Daily Life During The Reformation (31 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Their word reflected their honor; however, and the act of

spitting and shaking hands meant any agreement would not lightly be broken.

Reivers usually wore light armor or a ‘jack,’ a quilted

leather coat with plates of metal or horn sewn into it, along with helmets of

metal. They were sometimes called the “steel bonnets”. They used lances

(sometimes as long as 13 ft), shields, and on occasion longbows or small

crossbows. They always bore a sword and a dagger; and later in the century,

they carried arquebuses and pistols.

Finnish Light Cavalry

Hackapells were light cavalryman whose name comes from the

Finnish war cry

hakkaa paalle

, most commonly translated, "Cut them

down!” These troops were fast, their horses strong, and their attacks were

ferocious in spite of the fact that they only carried two pistols and a sword.

Hackapells were used by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

during the Thirty Years’ War and in small regiments by German city states.

Tactics and Weapons

The use of pike men was the first major threat to the

armored knights of the Middle Ages; and from the beginning of the sixteenth

century, they were often used alongside men of the infantry who were armed with

crossbows, longbows, or muskets.

At the same time as firearms (muskets and hand guns) took

the place of pikes and bows, military units became more effective as the front

ranks of soldiers fired and then kneeled or stepped back to reload, while the

next rank fired their weapons. Although the effective range of firearms was

only about 100 yards, this technique created a continuous and deadly field of

fire in front of the formation. The infantryman, however, was highly vulnerable

to cannon shot containing steel balls, bits of rock and metal, nails, and other

lethal substances. Cannons could demolish city walls, changing the nature of

siege warfare.

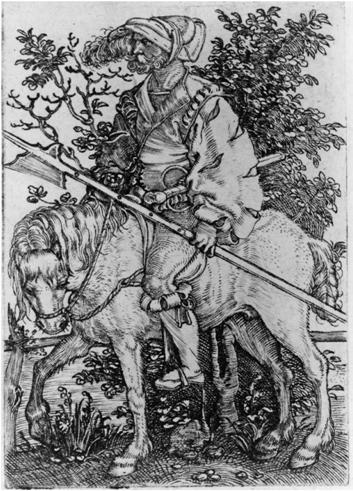

Halberdier on horseback.

Engraving by Barthel Beham, 1500–1540.

Ensign, Drummer, and Piper.

Engraving by Hans Sebald Beham, 1543.

MILITARY MEDICINE

Wounds suffered by the soldiers also changed along with the

weaponry, and many more injuries to the limbs occurred. Wounds from traditional

weapons such as pikes and swords, in general tended to be relatively clean, so

the odds of recovery were fairly good. Compound fractures, once rarely found in

battle conditions, were now commonplace due to the force of a bullet striking a

bone. Unsanitary conditions and surgeons probing gunshot wounds with unclean

fingers usually led to infection and death. The shattering of bones resulted in

the need for amputation, which often resulted in death from shock.

Many other soldiers succumbed to dysentery, typhus,

smallpox, malaria, plague, syphilis, and trench foot whereby they lost part of

the rotted foot or toes as they took off their boots for the first time in

months. In addition, constant heavy shelling led to what might be called today

traumatic stress disorders.

In times of war, civilian physicians and barber surgeons

were often forced into the army for the duration of a campaign in order to

treat the enlisted men. The barber surgeons were trained through apprenticeship

and experience to perform surgical and other military medical tasks.

Medical manuals were published in the sixteenth century and

used by the doctors and barber surgeons. With the printing press, knowledge became

more widespread, having the effect of standardizing procedures since medical

personnel all over Europe could now consult the same references and deal with

the terrible wounds.

In spite of advances in medical knowledge in the

seventeenth century, treatment of disease and infection progressed slowly. One

of the main problems was the lack of a scientific method to research

medications. Many remedies were tried to help patients; but more often than not,

they proved to be useless, causing more harm. Apothecaries frequently sold

salves and powders that had no benefit whatsoever.

The French military surgeon Ambroise Pare´ was responsible

for major advances in the treatment of wounds incurred on the battlefield.

Previously, it had been thought that since the patient often died of infection,

the lead in the bullets poisoned the wounds. Pare´ tried a new treatment and

instead of cauterization when he ran out of oil one day while treating gunshot

wounds, he concocted a dressing made of raw egg whites, oil of roses, and

turpentine which, he discovered reduced infection, gave the patient some relief

from pain and speeded up recovery when applied.

Infection was also the result of burns from exploding

cannons and muskets. In 1537 during the Turin campaign in Italy, a boy fell

into a caldron of boiling oil. En route to treat him, Pare´ stopped to obtain

medicines from an apothecary. There, an old woman told him to use a dressing of

crushed onions and salt, which she said would reduce the blistering and

scarring. When Pare´ came to treat the boy, he followed her advice by putting

onion paste over some of the burnt flesh, while using the traditional remedy to

treat the rest of the wound. The next day he discovered that the part treated

with the onion paste was free of blisters, unlike the rest that was covered in

them.

Pare´ also introduced better methods of battlefield

amputation using ligatures that reduced the chances of heavy bleeding. It was

learned about this time that this helped to prevent gangrene.

Another innovative pioneer of battlefield medicine was

William Clowes, a barber surgeon who served under the Earl of Leicester in the

Netherlands in 1580. He became an expert in treating battle wounds claiming

that many deaths in battle or afterwards were caused by the incompetence of the

surgeon. Low pay and possible danger kept many of the best surgeons away from

military duty.

Hygiene and Hospitals

Military field hospitals for wounded soldiers were first

established in Spain under Queen Isabella during the conquest of Granada in the

last decade of the fifteenth century. Six large tents equipped with medicine,

bandages, and beds were moved from siege to siege as Muslim cities fell one by

one. The queen also converted a royal building in Sevilla into a hospital for

incapacitated soldiers who had served the crown.

Disease could spread easily throughout army camps; but some

commanders tried to do something to avoid it. The Earl of Leicester, for

example, when in the Netherlands, insisted upon places being set up for

soldiers to relieve themselves. He also designated specific places outside the

garrison where animals were to be butchered and their entrails to be buried. On

pain of death, the stream beside the camp was not to be polluted.

Those commanders who were not strict on hygiene often

suffered the consequences of epidemics, and the Spanish and other initiatives

were not employed by other countries even when they were known about. The

government of Elizabeth I, for example, ignored proposals by Thomas Digges, an

English astronomer, to create a pool of carriages and drivers for ambulance

services in war time.

The first military hospital outside of Spain was

established by the Spanish duke of Alba in the Netherlands in 1567 where combat

wounds, disease, and battle trauma were cared for and supported by the Spanish

government. During the early seventeenth century, more hospitals for wounded

soldiers were beginning to appear. In 1638 the Swedish government used a former

monastery for such treatment. During sieges, makeshift field hospitals came

into existence in other parts of Europe that were generally respected by both

sides of a conflict.

Ambroise Pare operating on a

soldier wounded in battle.

SIEGE WARFARE

Feudal castles or medieval town walls could be knocked down

fairly easily by cannon, but as military engineers quickly replaced high walls with

thick, squat, star-shaped fortifications with bastions, cannon were less

effective.

Since towns were of economic importance, sieges became a

major strategy. This required larger armies since the besieging force had to

surround a town and fortify their own camps in order to protect themselves

against attacks from the rear.

Soldiers occupied in warfare often spent weeks or months

encamped outside a town’s walls, and many died from disease brought on by

malnutrition and lack of supplies when the local area had been stripped of

food.

COSTS OF WAR

Paying for ever-larger armies taxed the treasuries of

states engaged in warfare. Some wars were settled more by financial pressure

than by actual military means. It was not uncommon for a victory to melt away

because the army disbanded afterwards for lack of pay. The need to continue a

war and occupy enemy ground often led to a rise in taxes and various schemes

for obtaining steady income for the royal treasury. In France, this often meant

the creation of more government bureaucracy by selling administrative and

judicial offices to the highest bidder. Competence was not a necessary factor.

The unpopularity of Henri III’s regime was primarily caused by his need to

raise money to finance wars that were entering their third decade.

Apart from the guard that traveled with the court,

permanent garrisons were posted around the more troublesome borders between the

Valois kingdom and Habsburg territories (the north and east). Not only did the

citizens pay higher taxes to support armies from which they reaped no real

benefits, but they saw their sons go off to war often never to be seen again or

to return maimed and incapable of work. A terrible price for a farmer was to

see a needed son go into the army.

Soldiers were expected to live off the land; and campaigns

generally took place between March and October when the weather was better, and

the land was more bountiful. Some communities set up warning systems of armies

on the move, so they could abandon their farms and hamlets and make for the

nearest fortified town. Such measures took a toll on farm production especially

during planting or harvest time.

The little pay soldiers received was unreliable. They

seized what they needed from peasants or conquered towns. Pay could be months

and even a year in arrears. Lack of money helped account for high desertion

rates, often rebellion among the troops, and intense sacking of the local

environment. Foraging parties stole anything movable. For most common soldiers,

army life was not glorious but miserable. Sometimes systematic destruction of a

given area, including towns and villages, was ordered to prevent enemy use when

troops were withdrawn. Agricultural production might be lost for years. When

pay did arrive at the front, the money lenders who had advanced cash to the

soldiers, swooped down to collect their payments at outrageous interest rates. Officers,

too, participated in these usurious practices.