The One and Only Zoe Lama

Read The One and Only Zoe Lama Online

Authors: Tish Cohen

Tish Cohen

For Lucas and Max

Babies Are a Pain in the Eardrum

There’ll Be No Stepping Up in My Absence. None.

Words Made of Churning Bubbles of Intestinal Gases Are Not Words. They’re Sewage.

The Missing Link Is Not So Missing Anymore

There Is No Excuse for Guys Named Thunder Who Stand on Windy Cliffs

Rules Were Made to Be Spoken. Out Loud.

Clear Your Head of Googly-Eyed Puppies

Amateur Orthodontia Is Not Permitted in the Cafeteria

If You Must Cheat Death, Remember to Tell Your Boyfriend About It Later

Rule by Humiliation. You Know, in the Name of World Peace.

Sparkles Are for Good Witches of the North and LameWizard Lovers

Backyards Full of Trees Are Poltergeist Movies Waiting to Happen

Storybook Cottages Belong in Storybooks

Paddling Pools Can Hold a Guinea Pig’s Attention for Only So Long

Guinea Pigs Should NOT Smell Like Rabbits

“I’ll Be the Sandbar Beneath Your Feet” Is Not a Song

Frolicking Puppy Wallpaper Can Protect You from Exactly Nothing

Bad Jokes Come Before Boston Creams

Nothing Mops Up Brain Sweat Like a Good Book

You Gotta Know When to Fold ’Em

Sometimes a Cigar Is Just a Cigar

I hate going to the doctor.

It’s total chaos. The entire waiting room is coated with a thin, gluey glaze of mucus. The walls, the receptionist’s desk, even the Kleenex box—all sticky. And don’t even get me started on the fish tank. The floor is crawling with feverish brats thumping one another with plastic tricycles, and you’re never going to find a place to sit, because all the spare seats have spit-up on them.

Nothing against Dr. Jensen, other than the way he sings Beatles songs while he looks into your ear, he’s an okay guy for a pediatrician. And if you survive your checkup without wailing, vomiting, or stealing his latex gloves—so you can fill them with water and launch them out your bedroom window later—he gives you an animal cookie on your way out. I don’t mind that they aren’t chocolate chip cookies. I’m twelve years old, plenty old enough to know it’s easier to bribe a blubbering kid with food if it’s shaped like an alligator.

I do blame Mrs. Chomsky, his angry receptionist. She just sits in her spinny chair, answering the phone and slapping files on the counter for Dr. Jensen.

Well, it’s her lucky day.

I’ve been home with chicken pox for eight days, twenty-two hours, and thirteen minutes. Not that I’m counting.

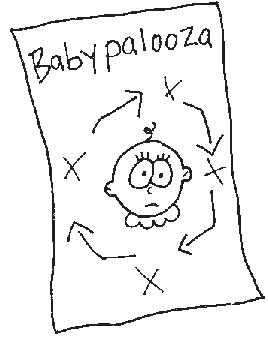

Dr. Jenkins said, “No school, no friends, no fun.” He didn’t actually say the no-fun part, but he should have, because I was bored. And major itchy. I knew I had to come for another checkup before I was allowed back in school, so when I wasn’t scratching or dreaming about scratching, I was drawing up a diagram for old Mrs. Chomsky. I colored my diagram, labeled it with instructions, and snuck out of the house to get it laminated. (If you ask me, everything in this entire place should be laminated. To make it snot-proof.)

My diagram is based on my one and only rule about babies. I may not have any babies in my family—or any brothers or sisters or fathers, for that matter—but here it is anyway,

Unwritten Rule #15—Babies are a pain in the eardrum, so you better keep them busy while they’re waiting to see the doctor.

My system is based on stations. Keep babies and toddlers moving, don’t give them a second to think! Thinking only gets them into trouble, because their heads are still so small. They really only have room for two thoughts:

How loud should I scream?

and

Who can I whack next?

Both of these behaviors are hugely annoying and, as I’ve mapped out, can be avoided by moving babies from one station to another in three-minute intervals.

You start them off in the Bottle and Juice Station for energy. Then, when the bell rings, they move to the Recreation Station (tricycles) for exercise. Then the bell rings and they move to the Nature Station (fish). After three minutes with their faces glued to the dirty glass, it’s over to the Hygiene Station to be scrubbed down with antibacterial wipes. Then three minutes to chew on a book and start all over again.

Simple, really. The mothers do all the work. All Mrs. Chomsky has to do is ring a tiny bell every three minutes and the place should run like spit.

T

he moment Dr. Jensen calls my name, I pull out my bell and my diagram—titled “Babypalooza”—and set it

on Chomsky’s desk. There. I’ve done all I can. Like my grandma used to say to me when I was younger, “You can lead a horse to the bathtub, but you can’t make her wash behind her ears.” Which never even made sense, because after she said it, my mom made me wash behind my ears.

My mother and I follow Dr. Jensen into the examining room. No matter what I’m in for, the drill’s always the same. He dances me into the examining room, tells me to take off my shoes, and makes me hold still to get measured. He never bothers to tell me how tall I am—or am

not

—he just scratches something in my file and says, “Not to worry.

What you lack in the size department, you make up for with your gigantic personality!”

Afterward, he scoops me up onto the examining table and the crinkly paper pokes me hard in the back of my knee.

“And how are our spots today, Miss Zoë Monday Costello?”

Next time I come, I swear, I’m bringing some Wite-Out for that middle name. “Pretty okay.” I roll up my sleeves and show him my arms. “Not nearly so spotty.”

“I followed all your advice, Dr. Jensen,” says my mother

with a tight little smile. “Oatmeal baths, sea-salt baths. Even the tea-tree oil. Just like you said. Dr. Jensen’s advice made an enormous difference, didn’t it, Zoë?”

“Kind of.”

My mother is blushing. She doesn’t know I know what I know, but I know it. My mother has a teensy crush on Dr. Jensen. He just thinks she’s friendly, but she’s not fooling me. She’s never

this

friendly.

“Good,” he says, pulling out his little flashlight. He looks in my eyes, in my ears, then shoves a Popsicle stick in my mouth. His hair is like an unraveling SOS pad, springing up from his head in every direction. “Say ahhh.”

“Ahhh.”

“Good.” Then he shines his light up my nose and makes a happy grunt. “I see the pustules in your right nostril have dried up nicely.”

I don’t answer on the grounds that having anything as vile and horrid as “pustules” up my nostril is so embarrassing it takes my words away. I mean, I’m a good person. Sort of. I take care of my mother, my classmates, my teachers, even my grandma, and she doesn’t even live with us anymore. I take care of her every Sunday at the Shady Gardens

Home for Seniors by making sure the staff doesn’t give her lumpy cocoa. I even take care of the old collie that sleeps under the Shady Gardens nurses’ station by filing his toenails and painting them with Mom’s favorite nail polish—Midnight Mango.

With all these good works,

I consider gruesome boils inside my innocent nose to be an Act of Hostility on the Part of the Universe.

“Does your nose feel better?” Dr. Jensen asks me. Loudly.

Trying to ignore him, I sniff and lean down to fakescratch my ankle, wishing a tornado, a bobcat, or a rashy toddler would burst through the door. Anything to change this sickening subject.

“Zoë?” he says.

“What?”

“Your right nostril. How is it?”

“Umm…”

“Zoë, darling, answer Dr. Jensen,” says my mom. I can tell by her voice that I’m going to hear about this in the car.

Dr. Jensen looks up my nose again. “Are your pustules causing less discomfort now?”

My

pustules? Ugh. I look away, toward a square tin decorated

with blue swirls. On the lid, it says

BOVINE BALM

. “What’s that?” I ask.

It works. He looks toward the tin and laughs. “That, Miss Zoë, is a trade secret. My hands get dry and cracked from washing them between patients. I’d heard that this stuff was a miracle moisturizer, so I hunted around for it and what do you think happened?”

I shrug. I really don’t know.

“I found it at the drugstore in the lobby downstairs. Only $4.99.”

“Four ninety-nine?” squeaks my mother.

“Well, it sounds like you’re a man with good economic sense.”

Dr. Jensen opens the lid and shows the clear goo to my mother, who pretends she’s impressed. I’m thinking it smells like Vaseline, when my mom asks, “Doesn’t

bovine

mean for cows?”

Dr. Jensen laughs. “That’s why I was surprised to find it at the drugstore. It’s made to moisturize the tired, cracked teats of milking cows.”

He bends over to write my back-to-school note while my mother rubs the Bovine Balm into her hands. “It does feel marvelous,” she says.

He scoops some out. “I bet this stuff is even strong enough to keep my hair in place. Now

that

would be a miracle.” Which gives me an idea.

I have a lot of clients at school. Which is why I have the nickname Zoë Lama.

Kids, teachers—even principals—come to me to solve their every problem. And I care about them all, I truly do. But some are just…special. Like Sylvia Smye. She’s been with me ever since the day in first grade that kids still refer to as “The Great Barrette Disaster.” Sylvia’s mother tried to tame some of her daughter’s cowlicks using yellow ducky barrettes, but by the end of the day, her hair stuck straight up like a horn in the front and Smartin Granitstein started calling her “Unicorn.” No matter what I did, I couldn’t flatten her hair, so I dug around at the back of my desk for some dusty rubber bands and built myself a horn of my own and then convinced the other girls to do the same.

Icktopia

Icktopia