Daily Life During The Reformation (9 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

It has been asserted that the English did not harm ravens

because they believed that the legendary King Arthur had been transformed into

one, and his return was awaited by the people. This belief, in fact, continued

in Wales and Cornwall until almost the end of the nineteenth century.

In 1662, a Scottish woman, Isobel Gowdie, when confessing

to witchcraft, said that crows were a favorite form for witches to take when

traveling at night. The Brothers Grimm, in their collection of German legends,

reported that a man and woman from Luttich were executed in 1610 for traveling

about in the form of wolves while their son accompanied them as a raven.

Cats, especially black ones, have always been a target of

superstition and cruelty and associated with witchcraft and magic. To come

across one at night signified the devil or a witch was nearby. It was believed

that witches transformed themselves into cats in order to cast spells. They

assembled at night and howled, copulated, and fought under the direction of a

huge tomcat thought to be the devil himself. For protection against a cat’s

evil powers, one had to maim it such as breaking its legs. A maimed feline could

not attend the Sabbat or cast spells.

Every year, cats were killed by the thousands in France

into the seventeenth century.

Beliefs related to cats varied from place to place. In

Brittany, if a cat crossed the path of a fisherman, his catch was doomed. In

Anjou, the bread would not rise if a cat entered a bakery.

These animals also figured into folk medicine. To suck the

blood from a freshly amputated tomcat’s tail would help cure bodily wounds

incurred by a fall. For pneumonia, it was beneficial to drink the blood from a

cat’s ear mixed with wine.

Cats were victims in other ways. In London during the

Reformation, a Protestant crowd shaved a cat to resemble a priest after which

they dressed it in priestly vestments, and then hanged it on the gallows at Cheapside.

MINERS AND GHOSTS

Like almost everyone else, miners’ lives were replete with

superstition and magical stories. They were afraid of spirits who lived in the

dark shafts, and tales were abundant of unattached hands carrying candles,

strange voices in the dark warning of cave-ins, and ghostly black dogs

indicating disaster was imminent. Underground, in the flickering candle light,

shadowy apparitions could easily play on the imagination of people raised on

such beliefs.

THE PEASANTS OF LORRAINE

Workers on isolated farms out in the countryside were

particularly prone to terrors of the night in the form of supernatural beings

as well as from ordinary brigands.

In Lorraine, in eastern France, an area lying astride

important crossroads between France and Germany, the people suffered, perhaps

more than most from invading armies, battles, pillage, devastation, and robber

bands of unemployed soldiers. Afflicted by poverty and starvation, they were

also terrorized by their belief in sorcery and evil demons. In addition, they

lived in fear of the Catholic Inquisition whose severe judges were determined

at any cost to root out the causes of evil perpetrated by the devil. Anyone

could be tortured if denounced as a participant in satanic rites.

A magistrate in the town of Nancy, charged with clearing

evil-doers out of the region, boasted to the Cardinal of Lorraine that he had

sent 800 sorcerers to the stake to be burned. Arrogantly, he claimed that his

justice was so effective that 16 people had killed themselves rather than face

him.

In 1602 a judge, M. Boguet, commissioned to destroy nests

of devils said to be in the Jura mountains, repudiated the use of torture to

which he believed the true disciples of the devil would be immune. He studied

carefully the rites of the Sabbat and came to the conclusion that in the Jura,

the devil himself appeared as an enormous black sheep, a candle between his

horns, to preside over the orgies. The sorcerers approached one by one and lit

their candle that burst into long bluish flames. They knelt down and kissed

Satan’s

derriere

. Then came the time of public

confession when the sorcerers told the prince of the underworld of their

exploits since their last meeting together. Those who caused the most wicked

abominations such as having people and their livestock die, the most illnesses,

or the most fruit spoiled were the ones most favored by Satan.

Boguet was greatly struck by the frenetic dances that

sometimes caused women to abort as well as tales that the old men were the most

agile. The judge spared the accused from torture and took care to soften the

inevitable death penalty by recommending that they be strangled before the

flames engulfed them. This judge’s book on sorcery (

Discours des Sorciers

) was studied by many and became

a manual for members of parliament. He decimated the population of the Jura,

and if his own death had not intervened, he may have exterminated the entire

region.

5 - SPREAD OF THE REFORMATION

Religious

reformers made rapid strides in the imperial lands of the Holy Roman Empire,

where the territorial secular rulers were often inclined toward the new

religious point of view as were some members of the Catholic clergy. Reformist

leaders used all means available to condemn and ridicule the Catholic Church

and inform a mostly illiterate society of their beliefs. Besides the printing

presses, woodcuts, engravings, songs, satire, drama, and the pulpit were all

means to instruct the masses.

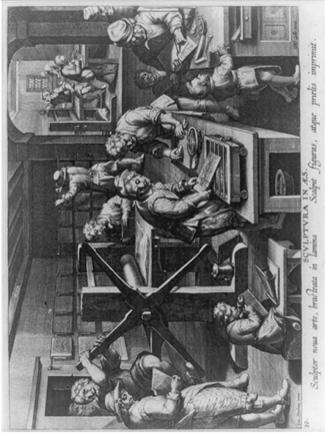

Interior view of a workshop with

men and boys engaged in various activities in etching, engraving, and printing.

GERMANY

How the religious lives and practices of the people were

disrupted by the anxiety, passion, and upheavals of the time is well

illustrated in the case of Germany.

Local congregations, anxious to hear the new orthodoxy,

pressured their village and town councilors to hire a preacher sympathetic to

the Reformation. Unsympathetic city officials found themselves confronted by an

angry populace.

When no church was available to itinerant evangelists, as was

often the case, they preached in the market place, the churchyard, or wherever

there was a willing audience. Church services were now changing; in some cases,

the preacher allowed questions from the congregation during the sermon.

Elsewhere, clerical garb was not worn. In one case the preacher wore a long red

coat, fashionable shoes, and a Scottish red beret.

In some instances, congregations became unruly; in

Regensburg, a Catholic preacher was heckled during the sermon. In 1524, in Ulm,

a priest who began his sermon with a prayer to the Virgin Mary, was driven out

of the church with vociferous abuse.

Where reforms were accepted by the populace, a once-passive

congregation sometimes turned into an unrestrained shouting match. Disputes

with priests reached the point where town councils forbade public contradiction

of preachers, and city officials everywhere reimposed discipline by prohibiting

anyone from speaking during the Mass.

Even in private homes, evangelical sermons were given, and

peoples’ lives were filled with debating religious issues—the most popular

place being at inns but also at spinning bees, Church ales, on the job site, as

well as in the village square where pamphlets were distributed and read out

loud to any gathering. The dinner table, too, always provided a setting for

conversation on religious topics.

Songs and poems scornful of the orthodox clergy were widely

circulated. Some towns prohibited such activity that could lead to public disorder.

There were cases where crowds of Lutherans would invade a Catholic church and

by singing loudly, attempt to drown out the church music.

Tempers flared in Magdeburg in 1524 when a weaver who sang

Lutheran hymns was imprisoned. Two hundred citizens marched on city hall to

demand his release. A number of German cities passed censorship laws

threatening authors and publishers with fines and imprisonment, forcing their

activities underground.

Hans Haberlin, a lay preacher from the village of

Wiggensbach, was detained in 1526 for unauthorized preaching. At the time of

his arrest he was speaking to a crowd of about eight hundred peasants gathered

in a field. In spite of setbacks and opposition, the Reformation spread

throughout the Holy Roman Empire finding fertile ground in many regions.

THE PROTESTANT MOVEMENT IN SWITZERLAND

The religious movement in Switzerland started under Ulrich

Zwingli, a priest. The Swiss confederation of the time was made up of 13 nearly

autonomous states (or cantons) along with some affiliated states. In Germany

and Switzerland, there was at first agreement on reformist issues, but the

relative independence of the cantons brought on conflicts during the

Reformation when the various regions supported different aspects of doctrine.

Some followers of Zwingli, for example, believing the Reformation too

conservative, moved independently toward more radical ideas.

The movement first spread to the major German speaking

cities such as Zurich, Basel, and Bern, but large numbers of people lived in

villages or hamlets tucked away in the high mountain valleys. These places were

snowbound in winter and the locals had to be self-reliant. Some were reached

only by paths leading ever upward hewn out of the sides of mountains with

precipitous drops to river gorges far below. Vertiginous bridges of stone and

wood crossed over deep abysses 1,000-feet below. The hamlet might consist of a

dozen log houses in a clearing surrounded by dark pine forests where bears

still lurked in the sixteenth century and could be a danger. Snowcapped

mountains loomed all around. Compared to the lowland cities with their

pollution, thieves, noise, periodic plague, and civil regulations, people of

the hamlets lived a serene life in the fresh air with room to expand. They

raised chickens, geese, sheep, goats, and cows; grew vegetables in the short

summer; and pretty much lived by their own resources. Milk, often made into a

soup and cheese were the primary staples. There was no shortage of wood for

fires and warmth and in winter close to the fire on a straw mattress was the best

place to sleep. Most of the mountain peasants were poor, but some with more livestock

and a little money would send their children for some schooling in the valley

towns.

Young children occupied themselves with homemade toys in

the form of puppets, toy soldiers and horses, dolls, throwing rocks at a

target, racing and pole-vaulting, When boys were a little older, perhaps as

young as eight, they became shepherds and took the livestock up higher into the

mountains to the summer pastures. This too was a dangerous life. Shepherds

sometimes became lost when enveloped by dense clouds and fog. Sometimes, bears

after the livestock menaced the guardian, falling rocks and avalanches were

always a threat, a sudden unexpected snow storm could bury the shepherd, and food

and water could run out days away from the hamlet. Sleeping on straw mattresses

teeming with lice and fleas was uncomfortable enough, but if the lice carried

typhus, the shepherd’s life was in danger. Usually barefooted and with little

more than a tunic, the boys from impoverished families had little choice but to

follow in the path of their fathers. There were, of course, some young men who

preferred not to tend sheep and goats in the highlands and left the villages

and hamlets for opportunities in the cities and took their chances on survival.

When work was nowhere to be found, they resorted to stealing chickens and

geese, onions or carrots in the fields, and begging in the streets.

Mountain people were not entirely isolated and would sell

their wool and cheese in the larger villages when weather permitted the journey

into the valleys below, and there they could barter for flour, wine, and

luxuries such as pepper or spices imported from clearing houses in Amsterdam

and brought to the cities and towns of Switzerland by mule carts.

News of the reform movement gradually reached the villages

and hamlets by traders, visiting friends, or relatives. There was generally

some visitor who could read and brought Protestant pamphlets to the outlying

communities.