Daily Life During The Reformation (15 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Towns

A small percentage of people lived in cities such as London

where tradesmen tended to live in the same quarter For example, butchers and

slaughterhouses occupied the same street ca

ll

ed the Shambles.

Sewers or drains were few, dirty water and garbage such as

decaying vegetables and offal was cast into the streets. Rats thrived as did

disease such as smallpox, measles, typhus, scarlet fever, chickenpox, and

diphtheria. Outbreaks of the plague occurred every few decades killing 10 to 20

percent of the inhabitants of any town. Numbers recovered, however, as there

were always poor country people who moved into the cities looking for work.

While everyone was officially required to clean the area in

front of his dwelling at least once weekly, cities were generally dirty,

crowded, and foul-smelling. In London, there were not many public toilets, but

what they had were situated beside streams. In the majority of towns, there

were none, so everyone used any spot that was convenient.

Water came from wells, transported by water carriers who

brought in the heavy containers on their backs. In some towns, pipes or

channels had been put in place to bring it in from the countryside.

Streets, at night dark and dangerous, were narrow, and

upper floors of buildings jutted out, sometimes practically touching those on

the opposite side. Apart from the possibility of being robbed, people had to

face a variety of hazards as they made their way along dark unpaved lanes such

as deep holes in the road, low hanging balconies, or a horseman in a hurry. If someone

were trampled by a horse, the rider would seldom even look back. In London, a

boy could be hired to light the way with a lamp, but most people avoided going

out after dark.

Tudor Homes

By the sixteenth century, houses no longer had to be

defensive. The very wealthy usually had large mansions in the countryside,

employing as many as 150 servants. These homes were built with many chimneys

and fireplaces that were needed to keep the huge rooms reasonably warm and to

prepare the food.

People of more moderate means had solid half-timbered

houses comprising a wooden frame with wickerwork and plaster as fill. Sometimes

they were filled with bricks. Although roofs were usually thatched in the

countryside, in London tiles were used due to the ever-present danger of fire.

Furniture remained basic but for the well to do, oak would

be used in the main since it was expected to last many generations. Chairs were

used more than previously, but they were costly and even in affluent homes,

children and servants commonly sat on stools. Windows of glass, held together

by strips of lead, were also expensive, and anyone who moved to another

residence, would take the windows with them.

The very poor used bands of linen saturated in linseed oil

for windows. Chimneys were totally unaffordable for these people whose houses

usually had a hole in the roof for the smoke from the fire to escape. Most

peasants lived in small huts with floors of hard earth, using benches, stools,

a table, and perhaps a wooden chest as furniture. Their mattresses were packed

with straw or thistledown spread over ropes across a wooden frame.

In contrast, the walls of mansions were paneled with oak in

an effort to avoid drafts, as were four-poster beds hung with curtains.

Wallpaper was sometimes applied and tapestries hung to retain the heat.

Carpets, another luxury item, were usually hung on the walls rather than placed

on the floor that would often be covered with reeds or straw together with

aromatic herbs, normally replaced once a month.

The rich lit their homes with beeswax candles, while other

people utilized malodorous candles made from animal grease. The very poor used

rushes dipped in fat before lighting. Clocks were in evidence in some of the

more opulent houses, although the rich carried pocket watches or pocket

sundials.

Gardens of the wealthy often had a maze for pleasure and

games, hedges of sundry shapes, and fountains decked out with flowers. Poor

people might have a small space beside their houses, used to grow vegetables

and herbs.

In 1596, a flushing lavatory with a cistern was invented by

Sir John Harrington, but the idea was slow to catch on, and most people

continued to use chamber pots or cesspits.

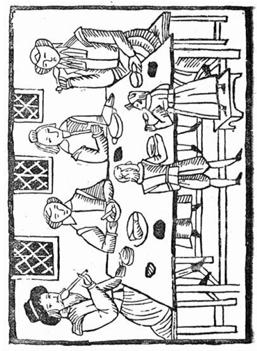

The Family Meal.

Roxburghe

Ballads

. Charles Hindley, ed. (1874) vol. i, 116.

Farmhouses

The farmhouse in Tudor times was usually constructed of

wood and plaster with a thatched roof; although by the end of the sixteenth

century, better-off farmers were building houses of stone or brick with tiled

roofs. The main living room served also as the kitchen and had an open

fireplace with a brick oven beside it. There would be a long table at which the

farmer, his wife, and the servants took their meals together. Sometimes the

children would stand while the adults were seated. Little other furniture was

there except a few benches and a dresser on which were placed the plates and

drinking vessels. Just outside the kitchen door would be a brew house and

dairy. A well and a wood stack would be close by. The barn, stables and tool

sheds stood in the farmyard. Laborers lived in cottages scattered around the

house, and sometimes these consisted of little more than walls, a roof, and a

stone hearth. The smoke exited through unglazed windows and the door. Pigs and

chickens wandered in and out. Each cottage would have a small plot to grow

vegetables.

In August and September, grain was harvested, and threshing

began in the barn with flails, usually short clubs attached by rope to long

staves that separated to beat the stalks. The grain was cleaned and winnowed in

the breeze on a flat pan-like basket to carry off the chaff. (A goose wing

could be used as a fan to create a breeze.) Next came plowing the land that had

been left fallow or that was covered in stubble from the previous harvest. This

was also the time to collect acorns for the pigs, beechnuts, and honey from the

beehives and for gathering in the fruit. November was the time to slaughter

some of the animals, both for salted meat to carry the family through the

winter months, and since there was not enough hay to feed them all.

After Christmas plowing began again, newborn animals were

anticipated, and the crop was sown. Pruning, mending hedges and fences, carting

manure to the fields, and many other chores kept everyone busy. By March, the

barley was sown and children would be sent into the fields with slings to scare

off birds that gathered for the easy pickings.

The housewife tended the herb garden, oversaw the sowing of

flax and hemp, and worked the dairy making butter and cheese using milk from both

cows and ewes. In June, sheep shearing was underway, in July, hay for the

animals was collected, and August was devoted to the harvesting of grain. At

this time, the farmer hired reapers who were paid sixpence a day (plus meals or

a shilling a day without). When the work was finished, the poor were allowed

into the fields to carry away anything they could find that had been left over

from the harvest.

Social Classes

Vast amounts of land were owned by the nobility in this

highly structured society. Below them were the gentry and the wealthy

merchants, also landowners who like the nobility, were usually educated and

unwilling to perform undignified manual labor. Further down the scale were the

yeomen who owned their land and were sometimes well off financially, but who

had no issues about working together with the farmhands. At this level, too,

were the craftsmen who made the items necessary for everyday living such as

shoes, tools, and clothes. Generally, both yeomen and craftsmen were literate.

Tenant farmers, on the next rung of the social ladder,

leased their land from the well-to-do owners and struggled to make a living and

feed their families.

At the bottom were the wage laborers, generally illiterate,

who walked a fine line between work and mendicancy. They made up over 50

percent of the population, living at subsistence level with little food,

shelter, or enough clothes to keep warm. A rising population meant a shortage

of work, leading to many unemployed.

It was possible to move up a social notch or two: an

ambitious wage earner with intelligence who was willing to persevere, could

become a yeoman if he had enough money to purchase a coat of arms and call

himself a gentleman.

The

Poor and the Destitute

About a third of the population lived in poverty, but Tudor

law, while tolerating cripples, was harsh on able-bodied beggars deemed

vagabonds, unable to find work at home, and who left their parishes in order to

find it elsewhere.

There had been laws against such transients for a hundred

years, but in 1530, the old and infirm poor were issued with licenses to beg. A

jobless man roaming the streets without a license could be taken to the nearest

market place, tied to a cart, and whipped before being ordered to return to his

parish. In 1536, another law was passed subjecting vagabonds to a whipping for

the first offense and part of their right ear to be sliced off for a second,

with a view to easy identification. A third offence led to the gallows. This

was again modified in 1547, to condemn anybody found loitering for three days

to work for anyone who would hire him for whatever wages offered. If no one

took him on for a wage, then he had to work for food and drink alone. If he

refused, then he could be sent before the local magistrate and ordered to become

that benefactor’s slave for two years. If he tried to escape, he would be made

a slave for life and branded. This law was abolished in 1550, when flogging was

again made the penalty for nomadism.

A severe vagrancy law was once again imposed in 1572, whereby

for a first offense, the beggar was whipped and branded on the right ear. In

the case of a second offense, he would be executed by hanging. The punishment

in both cases could be commuted if someone employed him. However, for a third

offense, he would be hanged regardless.

In 1576, new laws were passed concerning the old and

disabled that ordered parishes to put them to work in their own homes by

supplying them with materials such as flax, hemp, and wool. Those who resisted

were sent off to a correction center where life was often brutal.

Four years later, parliament passed the poor law whereby

every parish was commanded to put up a workhouse for these people. There, they

were forced to work to their fullest ability. The original purpose of the

workhouse was to remove such people from the urban scene. Inmates could be let

out to work if it were available, but they were confined when it was not. The

death penalty for vagrancy was finally abolished in 1597.

The Anglican Church

In England, the Reformation followed a different course

than elsewhere in Europe. The changes within the English Church proceeded at a

slower pace as reformers oscillated between the wish to continue the Catholic

traditions and the desire to take up the new Protestantism. The result was

compromise.

England had already undergone anticlerical movements in the

fourteenth century that had given rise to the Lollards and John Wycliffe who

had translated the Bible. However, anyone found with a Bible in English was

considered a heretic and burned at the stake.

The Reformation in England took on a different character as

it was initiated by Henry VIII’s desire to divorce his queen, Katherine of

Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn, which the pope would not permit. As a

result, in 1534, Henry cut off his ties with the Holy See making himself

Supreme Head of the Church of England by the Act of Supremacy. Between 1535 and

1540, the policy of the dissolution of the monasteries led to attacks on Church

land and property, which were taken over by the crown and the nobility.

Henry died in 1547 and was succeeded by his son, Edward VI,

who was nine years old at his coronation (and only sixteen at his death). Under

his rule, the reform of the Church of England was established officially.

Mary, daughter of Katherine and Henry, a fierce Catholic,

reigned next, from 1553–1558 and immediately began the restoration of the

Catholic faith. She promoted the return of property such as furniture taken

from the Church during the dissolution of the monasteries, but permitted the

nobles to retain the lands they had acquired. During Mary’s sovereignty, some

300 Protestants, including about 56 women, were burned in the Marian

persecutions, their holdings given over to the state; but instead of being

discouraged by the number of martyrs, the Protestants became more avid than

ever in their hatred of their monarch who by then was known as “Bloody Mary.”