management of hypertension. Although it is an increasingly complicated subject, it is unlikely to be a patient’s major problem. The examiners will want to hear sensible discussion from the candidate about a number of aspects of hypertension, including the diagnosis, appropriate investigations and approaches to treatment.

The history

1.

Many patients are well informed about and very interested in their blood pressure. Find out when the diagnosis was made and what sorts of blood pressure readings were obtained before and after treatment. It is common for measurements to be made in a number of ways and in different settings. Apart from clinic measurements, the patient may have taken and continue to take his or her own blood pressure at home. There may have been ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) recordings made. It seems

clear that hypertensive risk is more closely related to non-clinic and ABP results than to those obtained in the outpatient clinic. ABP should, however, be lower than clinic readings to be considered normal. Measurements of <135/85 mmHg during the day and <120/75 mmHg at night are considered normal for ABP recordings. See

Table 5.4

for the current classification of clinic blood pressure levels.

Table 5.4

Classification of blood pressure by severity

| CATEGORY | SYSTOLIC (MMHG) | DIASTOLIC (MMHG) |

| Optimal | <120 and | <80 |

| Normal | 120–129 and/or | 80–84 |

| High normal | 130–139 and/or | 85–89 |

| Mild hypertension (grade 1) | 140–159 and/or | 90–99 |

| Moderate hypertension (grade 2) | 160–179 and/or | 100–109 |

| Severe hypertension (grade 3) | ≥180 and/or | 110 |

| Isolated systolic hypertension | >140 and | <90 |

Source:

2003 European Society of Hypertension – European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension.

Journal of Hypertension

2003, 21:1011–1053.

2.

Ask about current and past antihypertensive treatment and about problems or side-effects caused by treatment. Next find out about possible complications of hypertension. These include stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease and renal failure.

3.

Occasionally there may be symptoms that suggest a secondary cause of hypertension: paroxysmal sweating, palpitations and headache (phaeochromocytoma) or daytime sleepiness (sleep apnoea). Rarely, the patient may be aware of a diagnosis of renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta or an adrenal tumour. Primary hyperaldosteronism is now more often recognised.

4.

Ask about other risk factors for vascular disease, especially type 2 diabetes, but also hyperlipidaemia, a family history of premature coronary disease or stroke. The presence of any of these conditions, or of existing heart failure, coronary or cerebrovascular disease, is a strong indication for treatment.

5.

There are often a number of factors that contribute to the problem. These include obesity, excess alcohol consumption, lack of physical exercise and a high salt intake. Other factors, such as cigarette smoking, add to the patient’s overall risk. Ask what the patient knows about these factors and what efforts (if any) have been made to correct them. Some racial groups have a high risk of premature vascular disease and will benefit more from early and aggressive treatment. These include Aboriginal Australians, Torres Strait Islanders and Pacific Islanders.

The examination

See

Ch 16

. Don’t miss Cushing’s syndrome. Feel for radio-femoral delay.

Investigations

1.

Test the urine for protein

. Measure the serum electrolyte and creatinine, blood sugar, cholesterol and haemoglobin levels.

2.

Note the serum potassium

. The presence of hypokalaemia in patients who are not on diuretics should prompt investigations for primary aldosteronism. Measurement of plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma aldosterone (PA) levels may be indicated. A high PA level and a low PRA level leading to a high aldosterone:renin ratio is consistent

with primary hyperaldosteronism. The test is better performed off treatment. Other causes of hypokalaemia and hypertension include renovascular disease (where both aldosterone and renin are elevated), Cushing’s syndrome, chronic liquorice ingestion, Liddle’s syndrome and, in young patients, renin-secreting cancers (rarely).

3.

Ask about snoring

. A history of snoring and obesity should be investigated with sleep studies for sleep apnoea.

4.

Perform a CT angiogram or conventional renal angiogram for patients with intractable hypertension (especially young patients)

. These are the most sensitive tests for renal artery stenosis.

5.

Ask about symptoms consistent with a phaeochromocytoma

. These need investigation with 24-hour urinary catecholamines.

6.

Investigate for Cushing’s syndrome if there is any clinical suspicion

.

7.

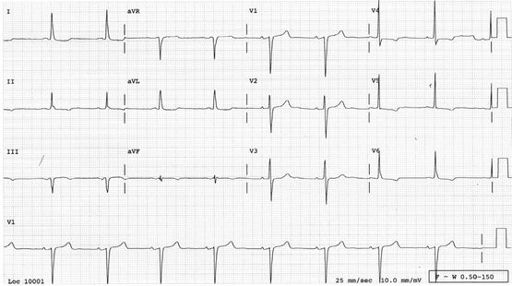

Perform an ECG to look for evidence of ischaemic heart disease and for voltage changes that suggest left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

(

Fig 5.10

). The presence of LVH on the ECG in hypertensives is associated with an adverse prognosis. Occasionally an echocardiogram is indicated if there is doubt about the presence of LVH.

FIGURE 5.10

Sinus rhythm. Left ventricular hypertrophy – the R waves are tall in the lateral leads and the S waves are deep in the septal leads. There are also lateral ST and T wave changes, called a strain pattern.

Treatment

The decision to begin drug treatment is an important one because it is likely to be lifelong. The current recommendations are that a blood pressure of >140 mmHg systolic or >90 mmHg diastolic, or both, warrants a ‘treatment plan’. It is now very clear that the aggressiveness of intervention depends very much on factors other than the blood pressure level. The whole gamut of cardiovascular risk factors must be taken into account.

Tables have been published by many cardiovascular societies that show the calculated risk of vascular events and the calculated reduction in number of events over time with treatment for patients with different risk factors. The decision to use drug treatment

should be based on information of this kind. Typically, calculators of risk take into account age, sex, smoking status, level of blood pressure, cholesterol, race and existing cardiovascular disease.

Except for very severe hypertension, attempts should be made to bring the blood pressure down by modifying the factors that are known to increase it. Many patients, when faced with the threat of lifelong drug treatment, are amenable to suggestions to change the way they live.

Primary hyperaldosteronism can be treated effectively with spironolactone. Renal artery stenosis may be amenable to balloon angioplasty. This usually makes blood pressure control easier, but does not cure the condition. Treatment of sleep apnoea with an appropriate continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) mask can also make blood pressure control easier.

Patients with only a mild risk of cardiovascular problems and blood pressure <150/95 mmHg should probably continue with conservative measures and be reassessed. However, at higher levels of blood pressure than this, drug treatment should be considered. Patients with very high risk (e.g. those with target organ disease or of Aboriginal race) should begin drug treatment if the blood pressure remains above 140/90 mmHg. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly deserves therapy!

BLOOD PRESSURE REDUCTION WITHOUT DRUGS

1.

Weight reduction

. On average, 1 kg of weight loss will reduce systolic blood pressure by 2 mmHg. The goal should be reduction to a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m

2

and a waist circumference of <94 cm for men and <80 cm for women. Even lower BMIs should be recommended for some racial groups, such as Asians and Aboriginal Australians, whose cardiovascular risk increases at lower BMIs than does Europeans.

2.

Exercise

. Thirty minutes of moderately intense exercise (e.g. brisk walking) at least 5 days a week can lower blood pressure by about 3–5 mmHg.

3.

Alcohol

. Reductions of 4–5 mmHg can be achieved by alcohol restriction to two standard drinks per day for men and one per day for women.

4.

Salt

. Reduction in salt consumption to 90 mmol/day can reduce blood pressure by more than 5 mmHg. Warn patients that prepared and snack foods are usually heavily salted.

The cumulative effect of these measures can be considerable, but repeated encouragement is likely to be required for patients to achieve them.

DRUG TREATMENT

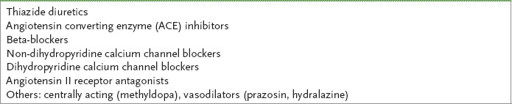

Remember that all classes of drugs (see

Table 5.5

) are fairly similar in their effect on blood pressure. The majority of patients will require more than one drug for effective blood pressure control.

Table 5.5

Classes of antihypertensive drugs

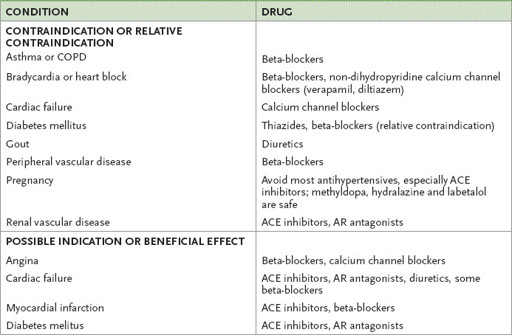

There are many factors to be taken into account when a choice of antihypertensive drug is made (

Table 5.6

):

Table 5.6

Factors affecting choice of antihypertensive drug

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACE = angiostensin-converting enzyme; AR = angiotensin receptor.

•

previous intolerance to a class of drugs