Daily Life During The Reformation (13 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Drinking and dancing in public houses at feasts or in

private homes was the highlight of entertainment for the Germans. In addition,

they had shooting contests with crossbow and harquebus, sleigh-riding through

the streets when snow covered the ground, and hunting and hawking, although the

latter was generally off limits to all but the princes. At the time, there were

still bears, wild oxen, wolves, wild boar, and rabbits in Germany. The princes all

had herds of red deer and harts freely roaming their forests that were a curse

to the peasants as the animals ate their crops and trampled their fields.

During harvest time, the country people stayed up all night to try and scare

away the animals (especially the red deer) from their wheat fields and

vineyards by whistling and making loud noises, but the animals learned that

they could not be harmed and seldom moved away. To kill a landowner’s deer,

boar, or a wild goat could lead to either execution or having one’s eyes put

out. Wolves, it seems, were fair game for all.

Moryson observed at first that in spite of religious

differences, the German Protestants were surprisingly tolerant of each other;

but he was not aware of the animosity that lurked beneath the surface of public

life. Eventually, however, he arrived at the conclusion that Calvinists and

Lutherans hated each other with a passion.

NURNBERG

Nurnberg, in the state of Bavaria, was indicative of urban

living in many German towns. The merchants of the city were frugal in business

and lifestyle, and some were very rich. Like other townsmen, they took care of

their civic duties such as standing guard on the walls at night and received no

special treatment in the taxes they owed or if they broke the law.

The city stood in a good location for trading purposes. In

1450, a census revealed about 30,000 inhabitants, and another, in 1622, showed

a population increase to some 40,000–50,000, of which more than half were

artisans. Nurnberg became a focus of the German Renaissance during the

fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and was also an early center of humanism,

science, and printing. In 1534, it was the first of the imperial cities to

embrace Protestantism.

The free imperial cities tried to control the number of

people low on the economic scale by setting a fee for citizenship. Nurnberg set

this at 100 gulden, which was high and more than many other free cities

charged. Also required was a minimal amount of property. A dye master wishing

to establish a shop in town with rights of citizenship, for example, needed 350

gulden: 200 gulden in property, 100 to become a citizen, and 50 for a craft

license. It was not the same for all crafts. A linen worker needed only 50

gulden in property. Such cities were also home to a large class of noncitizens

such as piece workers in cloth industries, day laborers, and assistants to

artisans and merchants—many of whom were transient and lived a day-to-day

existence.

Everyone had their rank within society, and all were

expected to behave accordingly. In the cities, people lived on certain streets

depending on their work or profession, and their mode of dress would be

appropriate to their class. The manner of clothing was set out in sumptuary

laws, as was the way in which houses could be decorated.

Among the artists who were born or lived there, the painter

and printmaker Albrecht Durer was the most prominent and well esteemed by his

contemporaries. Others, such as sculptors, painters, and woodcarvers, adorned

the city with their works, which brought together the Italian Renaissance and

the German Gothic traditions. Scholars went to Nurnberg to lecture, and a

printing press was established there. The first pocket watches, known as

Nurnberg eggs, were made there around 1500. An interest in culture on the part

of the prosperous artisan class found expression in the contests of the master

singers, among whom the shoemaker-poet Hans Sachs was the most well known.

Foreigners such as William Smith of London who resided in

the city from the 1570s to the 1590s lauded its virtues and presented some

aspects of life in letters back to England. He mentioned the liveliness of the

city and remarked on the clothes, the government, festivals, and morals.

Smith recorded that the city was well painted, and gutters

and spouts for rain water were of copper, gilded, and fashioned like flying

dragons. The buildings were high and stately but only up to four storeys. They

commonly had three or four garrets, one above the other,—in which the wealthy

stored their grain. Few houses were made completely of timber; lower storeys

were generally of stone.

After Augsburg and Koln, Nurnberg was one of the most

populous cities of Germany, but as in most major towns, there was a wide

disparity of wealth. Smith was impressed with the good order and cleanliness

and that many lanes were paved. The city was well provided with public hot

water baths and wells that served most of the houses. He also stated that no

dunghills existed along the streets but were found only in odd corners, and

that people did not urinate in the streets. Refuse could not be thrown out of

the house until after ten o’clock at night under penalties of fines or

imprisonment.

Each family was allowed to keep one pig that had to be

housed outside the city when it became six months old.

Since not all cities had such stringent laws as Nurnberg,

some merchants found it behooved them to relocate to other places such as

Augsburg where mercantile supervision was less onerous, and laws were not

enforced so scrupulously.

In crowded environments, disease was always at hand to

strike down the vulnerable. Between 1560 and 1585, major epidemics racked the

city. First came plague, then smallpox, then plague again and dysentery,

followed by measles and, once more, smallpox. The latter took 5,000 lives in

the year 1585. Most victims were children. The city suffered a population

decline that took years to recover.

There were many towers. Smith figured about 200, each with

lodging for watchmen. The streets were patrolled every night by a man who blew

a horn at the foot of each tower to make certain the watchman was not sleeping.

If the blast of the horn was not acknowledged, then the watchman had to be

asleep, and subject to eight days in prison on bread and water.

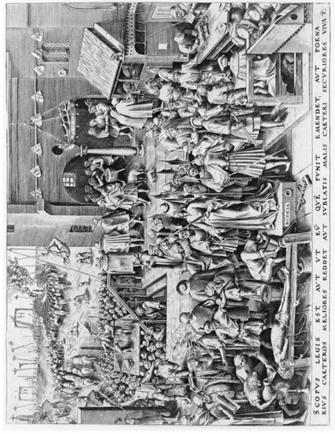

Pieter Brueghel’s

Justicia

.

Justice stands blindfolded as people around her are being tortured.

Crime

and Punishment

Criminals or suspected criminals received little in the way

of justice. They were generally allowed to say something on their own behalf,

and this would be followed by close questioning from the magistrate. If the

accused did not plead guilty, they were escorted to the torture chamber where

in due course they would confess to anything.

Convicted thieves were beheaded if they were citizens of

the city or hanged if they were not. Hanging was considered by far the worst

punishment since the agony was prolonged.

A conviction of arson brought the perpetrator to the stake

to be burned alive. Anyone who swore a false oath had two joints of their forefingers

amputated, and blasphemers had their tongues cut out. For lesser crimes,

punishment included whippings and banishment from the town.

Trials lacked witnesses and lawyers for the defense, and

judgments were already in place before a hearing. The law required evidence of

guilt, and a confession was extracted by any means available. For serious

crime, execution followed immediately.

The Church generally had no sympathy for the accused. Pain

and suffering were unimportant. Individual clerics who were charged with care

of their souls explained the beliefs of the Church in the hope that their faith

would be renewed and they would die with a prayer on their lips.

City Regulations

Smith, an innkeeper himself, speaks of the hospitality of

the city council. A person arriving in town with two or more horses presented

his name to the magistrates who immediately sent him pots of wine and bid him

welcome. If the guest was a nobleman, he received one wagon laden with wine,

another with oats and a third with foodstuffs. He also found the citizens

honest and as good as their word. If a purse was dropped in the street with

money or other valuables in it, for example, its owner was more than likely to

have it returned. Smith lamented that such was not the case in London.

The city council in Nurnberg, as in other cities, regulated

everything. Nothing was kept secret. The authorities took note of the amounts

spent on weddings, clothes, christenings, feasts, parties, gifts, and funerals.

Draconian details of these and other events were laid out in manuals to be

adhered to by the public. It was forbidden to be secretly betrothed, and if a

man wished to serenade his lady, the payment to the musicians was restricted to

bread, cheese, fruit, and a cup of wine, which could be passed around only

once. For a newly married couple, only one party and seven guests were allowed.

For all sorts of entertainment or ceremonies, there were manuals to be

followed, and any breach of regulations was subject to fines. In addition, a

list of guests had to be sent to the office that dealt with weddings and

funerals. Dancing after a wedding could only continue until ten o’clock. These

are but a few of the many burdensome restrictions placed upon the citizens.

AUGSBURG

The free city of Augsburg, with a population of about

30,000, ranked on a par with Nurnberg and Strassburg. The life of the city was

trade, but monasteries, convents, and parish churches were in abundance. There

was a cathedral, containing relics of saints, towering above the buildings and

its extensive land holding surrounded the city beyond the walls. Its power

rivaled that of the city council. Lodgings for numerous clergy were tucked away

in its shadows, and here, business was good for prostitutes. Market day was

particularly active and noisy with throngs of servant girls bargaining with

stall keepers.

Nearby thieves and swindlers sat dismally in the stocks

having lost all semblance of dignity. When their time was up, they were

banished from the city. The great houses and gardens of the rich merchants

contrasted with the cramped quarters of the workshops and one-room hovels of

the craftsmen.

Martin Luther visited Augsburg in 1518, and from then on

his supporters grew in numbers as did problems for the city council. By

1524–1925, the council, made up of aristocrats, wealthy merchants, and guild

masters, was under threat. Radical evangelical preachers and followers carried

out direct action that included throwing salt into holy water, tearing up

missals, and other annoying deeds. The council ejected one of the instigators,

an evangelical monk, from the city, causing a riot. Many of those who gathered

to protest the expulsion were poor weavers, laborers, and some guildsmen. The

council feared more social unrest from the people who united behind Luther and

took the bold step of secretly executing two weavers. Unsure of its citizens,

the council then stationed armed mercenaries in the city. In Augsburg as

elsewhere, the Reformation took on a social and economic dimension as the poor

resented the wealthy upper class that ran city hall.

By the late 1520s, the evangelist preachers and the

political elite began to form alliances, while radical Lutherans started to

associate with the Anabaptist movement, persecuted by both Lutherans and Catholics.

Throughout the 1530s, propaganda leaflets flooded the city mostly directed at

monks and Catholic priests who were condemned for every imaginable, and

especially sexual, sin.

In 1537, Hans Welser (a disciple of Zwingli) and Mang

Seitz, were elected mayors of the city. The Reformation was now firmly

established. Tensions continued, however, between rich and poor, guildsmen and

aristocrats.

CHANGES IN MANNERS

Some of the old medieval customs became offensive to the

new religious orientation. In Saxony, a newly married couple bathed together

and emerged from the water wet and naked to distribute refreshments to a crowd

of friends. Consummation of the marriage was closely observed by half a dozen

or more people to ascertain that the couple had performed this function

properly, and there could be no dispute about the legality of the marriage.

Such practices began to change about 1550 with the spread of the Reformation as

a more prudish attitude toward nakedness and sex set in. Similarly, defecating

and urinating in public places became taboo.