Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 (65 page)

Read Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 Online

Authors: Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Germany, #Great Britain, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #World War II, #History, #Reference, #Words; Language & Grammar, #Rhetoric, #England

The theme is established in the opening sequence: it is dark, and Islanders are seen lowering a small boat down a wall at the water's edge. Some men are keeping watch while others load cases into the boat and help to launch it out to sea. As the boat is rowed away from the Island, a group of men stand on the wall and wave as the narrator intones, “Good luck! When you get to England, tell them how we're getting on over here. Tell them we're having a tough time but the Germans can't get us down. And tell them more of us will be following you. And tell them in spite of everything we're managing to hear the BBC.” It is this concept of carrying on under tough conditions and not allowing the enemy to prevail that carries through this little film.

It really is a fascinating view into the Occupation, as the Islanders had a final chance to wear their tattered everyday clothes as costumes for the film before they were discarded, burned, or folded away in attics as part of private memories. The film moves through scenes of want and make-do (“As for clothes, it was a case of mending and mending”), the disturbing sight of slave laborers (“We were sorry for those slave workers; we'd seen the way they were treated”), and the empty Market of the final year (“There was the black market if you could afford it, but for ordinary decent people it was always the same, ‘No, I'm sorry. Nothing.’”). And there were the triumphs of the

Vega

's arrival and the joy of Liberation (“We forgot we were hungry. We forgot everything except that we were free.”). One response to Liberation that was discussed in this chapter is verified by a segment of the film. The film takes the standpoint that, as food poured in and the shops were newly filled with goods that had not been seen for years, it all seemed to be a dream to the Islanders: “We went about in a sort of daze. Hardly daring to touch anything for fear that we would wake up and find that it wasn't real.”

Most interesting from the standpoint of this current study is the move made by the film to juxtapose the experience of the Islanders with that of their British mainland counterparts. It is an initial attempt to show mainlanders that although the Islanders had not slept in fallout shelters or suffered under bombardment as did British mainland civilians, they did experience the prolonged suffering of hunger and deprivation. A key moment to stake the ground of this position came during scenes of Liberation, when ragged and largely barefoot children were shown eating oranges while sitting on a seawall. The narrator explains, “Most of your children know what an orange looks like, but our younger ones had never seen one. They had to be shown how to peel one.” This stance was strengthened when the film returned at Liberation to a couple, introduced earlier, who had struggled to feed their children during the Occupation: “Jack and Florey Steele, and that means all of us, had their first normal British meal: a cut

off the joint and two veg. The sort of meal you've been having once a week ever since 1939.” Perhaps the Islanders had not experienced the continuous threat of air raids, but, the narrator implies, although mainland Britons had been living under rationing, they had little idea of real hunger. It was an initial salvo in the brief post-Liberation war of comparative experience.

Despite the human interest of these more domestic scenes, the film justifies the Islanders' experience the most during the adventure sequences. First established is the response of Islanders during the arrival of the Germans, and the panoptical nature of Occupation as a whole. Early in the film, the narrator describes how “When the Germans arrived in 1940, our first reactions to them were probably the same as yours would have been.” The script thus connects the patriotism and resistant nature of the Islanders to their British mainland counterparts. But here the visuals are particularly instructive. German tanks are shown rolling along the road by the water, and there is a cross-fade to an old man, the typical Islander attired in a working-class cap, looking down from a high window and spitting (the “first reaction” to the Germans demonstrated in a clear sign of contempt).

As a tank goes past a petrol station, an old woman with round glasses looks out her open window past her lace curtains and then withdraws, allowing the curtain to fall, obscuring her presence. Thus is shown not only the Islanders' antagonism to the occupying forces and their determination to stand apart from them in opposition but also the

sousveillance

that civilians would adopt as a primary tactic of resistance. The woman, who continues to monitor the troops while shielding herself from observation behind her lace curtains, provides a strong visual metaphor for this technique. The Islanders would constantly watch and “read” the Germans in their midst while drawing an impenetrable veil over their own activities.

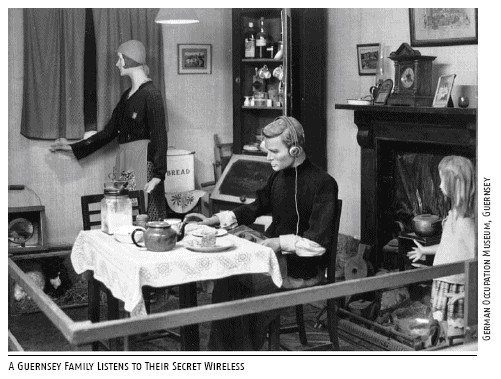

But it would not be an adventure story without displays of overt resistance. The film shows two men in the dark of a small and secret room, listening to a hidden radio and writing by the light of a flickering candle. The narrator, having described German confiscation of goods, explains the scene: “But, worst of all, they stole the truth, and filled our newspapers with Goebbels and Haw Haw. The remedy was simple but dangerous. We ran our own with the help of the BBC.” Then begins a section where the narrator describes GUNS and introduces Nick Robbins, a junior reporter, and his role in the underground news distribution. As the next series of visuals unfold, the narrator explains their importance in flat, unemotional tones: “The originator, Marchon of the

Guernsey Star

, was eventually caught and sent to Germany where he died, poor chap. Falla and Duquemin also went to prison.”

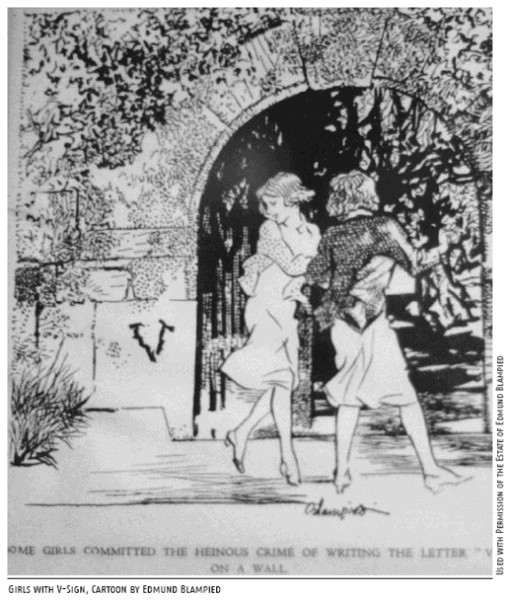

A young man is shown typing a page headed Feb. 1943 and making the large V made out of small “v's” that was the hallmark of GUNS. Leaving his hidden room and heading down a dark staircase, he emerges into the daylight of the street past a sign in the window, “Advertise in The Star.” Two German officers are shown at the top of a steep flight of Guernsey steps that the young man, attired in a trench coat straight out of any spy film, starts to run up. He stops and looks up as the Germans give each other the Nazi salute and go their separate ways. The young man turns, takes the typewritten sheets from their hiding place in his sock, and slides the papers through an opening under the door. Then comes a series of scenes to represent the flow of news. The young man knocking at a door and talking to an old woman, another young man selling papers and whispering to another man who stops to buy a paper, a woman milking a cow when a man comes up and whispers something to her. The narrator explains, “That's one of the ways news got around.”

The final notable aspect of the film is the way that it handles collaborators and other traitors to the British cause. It does not take up the more delicate issue of so-called “horizontal

collaboration”

159

and leaves the sexual dalliances of women with the German soldiers unmentioned. But the film is blunt about profiteers and informers:

It was really a shame about our traitors, people who would spit on you for a handful of dirty marks. There wasn't many of them, but we shan't forget them. They used to write anonymous letters to the Gestapo telling them where they could find hidden radios. But the post office workers had a way of dealing with these letters. A great many of them never reached the Gestapo.

Postal workers are shown sorting mail. One middle-aged worker in the foreground, apparently Rev. Ord's friend, Henry Martin Lihou, playing himself,

160

pauses in his sorting to examine a letter. A close-up reveals that the letter has been very generally addressed to reach the commandant at the Grange Lodge, thus marking it as coming from an informant. The postal worker looks up to check if he is being monitored; then he quietly slips the letter in his pocket. The message of the sequence is clear: the Islanders did not accept the traitors in their midst and had their own means of dealing with them. It would not be dramatic, and perhaps not as satisfying to some, but under the right circumstances, it could be effective.

This is the message, too, in the little piece of retaliation hinted at in the close of the film. The Germans are shown as being set to the “thoroughly unpleasant job of removing the 200,000 mines they laid in four Islands. And that goes for the barbed wire, too. No one has suggested giving them gloves.” The written description of this film in the Imperial War Museum where it is housed calls this specific reference “vindictive commentary,” but it is much the favored style of humor of the time. It shows quite plainly where Islander sentiments reside, and makes the point that they had their own ways of balancing the books.

Before leaving the topic of public memory, a word should be given to the German Occupation Museum, founded and directed by Richard Heaume. Born during the final years of the war, Richard collected artifacts of the Occupation as a child and a young man, and it was to house his growing collection that he opened a museum in 1966. For many years he ran the museum rather like a hobby. However, his avocation became his vocation, and for many years he has directed the museum full time. I mention this evolution because the German Occupation Museum is an example of vernacular memorializing that over the years has gained official status. It is the Occupation as viewed by the average Guernseyman and woman who experienced it. Richard brings to the museum both the professional and careful quality of the historian and the warmth of familiarity with a given time and place. There is a charm to the mannequins used throughout to represent the Islanders, for they have that slightly stunned appearance of all figures frozen in place. Yet, dressed in the clothes of the day, especially in the Occupation Street addition to the main museum that shows a tableau of Guernsey life under Occupation, they are effective in “peopling” the displays and providing a glimpse into the war years of the Island.