Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 (64 page)

Read Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 Online

Authors: Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Germany, #Great Britain, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #World War II, #History, #Reference, #Words; Language & Grammar, #Rhetoric, #England

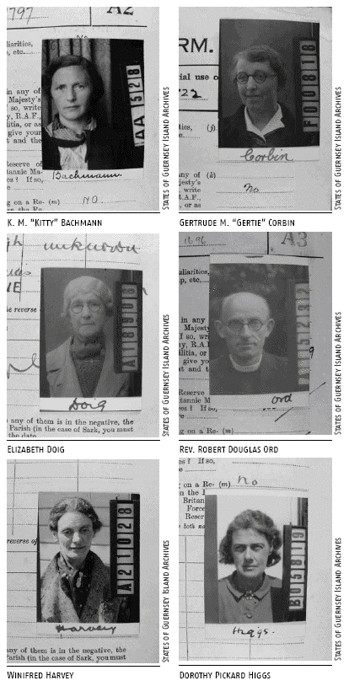

The formidable Winifred Harvey “won” the Battle of Newlands, as her published diary was called, and returned to her home to live there until 1975, when age and infirmity forced her to leave.

147

She died the following year after a rich life of eighty-eight years. Kitty Bachmann's diary was published, with her evacuated daughter Diana de La Rue providing the charming illustrations of an Occupation that she only experienced through her family's stories. W. A.

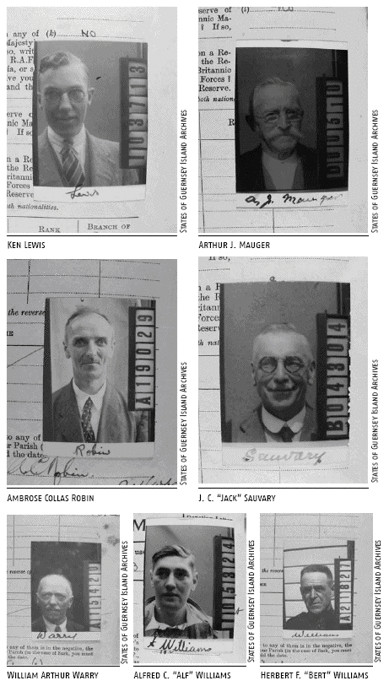

Warry and his wife both survived the Occupation despite their separate health problems. There seemed to be little to write about after the war, and his diary lagged, with only occasional entries until 1952. He recorded that his wife Angeline had died suddenly on April 6, 1950, her seventy-fifth birthday, and was buried April 11 at the Candie Cemetery, followed a month later by her sister.

148

Bill carried on for another eleven years without his wife, dying in 1961 at the age of eighty-two.

Rev. Ord, that adept guide through the Occupation, stayed at Brock Road Church until 1948. His congregation wished for him to stay on longer, although he had far exceeded the number of years that the Methodist Church tended to leave a minister in one location. He left Guernsey to make way for a minister who had been through an illness and for whom the Island location was helpful to his convalescence.

149

His final ministry was in Farnham, Surrey, where he remained following his retirement until his death in 1978.

150

Our other prolific guide, Ken Lewis, ended the Occupation in the same romantic quandary that he had experienced throughout these years. On the same day in late April that he took Vera some lilies of the valley, he mentions that he dreamed the previous night that Brenda Parker had died and Mrs. Parker had been the one to break the news to him. Yet, three days later, he recorded that it was Brenda's twenty-first birthday, so she certainly was not dead to him.

151

I simply had to learn the outcome of this little love story and how life turned out for Ken, so I contacted his son, Nigel Lewis. Brenda actually married someone else and, as of 2004 when I heard from Nigel, was still living in Guernsey. Vera joined the

WRENS

after the war, an interesting proof that any casual contact she had with the young German soldiers was just youthful high spirits and not a negative reflection on her patriotism. The last that Nigel heard of her, she was living overseas.

But Ken did find love, and with someone who reflected his deeply held beliefs. His future wife, Jean, had evacuated to Rugby at the beginning of the Occupation, but when she returned, she attended the Methodist Church in St. Martin where Ken was a youth club leader. They had several children, and on Sundays after lunch, Ken used to read to the family from the diary, although Nigel said he “managed to gloss over the romantic bits.” Ken died of a brain tumor in 1996, and it was then that his son decided that the diary should be in the Island Archives.

152

It is an incredible resource about life under Occupation.

But one of our diarists would not survive for the long-awaited reunion with evacuated family. The reader of Jack Sauvary's diary slowly watches Jack's health change over the years. He first mentions a problem in January 1943 as a weakness in his voice, despite his feeling well, no cough or cold or pain, but just “an awful effort” to speak. Jack was a little anxious about this and took some French medical concoction to get him through Mary's wedding. After all, he was giving her away and needed to come out strongly with the “I do.” He does believe at this early point that he may need to give up smoking and see the doctor.

153

Thus begins the long road familiar to anyone dealing with serious illness, although in this case aggravated by the lack of means to properly diagnose or treat whatever he was experiencing.

It is interesting to gauge Jack's response to this initially mysterious affliction. On the one hand, when undergoing a serious of tests, he immediately equates it with his wife's fatal illness: “It seems to be the same game as with Mother, looking for something that shows no symptoms. I don't understand doctors.”

154

On the other hand, Jack approached illness with his usual humor and hope. He tries various self-remedies, gargling with old port and glycerin, or sitting outside with his shirt open to sunburn his chest, figuring it to be as good as the radium treatments not available to him under Occupation conditions. When pulled into the Emergency

Hospital for tests and asked all the usual questions for admission, such as “where born?” Jack cheerfully added, “Where died? Emergency hospital.” By Easter 1943, he was saddened that he could no longer sing with the choir on the great festival day, but hoped he would someday again: “We always live in hope, they say, if you die in the stairs, never despair.”

155

And so it went for the next two years, with tests alternating with the few attempted treatments that could be mustered in the Island. Jack's voice finally failed entirely, and his breathing made it difficult to climb hills. In January 1945, he was admitted to the Emergency Hospital so that he could be treated quickly if his breathing stopped. With the rest and care, not to mention the better food allowed at the hospital, Jack recovered some of his strength and breathing ability. But by 1945, it was clear to all that his only hope was that the Red Cross would arrange the evacuation of invalids so that he could get the deep x-ray/radium treatments that he needed. It is an interesting window into another time to find that Jack was being told that his problem was “purely functional,” but at the hospital he found out, by the way his plates and dining utensils were marked, that he was being treated for a malignant growth.

By the end of February, despite the war going well, it seemed that the hospital ship would not come, and Jack's entries to his children take on a tone of farewell. He had asked Mrs. Rowe to look out after their “little things” and to keep them safe for his children's return. In March, Dr. Fox personally took Jack back to St. Sampson, a poignant trip that was quite obviously meant as a chance to say goodbye and settle his affairs. Jack was sad that all signs pointed to his not surviving to see his children again, but he treated it as “just misfortune to be stuck here like this” and unable to get lifesaving treatment. Jack tried later in March to stay at his home, but after three days it was obvious that he needed to be in the hospital. So, he said goodbye to old friends and the Front that looked out to sea, now so beautiful in the spring sunshine, and left his home for the last time.

156

Holy Saturday was a difficult day for Jack physically, and for the first time, he wrote of himself in the past tense: “If only this war had finished in time, it might have made all the difference for me.” And by the next day, Easter Sunday, he was poorly enough that he hoped it would be the last he would spend if he was going to feel this way. On Easter Monday, April 2, he managed to go with a blanket wrapped around himself to the women's ward for Communion, the last he expected to ever have on a festival week. But Jack never lost his interest in life or the affairs of the Island. Mr. De Garis, the man whose throat was slit in the milking incident, was in the bed next to him On Monday, three Germans were there typing out information on the attack, and Jack wrote, “Quite a lot of clicking for half an hour.” And there the diary ended.

A letter appended in the published diary from a nurse at the hospital described how Jack's breathing grew worse and he was scheduled for a tracheotomy on April 5. He was doing well the night before and seemed happy, but grew worse the next morning and lapsed into unconsciousness.

157

So slightly over a month before the Occupation ended, kind and cheerful Jack, who wanted little more than a reunion with his children and grandchildren, died on April 5, 1945. He is buried in the St. Sampson's churchyard next to the wife he mourned so deeply. On the stone wall beside the grave are the memorial plaques to their children, Jack, Flo, and Kitty, a symbolic uniting of the family in death that could not occur in life.

Although this study of discourse, sense-making, and rhetorical resistance effectively ends with the close of Occupation, I want to mention two examples of public memory where there has been an effort made to convey the lived experience of those years. The first is a film

made about the Channel Islands soon after Liberation, “starring” the Channel Islanders and some of the Germans, drafted as extras, who were still in the Islands doing cleanup. Directed by Gerald Bryant and produced by the British Ministry of Information,

Channel Islands 1940–1945

is, in effect, a public-relations film to let Britain know that the Channel Islands were working hard to be ready for business once again.

158

It was also a means to share some of the tales of being occupied by the Germans with the many people outside of the Islands interested in the experience. This 16-minute film takes its stylistic cues from the other British mobilization films and attempts to tap the same expectations for exciting viewing formed by the major cinema of the day. Therefore, the film of everyday life is punctuated by adventure sequences, and the narrator, while speaking from an Islander's standpoint, has that cynical, world-weary-yet-determined tone that became familiar in British Ministry of Information films of the war years.