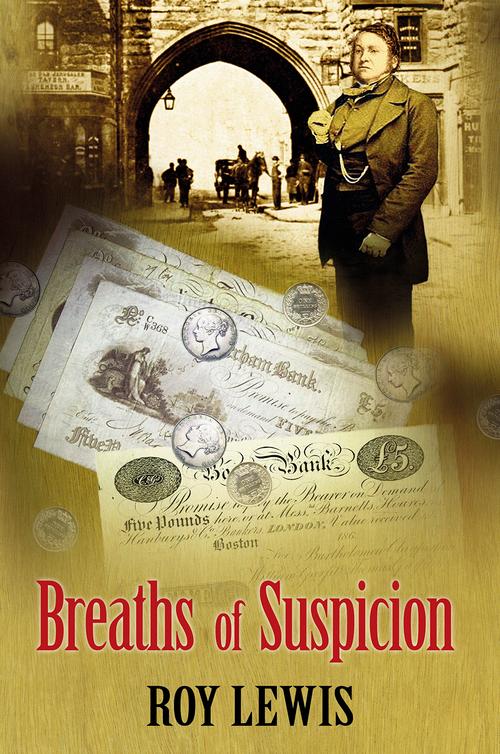

Breaths of Suspicion

Read Breaths of Suspicion Online

Authors: Roy Lewis

ROY LEWIS

L

ooking back, Joe, my boy, I realize I should never have attended that fateful meeting at the Abbey Inn that Sunday.

Not that I really had a great deal of choice. My attendance had been requested by that arch-villain, Lewis Goodman. Since he held a great deal of my paper I knew it would be unwise to refuse to appear. The invitation was more of a demand than a friendly invitation.

Ever since the debacle over the

Running Rein

affair I had been unable to escape Goodman’s clutches. He made no great financial demands upon me—because he knew they would hardly be

satisfied

—and indeed, he refrained from calling in the individual bills when they fell due. In return, of course, he felt able to ask various ‘favours’ of me … and even of these, there had been few.

So, when he called upon me to attend the meeting, I went with trepidation in my heart. I was attending the Assizes at Nottingham at the time so was able to make my reluctant way to the Abbey Inn without difficulty that Sunday. The inn lay at a small distance from the path, among the trees near the main road towards Thoresby. As I approached it I could see it was not a particularly hospitable hostelry: the Abbey Inn had seen better days, when the Plymouth stages had passed by its doors. Now it presented a generally bedraggled appearance, its thatch straggly in places, its windows

darkened with smoke and its yard wandered by unhealthy-looking fowl. The doorway was low, and I had to stoop when I entered.

The dark-ceilinged room I walked into was empty apart from the small group of men huddled around a table in the far corner. There was no fire in the grate, but a swirl of greasy smoke hung like a pall below the grimy, blackened beams. I should have left at that moment as the sharp stench of stale beer and ancient gravy caught at my throat, but Lewis Goodman was already rising to his feet to greet me.

He was smiling, but he did not appear well. Some of his confident air seemed to have deserted him since our last meeting and there were sagging strips of flesh below his suspicious eyes.

‘James! I’m glad you have made an appearance. Come, join us in our discussion.’

I looked past him to the others present. Jem Saward I already recognized as a fellow member of the Inner Temple: I had seen him hanging around the fringes of the courts, notably at the Old Bailey, though he was not reputed to have established a practice of any consequence. Yet he dressed well enough, and his collars and cuffs were always clean; indeed, he presented a certain dandified appearance. I glanced at him, turned to the second man. It was someone once more I recognized: a disreputable individual called Agar whom I had once—at Goodman’s behest—defended. I was not pleased to find myself once more in his company.

The third individual caused me a start of surprise. He was a renowned banker, by the name of Sadleir. We had not been

introduced

but I knew him by sight as a fellow member of the Reform Club. He sat there stiffly in a black frock coat and light tweed trousers, a gold chain stretched across his vest. He seemed ill at ease in this company; out of place. I had a presentiment of danger. I turned to Goodman. ‘You’ll forgive me, but I am a busy man and while your invitation to meet you here was pressing, I fear I must ask that you tell me what this is all about.’

Goodman smiled again: his smile always gave me a slight shiver down my back. He glanced at his companions, and winked broadly. ‘This is a meeting of a group of investors. I asked you here in order that you should be given the opportunity to make your own investment to match ours.’

I felt like laughing in his face. He knew the state of my finances. My debts were escalating at an alarming rate, in spite of the

considerable

income I was receiving as a successful Old Bailey barrister but I was in no position to invest in any project—and would have been disinclined in any case, if he was involved. I was about to say something to this effect when a cold draught touched the back of my neck. I turned, looked back.

Standing in the doorway was my arch-enemy, Lord George Bentinck.

He stood there as though rooted. There was malice in every line of his proud, arrogant body. He stared at me coldly. ‘I thought I recognized you, James, entering this disreputable hovel. I was intrigued. I wondered—’ He paused as his gaze slipped past me to the rest of the company. Slowly, he raised one aristocratic eyebrow. He clearly recognized Goodman, and his handsome lip curled. He looked at the others, silently, took note of the banker, a fellow MP. Then, after several tense moments, he half-turned to leave the room.

Over his shoulder, he said, ‘Well, here we have as fine a parcel of scoundrels as ever one could expect to see!’

The door slammed behind him. For a brief time I remained rigid, unable to move. No one spoke but I felt a raging fury stir in my chest. I had no desire to be in this company; Bentinck hated me and would no doubt at some time in the future find good reason to slander me further, and do all he could to blacken my reputation, seeing me in this company. My anger was directed to Goodman for bringing me here, but also towards Bentinck himself, the arrogant, aristocratic humbug, cheat, fraud and hypocrite.

Goodman a laid a hand on my arm, but I flung it off. I almost ran recklessly and there was a scraping of chairs as the others rose to their feet. I rushed to the door, foolishly, thinking there would be some way of challenging Bentinck, persuading him … but of what?

My action was mindless, careless, but how was I to know that my reaction on that day formed part of events that meant my old enemy had seen his last dawn? For within a matter of twenty minutes my sworn enemy Lord George Bentinck would be stretched lifeless on the edge of the woods—and I would be hurrying back to Nottingham.…

But I am getting ahead of myself again. Parliament. You asked me how I had succeeded in my quest for a seat in Parliament, and I promised to tell you. It’s a complicated story, full of twists and turns, violence and, yes, death.

And while the Abbey Inn played its part, I need to start before that fateful, and fatal day at the disreputable hostelry near Thoresby. Parliament, ah yes.… It would offer me a glittering future, and could be a haven for me, avoiding my creditors and my enemies.…

B

ig Ed.

It could have been that, you know, rather than Big Ben. When I was returned on the second occasion, as the Member for Marylebone in the Liberal interest, it was in the company of Sir Benjamin Hall: in fact, the second time I was elected I topped the poll with 5,194 votes as against Ben’s total of 4,015. Anyway, Sir Benjamin and I were the two sitting members at Marylebone at the time the great clock was mooted, and if things hadn’t gone, shall we say, rather badly for me, with my enemies closing ranks in a concerted attack upon me about that period, Big Ed it could have been, rather than Big Ben.

And Big Ed has a certain

ring

about it, don’t you agree? A certain

tone

. Hah! You laughed!

Of course, in those days before I had even met your mother, I wasn’t known as Ed, not in England, even within the family: my parents, brothers and sisters, they all referred to me as Edwin. And at the Bar, professional etiquette always demanded the use of my surname, James. Of course, things were different in the more relaxed social atmosphere in the United States later on, where I spent ten years in the legal and newspaper business. I recall that Walt Whitman called me Ed right from the commencement of our acquaintance. As did Mark Twain and Bret Harte, and John C.

Heenan, bareknuckle champion of the world, when I was arranging his fights in the States and Europe.

But in matters of that kind, things were always less socially stiff across the Atlantic.

However, in London it was James at the Bar; or Edwin in the family; or the Honourable Member for Marylebone when I rose to my feet in the House of Commons.

And for a little while, Big-headed Jimmy, or Necessity James (a quip from that snivelling jackanapes, Henry Hawkins, later to become Mr Justice Hawkins: his constant snide comment being

Necessity knows no Law

). But I’ll get to that. You’ve asked me how it was that I came to be elected the Honourable Member for Marylebone.

Edwin James, QC, MP.…

I don’t recall precisely at what point I set my eyes on election to the House of Commons. I suppose, in a sense, it was a natural ambition. After all, once my father forced me to set aside my leaning towards the footlights (I played in a number of penny gaffs, and even the Theatre Royal in Bath, as a stage-struck young man) and ensured I took up practice at the Bar I felt the need to do well. Thereafter, when I realized I had a talent for the courtroom (which was not unlike a theatre, anyway) ambition drove me to seek high office, if only to prove wrong my father’s sneers at my likely professional failure. And to succeed at the Bar and reach the dizzy heights of Lord Chancellor of England it was, of course,

necessary

to enter into politics. To become Solicitor General or Attorney General demanded a seat in the House, and it did no harm either if one aspired to a judgeship.

Political influence was always a useful shaft in one’s quiver. Indeed, a necessary one.

So once I was launched at the Bar, and found myself gathering laurels for my performances in the courtroom, particularly after the

Running Rein

affair, I also set my sights on Parliament. I have to

admit, I had no great leanings towards a particular political group. Obviously, the Tory party would be a good bet, for it was in power at the time. It was for that reason that I had first sought

membership

of the Carlton Club, in the days of the Tory administration of Sir Robert Peel. You’ll recall I had been frustrated in that attempt by the blackballing machinations of my enemy, Lord George Bentinck, who had never forgiven me for the manner in which I had attacked him in the hearing arising from the Derby of 1844. Since the Carlton was closed to me, I decided that Reform would become my political mission in life and I cultivated the necessary connections among those who sat on the Whig benches in the Commons. And when I was finally proposed for membership of the Reform Club, no black balls were forthcoming, which had not been the case at the Carlton. The first step had been made: I was mingling with the leading Liberals of the day.

As for Bentinck and the Derby business, of course, as I’ve already explained to you, I was never able to make public my discoveries concerning the disappearance of

Running Rein

, the winner of the 1844 race. For some time after the affair a fierce fire burned within me, a desire to make further attacks on Lord George Bentinck, to reveal all I knew to the magistrates and recount the whole explosive affair to the newspapers, but I have to admit that the emotion was not of long duration: the fire was damped down by the fact that actual proofs would be almost impossible to obtain; if everything came out my own reputation could be scarred, and in any event I had become very busy, as briefs flooded into my chambers and I began to be seen as a rising star at the Bar.

So I kept my counsel. While Bentinck simmered on the

sidelines

, nursing his hatred of me.

Talking of my practice, over the course of the next few years after

Running Rein

I gradually abandoned my work in the Bankruptcy Courts, or, at least, I appeared in such causes far less often as other, more remunerative and more attractive opportunities were

presented to me. Newspaper reports of my performance in the

Running Rein

case had brought me to the attention of the litigious public as well as the attorneys, and hacks crowded into the

courtroom

when I appeared, to write up my witty asides in the weekend journals and devote columns to the cross-examinations in which I brought out the more salacious details of life among actresses, aristocrats and members of the flash mob. So, although I was asked from time to time in the clubs to comment on the 1844 Derby affair, I was never able to reveal the entire truth that lay behind the

Running Rein

disappearance, largely because of my indebtedness to that villain, Lewis Goodman. In any event, my practice picked up enormously.

And I have to admit that Goodman himself was behind at least some of my growing success. It was clear to me that many of the clients who came to my chambers arrived there as the result of his recommendations. I would be the last to aver that they were

desirable

clients socially: they counted among their number magsmen and card sharps, insurance fraudsters and night house supporters, pugilists, actresses and clipsmen. But it was all business, and my clerk, Villiers, was kept well occupied. But I also draw attention to the fact that my practice grew not only on the backs of river low-life and acquaintances of Lewis Goodman. The reality was that in those days all levels of society found themselves repairing to the law courts: it was a litigious age. And once it became known among the attorneys that I was a man who could hold his corner, fight a case with vigour and wit and destroy a witness in merciless cross-examination, many of those in high positions in Society beat a path to my door.

And fortunately, the newspapers took note of these sensation cases:

The Times

featured me prominently in its law reports, the

Morning Chronicle

slavered over some of the more intimate details revealed during my cross-examinations in breach of promise cases and I found my growing fame in the courtroom reflected in the

number of social invitations I began to receive from members of the Upper Ten Thousand. In short I was beginning to ascend the social ladders, to the wide-eyed surprise of my father, who had never become reconciled to me since my early stated desire to seek my fortune on the stage. His grudging yearly allowance had finally forced me to the more acceptable pursuit of a career at the Bar, but now that I was succeeding, he seemed oddly out of sorts, having predicted from his lofty position as a Secondary of the City of London that he doubted I would ever settle down to hard work.

And it certainly was hard work. I was never a black letter lawyer: I make no secret of the fact that I made much use of

penurious

devils to raise the salient legal points for me in the more difficult cases, (as that envious toad Sir Henry Hawkins pointed out) but that was par for the course for all who worked at the Bar. Thesiger, Kelly, Wilkins and Cockburn all adopted the same practice as did most men inundated with well-remunerated briefs.

And talking of Alexander Cockburn, a surprising thing happened. In the

Running Rein

case he had been content to make use of his position as senior counsel to fade into the background when the case began to go sour on us, and he had disappeared entirely when the brickbats began to be thrown from the Bench. I was the one who stood up to be bloodied, though in fact the injuries turned out to be superficial in that the diatribes hurled by Baron Alderson actually resulted in an increase of business for me, not least among the racing fraternity, which included,

naturally

, most of the aristocracy at the time. And, perhaps because I stuck it out manfully, endured the strictures of the Benchers of the Inner Temple and made no complaint, Cockburn’s attitude changed towards me. It was in fact he who made the first move, one evening when our paths crossed at the gambling tables in The Casino. He invited me to share a bottle with him; we fell to discussing various matters regarding women, horses and prize fights and the upshot of it was that he invited me back to his chambers where we

maintained a convivial conversation over several bottles of port well into the early hours of the morning.

In other words, a sort of friendship arose between us. We shared interests in common. He enjoyed card-playing as a pastime, and he had scrambled out of enough West Country windows in his youth, in avoidance of angry husbands, to be amused by my own

predilections

in that respect. Mind you, he had a better figure for that kind of escapade: he was far slimmer than my own portly self.

I have no doubt that he was, to some extent, responsible for my easy acceptance into the higher ranges of Society also: the fact he was a companion of mine from time to time at the night houses was noted by the gentry who frequented these locations, and my name began to appear much more frequently alongside his on the guest lists at fashionable houses in Norfolk, Sussex, Yorkshire and even Scotland. I would not go so far as to say that Cockburn and I became boon companions, but during that period we enjoyed each other’s company, and this was duly noted among people who mattered.

It was an expensive business, of course, moving into the world of bankers and politicians, aristocrats, admirals and major generals, but the briefs were coming in and I found myself rushing between Exchequer and Old Bailey and Common Pleas, travelling by coach over rutted roads to the Assize Courts on the Home Circuit and acting as junior to some of the more prominent Queen’s Counsel in the land. Expensive, yes, but the curious fact was that although that underworld villain, Lewis Goodman, held so much of my paper, and my financial indebtedness to him grew ever larger each year, he made few attempts to dun me … in fact, he made none. From time to time he would cancel a debt due, or extend the time limit on a bill for no apparent reason, although there were other

occasions

when he made use of that indebtedness to put some pressure upon me.

I recall, for instance, that he approached me one night when I

was at the tables at one of the night houses he owned in Regent Street. I was reluctant to recognize him, but he stood beside me, tall, elegant, immaculately attired, gravely observing the play for a little while before turning to me and murmuring softly, ‘A word, if I may, Mr James?’

I hesitated, reluctant to be observed in his company, but it was an opportune moment to leave the table for I was losing heavily, as usual, so after a moment’s delay I followed his slim form towards a far corner of the crowded room. A table stood there, empty apart from a bottle of claret and two glasses. Goodman flicked up his coat tails, seated himself and gestured to the vacant seat beside him. I glanced around: the bulky form of Porky Clark hovered nearby. The scar-faced ex-pugilist was never far from his master, like a protective bulldog. I took the proffered seat reluctantly, as Lewis Goodman poured two glasses of claret, his lean, delicate fingers almost caressing the glasses.

‘To your continuing professional health, Mr James,’ he murmured, raising his glass.

It was a toast I could hardly refuse since so much depended on it.

‘It seems you are doing very well these days,’ Goodman continued, his gleaming eyes fixed on me and a slight smile playing on his sensuous lips. ‘I follow the law reports in the newspapers with much interest in view of your forensic exploits.’

I made no reply, still unhappy at the thought of being observed in the company of such a notorious villain.

‘And the Society papers too,’ he added. ‘Fashionable houses, balls, the attention of high-born ladies of light temperament, no doubt …’

‘What do you want, Goodman?’ I demanded irritably. ‘I’m aware there are some bills falling due next week, but I assure you—’

He chuckled. He raised a hand, and I caught the glint of gold at his wrist. He was always expensively dressed, this prominent

member of the flash mob, and was known for his propensity to sport considerable jewellery about his person: gold wristbands, diamond tiepins, ruby rings on his left hand. I always considered it pretentious, and low, to demonstrate his wealth in such an obvious manner. ‘Please, Mr James, let’s not consider the question of the bills falling due. I’m aware that a gentleman of your standing, and future prospects, must lay out a considerable amount of tin to further his career. Holding your paper is, as you are well aware, a sort of insurance for me, rather than a way of becoming rich. And, I’m sure you’ll agree, I’ve been of an obliging nature in the matter of timely repayment.’

I knew what he meant by insurance, recalling the murder that had followed the

Running Rein

affair. Reluctantly, I nodded

agreement

, and sipped the claret he had provided. It was of an excellent vintage, but that did not surprise me. Lewis Goodman was known to live well.